The following Five governing Principles of the CoG are outlined below and described in some detail at this link.

Principles

The five principles of the Continuity of Government Program were as follows:

1. Protection of key government elements to ensure continuity of a recognized and duly constituted governmental authority.

2. Government had to be able to operate on a decentralized basis with Central, Regional and Zonal elements.

3. Governments located in areas with risk for direct attack had to be relocated to safer areas and be provided with fallout protection.

Those governments located in areas where the principal risk was radioactive fallout only had to be provided with fallout protected accommodation.

4. Lines of succession for senior elected officials and selected government officials had to be established.

5. Essential government records required for survival and recovery were to be identified and made accessible to wartime governments.

CoG Origins

- By the mid 1950s a massive nuclear attack on North America was becoming a very real possibility.

- Escalating political and military tensions between the Western NATO nations (headed by the United States) and the Eastern European Warsaw Pact nations (directed by the Soviet Union) were becoming increasingly threatening. Both sides were building nuclear and conventional warfare arsenals at an alarming rate.

- This situation motivated the Diefenbaker government to announce in the House of Commons (May 1958), a wide range of civil defence measures to respond to the increased threat. One of these measures was the creation of the Continuity of Government (CoG) Program.

- The CoG called for the establishment of a dispersed system of protected emergency government HQ facilities capable of sheltering small numbers of elected representatives and selected supporting staff from the direct effects of a nuclear attack. Federal and provincial officials assigned to these ‘bunkers’ were intended to provide (what was recognised to be only a ‘thin thread’ of) continuity of legitimate government in order to avoid complete anarchy in the horrific aftermath of a massive exchange of nuclear weapons.

Prime Minister Diefenbaker:

(statement to the House of Commons – August 21, 1958)

“…Considering the possibility that there would be little or no warning of attack and having regard to the vulnerability of our communication and transportation facilities, the normal peacetime arrangements for government would be inadequate in the event of a major war. There is therefore a need, in our opinion, for the development of a decentralized federal system of emergency government with central, regional and some zonal elements. We intend to provide for a suitable central authority and to establish provincial, regional and zonal organizations through which a large amount of the work of the federal government could be carried on in time of war by the necessary delegation of authority to federal officers.”

“There is therefore a need, in our opinion, for the development of a decentralized federal system of emergency government with central, regional and some zonal elements. We intend to provide for a suitable central authority and to establish provincial, regional and zonal organizations through which a large amount of the work of the federal government could be carried on in time of war by the necessary delegation of authority to federal officers. We recognize, of course, that the assistance and co-operation of provincial and municipal governments will be necessary in the development of the regional and zonal organizations, and I expect very shortly to approach the provincial authorities and provincial governments in this connection”

The Leader of the Opposition Mr. Pearson: (in response)

“The Prime Minister has introduced into the quiet atmosphere of this committee a matter ofCwhat shall I call it almost cosmic importance. He has faced us with a problem unprecedented in the sense that we have never had to face it before, and unprecedented also in the horrible possibilities involved in it. It is well, I think, that he should have done this in order that we may in this house and in the country be aware of the realities of the situation which faces us at the present time. He has not only indicated the necessity of planning against this horrible eventuality, but he has also indicated that such planning is taking place.”

Continuity of Government Program 1958 – 1992 Summary and in more detail at this link.

In the mid 1950s Nuclear weapons (and the means to deliver them) were being stockpiled by potential adversaries on both sides of the iron curtain at an alarming rate. Additionally tensions were on the increase as the Soviet Union increasingly attempted to gain power in areas the West (and particularly the United States) considered to be in its sphere of influence. The Canadian government’s response came in Parliament in 1958 when an extensive array of Civil Defence oriented measures were announced including what was to become the Continuity of Government (CoG) Program.

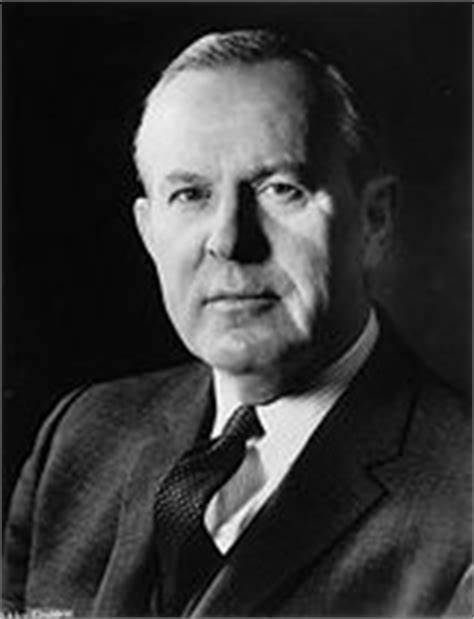

The CoG was intended to provide a thin thread of continuity of legitimate government in the event of a massive nuclear attack. The idea was to ensure sufficient shelter and telecommunications capacity to enable small numbers of federal, provincial and municipal elected officials (along with some supporting public servant advisors) to carry out absolutely essential functions of government in such horrendous circumstances. Between 1959 and 1968 the federal government constructed the Central Emergency Government Headquarters at Carp, Ontario (commonly known as the Diefenbunker) and six other Regional (provincial) “bunkers”. These latter regional bunkers were constructed on military bases across the country. They were specifically responsible for coordinating National Survival operations which involved providing the populace with warning of an imminent attack, distributing pre and post attack evacuation instructions and reentering bombed out areas to rescue as many survivors as possible. While the overall responsibility was in the provincial jurisdiction, the Army was charged with providing the command and control, physical resources and soldiers to support their rescue efforts.

The CoG Program was the basis for the construction of the complete multi-level system of ‘bunker across the nation including of course the Diefenbunker. The CoG was a critical component of Canada’s overall civil and military defence plans during the Cold War.

The Changing Status of Continuity of Government (CoG) and Civil Defence (CD) Preparations – late 1950s into the 1960s.

The extensive preparations authorized and set in motion by the Diefenbaker Government in1958-59 were put on indefinite hold by the 1968 Trudeau Government cabinet decision to stop or delay all civil defence spending.

This ‘freeze’ basically officially continued for the next two decades of the Cold War (with the occasional minor deviation in some of the sub programs to respond to particular international crises). The construction of ‘bunker’ facilities was never resumed.

The result was that all facilities, equipment, procedures and other arrangements completed and in place at that time (1968) were to be retained and maintained but no further expenditures were to be committed to their completion or upgrading.

Continuity of Government versus Continuity of Constitutional Government (and the Central Emergency Government Headquarters – the ‘Diefenbunker’)

The Continuity of Government (CoG) Program was originally presented to Parliament by Prime Minister John D. Diefenbaker in 1958 and, as the excerpts from the August 21, 1958 Parliamentary record Hansard show, his statement was unreservedly supported by the then leader of the opposition, Lester B. Pierson. That in itself demonstrates the importance that out parliamentary leaders at the time attached to this matter. Other NATO nations made similar preparations. The primary purpose of the CoG program from its inception was to protect and support the essentials of ‘executive’ federal government in order to preserve a ‘thin thread’ of legitimate government through the chaos of a nuclear attack on North America. All that was required to pass whatever ’emergency regulations’ would have been required to deal with the situation was the assent of four federal cabinet ministers and the signature of the Governor General.

A primary responsibility of Emergency Preparedness Canada (the agency charged with actualizing the CoG) was to support the implementation and readiness of the program as it was set out originally by Parliament and elaborated upon in PCO’s Emergency Planning Orders.

Then in 1988 the new Emergencies Act came into being (to replace the somewhat heavyhanded – and infamous -War Measures Act) and, more pertinent to our CoG readiness activities, the Emergency Preparedness Act was passed. The latter had a very significant impact (one that probably had not been fully anticipated by the authors of the new legislation) on the Emergency Government Facilities aspects of the CoG. As a result of the fact that the ‘new’ act called for Continuity of Constitutional Government, we had to rethink the numbers aspects of our Central Emergency Government Headquarters protective accommodation arrangements. We consulted a government lawyer who was expert in constitutional law to try to determine what was the minimum we had to do to meet the requirements of the new legislation. The word ‘Constitutional’ meant that government by executive decree was out and that representatives from the legislative and judicial branches of government had to be included in our protected locations.

After much analysis it was concluded that we had to provide for a quorum of each of the House of Commons, the Senate, the Federal Court and the Supreme Court. A quorum of the House of Commons is 20 (including the Speaker), of the Senate is 15, of the Supreme and Federal Courts five each plus various minimum support staffs gave us a ‘doable’ number. As I recall it the total number of ‘new’ occupants that needed to be provided for was only about 55 or 60. We checked out the environmental systems in the bunker and found we were OK for the increased numbers of bodies involved. The main problem was sleeping even with “hot bedding” the norm (and to a lesser extent, suitable ‘office/working’) spaces. In room 457A (across from the EPC HF Emergency Radios Room) we experimented with converting the double bunks to triple bunks. We calculated that there were sufficient civilian double bunked rooms that if modified to triple bunks could accomidate the extra people involved. (Locker space would have been tight). We never got around to sorting out where the quorums of Parliament/Judicial bodies would have met (presumable they could have made use of the War Cabinet room and the 400 level conference room. Nor did the potentially thorny question of whether or not, or to what extent members of the opposition parties would have had to have been included.

The end of the Cold War and the shutting down of the then “new” Continuity of Constitutional Government Program in the early 90s followed eventually by the closing of the Emergency Government Facilities by 1994 put an end to this planning process. In my humble view as a senior emergency planning official we ‘threw the baby out with the bathwater’ when we closed and disposed of the EGFs and stopped related planning. In 2001 it became clear (to me anyway) that that doing so was a mistake. Who knows what current arrangements exist to serve the same purposes as did the CoG program (if any) and how effective they would be in a nuclear-type crisis compared to the extensive and expensive original EGFs and their associated activation plans. We can only hope!

The following article by Dr. Sean M. Maloney is an interesting summary and generally an informative read

“Dr. Strangelove Visits Canada”- Projects RUSTIC, E.A.S.E, and Bridge 1958 to 1963 by Sean Maloney (RMC Professor of History) Published Spring 1997 (click the following link)…

https://davescoldwarcanada.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Dr.-Strangelove-Visits-Canada.pdf

Excerpt from the Introduction: “During the Cold War, many NATO governments developed highly secret contingency plans to maintain the continuity of government (COG) during and after nuclear attack. Canada was no exception. COG planning generally consisted of several elements including legal mechanisms and constitutional matters; document duplication and storage; skeleton bureaucracies; dispersion; transportation; and shelter. All were necessary to keep Canada functioning as a nation in the face of an attack by Soviet atomic and hydrogen bombs. The most misunderstood element of COG planning has been the shelter component. Critics of civil defence programmes argued that protecting government leaders in shelters and not providing similar facilities to the population as a whole was “undemocratic,” designed to maintain the “power elite.”1 The reality of Canada’s COG programme was quite different from this propaganda line and its ability to protect the country’s leaders in underground facilities was much more limited than alleged. This study will concentrate on the strategic context, physical arrangements and concepts of operation developed to maintain the continuity of Canadian government in the era of the greatest danger during the Cold War, 1958 to 1963.”

Some recent treatments of the Continuity of (Constitutional) Government in Canada may be of interest and are referenced below:

The Continuation of Constitutional Government in Canada. This was a 1990 Study Prepared for Emergency Preparedness Canada attempting to define the requirements of the then recently passed Emergency Preparedness Act 1989 so that they could be compared with the then existing physical arrangements (bunkers, etc). From this document senior EPC officials concluded that the highest number of extra people we could add in the CEGHQ (the “Diefenbunker”) would be 100 (preferably 80). We would have to triple bunk the two bunk bedrooms. It would not have been comfortable!

“THE NEED FOR A CANADIAN CONTINUITY OF GOVERNMENT POLICY:

BEING THERE WHEN CANADIANS NEED IT MOST” By LCol J.W. Cunningham

This paper was written (in 2012-13 by a student attending the Canadian Forces College (JCSP 39) in fulfillment of onedocument of the requirements of the Course of Studies for Master of Defence Studies

Canada’s Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness has a legislated

mandate to ensure the necessary arrangements for establishing continuity of

constitutional government (CCG) are in place in the event of an emergency. This

mandate is unsupported by any federal policy document that defines specific

expectations. Whereas continuity of government (COG) is a generally accepted concept,

it is not well understood from theoretical perspective. Academic treatments of the subject

are either highly specific, detailing its application to a particular government, or else

incidental to studies in civil defence or emergency government. By proposing definitions”

to several key terms, and by reviewing case studies of several nations’ experience with

COG (including the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, Switzerland,

Australia and New Zealand), an initial theoretical model for an effective CCG program is

offered. It establishes five essential elements; namely prevention, protection, succession,

relocation, and reconstitution. It further proposes six characteristics of a good CCG

program; namely robustness, simplicity, clarity, immediacy, constitutionality, and

reversibility. Finally, a case is made for the Canadian government to establish and

operationalize its own comprehensive CCG program, built upon the existing, but

disjointed and under-resourced, plans.”

“This research note examines the undefined meaning of the government’s obligations to ensure “continuity of constitutional government” (CCG) as provided for in section(4), para(1), sub-para(l) of the Emergency Management Act, S.C. 2007, c. 15 (Canada, 2007). Specifically, that section gives the minister of public safety and emergency preparedness the responsibility for “establishing the necessary arrangements for the continuity of constitutional government in the event of an emergency,” but the term is itself undefined. The article will canvass the origin of the term and its relationship to other so-called continuity of government (COG) concepts, along with some legal written opinion on what the term might in practice mean, should the minister ever be charged with discharging this responsibility…”