Note: Apologies to David McConnel and academics everywhere but in order to conserve space on this site I have had to (hopefully temporarily) remove the ENDNOTES at the end of each chapter. The fully annotated document is available in electronic and printed form in the Archives of the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum, Carp, Ontario.

Plan for tomorrow …TODAY!

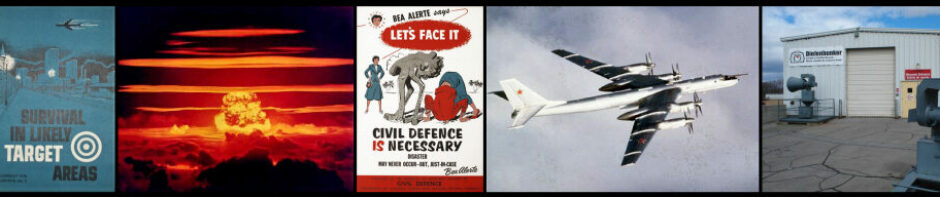

The Story of Emergency Preparedness Canada 1948-1998

by David McConnell Heritage Research Associates Inc. 1998

PREFACE

In 1998, Emergency Preparedness Canada celebrates its 50th anniversary. It was founded in 1948 as a civil defence organization in the Department of National Defence in response to the beginning of the Cold War. Over the next 50 years, it was transferred from department to department, until once again it has returned to National Defence. This study traces the development of the organization against the rise and fall of international tensions. It relates its history to the shifting priorities of domestic politics and to the continuing tensions of federal-provincial relations. It chronicles the slow change from strict civil defence, or wartime emergency planning, to the all-hazards approach of emergency preparedness in the 1990s. This is a record of dedicated public servants who continued on in the face of an indifferent public and hostile politicians. This is a story of fluctuating budgets and staff, of a program that stayed the course as public opinion and government policy determined its course and acknowledged its value. It is the history of a national institution

The following account is the product of early research on the predecessors of EPC and of new research on the organization’s history since 1974. The files of EPC contained a draft history of emergency measures from Air Raid Precautions in the Second World War to 1974. Its origins are unclear. One section dealing with the Second World War was written during July and August 1949 by R. J. Rennie, a wartime major in the artillery, who had an MA in history.i It has been suggested that the section from 1948 to 1951 was written by J. F. Wallace, a long time employee of the organization.ii The rest of the draft history may be the work of summer students hired to record ongoing events. The account of the period from 1951 to 1959, for example is attributed to a Susan McCoy.iii The authorship of the remainder is unknown.

Rather than entirely redo this early history, the present author agreed to use the draft history as the basis for the history up to 1974. Its references and account were verified and then the author revised, reorganized, and elaborated the information it contained as he saw fit. Nevertheless, the contributions of Major Rennie, J. F. Wallace, Susan McCoy, and the other anonymous writers are substantial, particularly with regard to content, and are acknowledged. S. N. White, retired Director General Plans, was asked by EPC to comment on the early draft history and his comments are gratefully received. That portion of the history from 1968 to the present is almost entirely the work of the present author.

Finally, I would like to thank Margaret Carter, Heritage Research Associates Inc., for her editorial assistance and Mike Braham, Director, Emergency Programs and Exercises, for his supervision of the project and his patience in seeing it through to completion.

iRG 29, Records of the Department of National Health and Welfare, Vol. 639, File 100-1-10.

iiPersonal Correspondence, S. N. White to Dave Peters, EPC, 12 June 1997.

iiiLawrence S. Hagen, Civil Defence: The Case for Reconsideration, National Security Series No. 7 (Kingston, Ont.: Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University, 1977), p. 82, fn. 58.

Prologue

Civil Defence in the Second World War: The Air Raid Precautions Organization (ARP)

I Introduction

Civil defence, or passive defence as it was called before the Second World War, “…may be defined as comprising those measures of protection which can be taken on the ground to minimize the effect of attacks from the air, both of personnel and material.” Some of the measures, such as setting up warning systems, can be prepared in advance. Others, such as population evacuation, can be instituted only upon warning or expectation of attack. In all cases, the extent of planning, training, and implementation which occurs prior to the attack increases the effectiveness of the measures.

The origins of civil defence in Canada can be traced back to the creation of the Air Raid Precautions organization (ARP) by the federal government in the Department of Pensions and National Health before the Second World War. Since passive defence was an aspect of national defence, it was regarded as a federal responsibility. The protective measures required to implement it, however, were local by their very nature. While this dichotomy was recognized in theory, until the jurisdictional, financial, and practical responsibilities were precisely defined, there was constant federal-provincial tension. Political fears of national disunity associated with questions of war shrouded pre-war planning in secrecy and prevented consultation with the provincial governments. Consequently, the first two years of the war were marked by frantic activity at the local and provincial levels and ad hoc solutions to problems at the federal level. Not until after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor did the three levels of governments work out acceptable policies to establish an efficient civil defence organization in Canada.

II Pre-War Preparations

As the international situation in the Far East and in Europe worsened in the mid-1930s, the newly elected Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King began slowly and deliberately to prepare for a possible war. In August 1936, the government established the Canadian Defence Committee as a committee of cabinet: its mission was to plan for the defence of Canada. At its first meeting the committee discussed the danger of air attack and the provision of adequate protection for the civilian population. On the recommendation of the Department of National Defence, the Prime Minister approved the creation of six interdepartmental committees in April 1937. One of them was the Interdepartmental Air Raid Precautions (ARP) Committee whose purpose was to examine the problem of air raid precautions (hence its name) and to recommend actions to be taken by federal authorities to protect the civilian population. Almost a year later, in March 1938, an order-in-council formally established these committees, stipulating that they were to report to the Minister of National Defence rather than to the Defence Committee.

Because measures to protect the public from the effects of air raids (especially gas attacks) were likely to be medical or health related, the Interdepartmental ARP Committee was placed under the authority of the Department of Pensions and National Health with the Deputy-Minister of that department, Dr. R. E. L. Wodehouse, as chairperson. This committee, which represented eight federal departments, began its deliberations on 29 March 1938. It was instructed “To enquire into and report upon non-military measures which should be adopted against the possibility of air attacks, including gas attacks, and the co-ordination of the action of the various authorities concerned, both public and private.” It studied British precedents, including the 1934 Handbook of Passive Air Defence. The Department of National Defence provided estimates of the forms and scale of air attack on east and west coast cities in the event of an European or Asian war as a basis for planning. Any consultation with provincial or municipal authorities was precluded, however, by the government’s insistence on secrecy lest it be thought that Canada was preparing for war.

The first (and last) report of the Interdepartmental ARP Committee was submitted on 30 June and approved by Cabinet in late July 1938. In this report, the committee raised jurisdictional and financial questions which would continue to bedevil the ARP organization throughout the Second World War. As an aspect of national defence, the committee argued, passive defence was the primary responsibility of the federal government which should prepare a handbook outlining the shape of the organization to be created and the nature of the passive defence measures required. Of necessity, implementation of these detailed schemes would devolve upon the municipalities. At this local level, the necessary administrative machinery already existed and could be augmented by volunteer workers. The federal government would bear the cost of services beyond those which a municipality had in place, such as producing the handbook, of procuring gas masks for the civilian population, of buying decontamination materials, and of training instructors. The link between the federal and municipal governments would, it was hoped, be provided by the provincial government, an arrangement which confirmed the existing political situation. The Interdepartmental ARP Committee also recommended that the Department of Pensions and National Health, which already dealt with several provinces and through them the municipal bodies on matters pertaining to the physical well-being of the population, assume responsibility for ARP. After Cabinet approval of this report, the committee effectively ceased to function.

As a follow-up, Wodehouse set up a committee of six officials from the Department of Pensions and National Health to continue to develop federal aspects of the program. He enlarged this group of officials by adding two representatives from the Department of National Defence, the Director of the St. John Ambulance Association, and the Dominion Fire Commissioner. Wodehouse also provided the committee with ambitious terms of reference, too ambitious as it turned out for the government. Its mission was to consider

all points arising in connection with air raid precautions schemes, to act, when necessary, as the medium of consultation with outside authorities and also to provide generally for co-ordination, not only between government departments but with such other authorities as may be concerned. It is responsible for submitting to the interdepartmental committee matters on policy on which decisions are required, together with recommendations as to the course of action suggested.

The major accomplishment of the Departmental ARP Committee was to produce Air Raid Precautions, General Information for the Civil Authorities, a Canadian version of the British Handbook of Passive Air Defence issued in 1934. Amended and adapted to the Canadian situation, this handbook was intended to provide instructions to Canadian provincial and municipal authorities when the time came to set up local ARP organizations. Although 500 copies were printed in October 1938, they were not issued until August 1939. (In addition, 700 sets of handbooks and memoranda about particular aspects of ARP were purchased from the British government.) As well, the committee prepared requisition and other forms and instructional material for local use. It also collected data on the population and resources of vulnerable areas, on the availability of fire fighting equipment in them, on the dangers of infection of crops and farm animals, and on other matters it considered relevant. It suggested an alternative plan of action if the provincial governments refused to assume their designated roles and recommended the creation and organization of an ARP headquarters in Ottawa.

Having compiled the handbook and collected a great deal of information, the Departmental ARP Committee submitted a report to the Minister of Pensions and National Health on 5 December 1938. The committee now wanted to move ahead with more concrete proposals and to involve the provincial authorities. It recommended that plans should be made for the evacuation of non-essential civilians from areas that were either under attack or likely to be attacked. It saw the need to set up first-aid stations, build up Canadian stocks of narcotics, and provide additional hospital accommodation and equipment in vulnerable areas and receiving areas. It suggested that warning systems be installed in vulnerable areas and that air raid shelters be built. To deal with the destruction of an aerial attack, it recommended the provision of additional fire-fighting equipment, the training of auxiliary firemen, and the procuring of wrecking equipment in vulnerable centres. Wodehouse recommend to his minister that a budget be prepared for cabinet approval to carry out the committee’s plans. The necessity to defend spending such large sums on ARP in the House of Commons created a difficulty. This, together with the publicity that would undoubtedly accompany a suggestion that the provincial authorities be consulted undoubtedly convinced the government to halt all progress in ARP measures. The Department of Pensions and National Health was forced to mark time until the Polish crisis in August 1939.

While the federal government had clearly recognized the need for passive defence planning in the pre-war period, it was only prepared to act within a restricted sphere. Financial restraint and the danger of national disunity limited activity to the provision of a secret rudimentary plan of action and a skeleton federal organization. Because the government insisted on secrecy in preparing the ARP scheme, there was no chance to consult with provincial and municipal authorities, especially on the sharing of responsibilities and financing. Such consultation could have obviated the subsequent wrangling over finances early in the war. As well, a clear-cut announcement of government policy on ARP measures might have restrained the hysteria following the fall of France in 1940 as local authorities and agencies scrambled to put passive defence measures in place. Ultimately, the officials of the Department of Pensions and National Health could do little more than copy British measures. Secrecy prevented these schemes from being tested against Canadian conditions.

III The Development of ARP, August 1939 – December 1941

As Hitler prepared to invade Poland in August 1939 and pushed Europe to the brink of war, the federal government acted swiftly to set up a civil defence system before war was declared. In accordance with a pre-arranged plan, members of the Departmental Committee in the Department of Pensions and National Health were sent to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and British Columbia on 25 August and to Quebec a week later. The Government of Ontario, however, refused to participate. As federal officials met with representatives of the provincial governments and explained the principles of passive defence, they suggested that steps be taken to meet emergencies and offered federal co-operation. The legal basis for implementing ARP measures was established by Sections 32-36 inclusive of the Defence of Canada Regulations (DCR) promulgated on 3 September 1939. Under these regulations, the Minister of National Defence or the Minister of Pensions and National Health, or his delegate (usually the provincial premier), had sweeping powers to order evacuations, to put precautionary measures in place against attack, to close or destroy damaged or contaminated buildings, to limit lights and sounds, and to institute curfews.

To carry out federal ARP responsibilities, an officer of the Department of Pensions and National Health was appointed to assume control as Executive of Air Raid Precautions for Canada on 1 September. The Departmental Committee would advise him on policy matters. His duties were never specifically defined, but many evolved over the next two years. He advised provincial and municipal ARP committees, made provincial tours of inspection, maintained liaison with the Home Office in the United Kingdom and later with the Office of Civil Defence in the United States, and supervised the manufacture and distribution of ARP equipment. He also prepared and distributed ARP publications, made public addresses, and advised the Minister and Deputy Minister on policy questions.

Federal civil defence intentions were outlined in the handbook, Air Raid Precautions, General Information for the Civil Authorities, which the Departmental Committee had prepared in 1938. This document provided the basis for provincial and local organization and described ARP services. Usually, an ARP Committee of the provincial government was set up to deal with general policy and to advise those municipalities declared by the Department of National Defence to be vulnerable to attack. Municipal or local committees, made up of volunteers, were established to be responsible for the detailed organization of ARP measures. Auxiliary firemen and auxiliary public utility workers were designated to maintain vital services during an emergency. First-aid workers’ duties included staffing first-aid posts, acting as stretcher bearers, driving ambulances, and generally taking care of casualties after an attack. Air raid wardens were to act as auxiliary police, with authority for maintaining order during a blackout practice or an actual air raid and responsibility for transmitting necessary information to the public. Except for Ontario, the designated provincial governments responded quickly and enthusiastically to these federal overtures. Each put its own individual stamp on provincial ARP organization.

Nova Scotia established an ARP committee on 29 August 1939, and local units were set up in Halifax and Sydney shortly thereafter. For all intents and purposes the provincial and Halifax committees operated as one, concerning themselves solely with Halifax. Cape Breton acted on its own and the ARP organization in Sydney extended to embrace local committees throughout the island. In Halifax, the main concerns were practicing blackouts and setting up first-aid posts. While the federal government undertook to provide first-aid, anti-gas, and decontamination equipment, it arrived very slowly. Halifax provided its own electronically operated air raid warning sirens.

Since Saint John was the only vulnerable area in New Brunswick, federal and provincial authorities agreed that the local ARP committee would also be the provincial committee. It began by establishing first-aid posts and holding blackout practices, although it also prepared an elaborate evacuation scheme to remove non-essential people to the interior of the province. While Moncton had not been declared a vulnerable area, it lobbied to have an ARP organization. When the Department of National Defence declared that there was danger of sabotage, that city too received some federal funding. By July 1940, excitement was so high that the provincial government decided to set up a province-wide skeleton ARP organization without federal aid. By this time, ARP organizations in Saint John and Moncton were well underway. Both established complete warden and first-aid organizations. Both had air raid warning systems: Saint John provided its own, while Moncton secured federal aid to install its system.

In late August 1939, British Columbia established a provincial ARP committee and by 7 September, local committees for the Victoria and Vancouver areas were set up. In each case, sub-committees were appointed to handle specific responsibilities. Initially, British Columbia’s ARP organization was most concerned to detect and deal with damage resulting from sabotage. No air raid warning systems were installed or blackout exercises held until 1941. ARP measures were, however, put in place in Prince Rupert at the end of 1939. On its own initiative, the province also organized Nanaimo. Bickering among the participating municipalities resulted in the disbanding of the Vancouver area committee in May 1941 and of the Victoria area committee at the end of the year. They were replaced by separate committees in each of the area municipalities.

In Quebec, the organization of ARP committees was delayed during a provincial election campaign resulting in the defeat of the Duplessis government. By December 1939, a provincial committee was established along with local units in Montréal and Québec City. The southern and eastern parts of the province were organized without federal funding. By December 1940, the whole of the St. Lawrence Valley from Gaspé to the Eastern Townships was covered by a net of organizations that included an air raid warden service, an auxiliary fire service, first-aid posts with first-aid workers, and auxiliary municipal workers. There was also an armed Mobile Force organized to combat subversive activities. Despite all this activity, neither Montréal nor Québec City had held blackout exercises.

By August 1940, public opinion forced the Ontario government to reconsider its original refusal to participate in the ARP program. On 12 September, a provincial ARP committee was established by order-in-council. By March 1941, it had organized 43 ARP units in the 14 vulnerable areas. In May, the first blackout exercise was held in Toronto. A Volunteer Corps previously organized to guard certain installations against sabotage was drawn into the organization to perform warden duties and other services. The Committee also prepared manuals on the warden service, engineering services, and fire service, the last of which was adopted by federal authorities for use throughout Canada.

Because of the large number of government agencies and employees in Ottawa and Hull, the federal ARP office decided to organize a separate committee for the Federal District. Established in October 1940, it reported directly to the Minister of Pensions and National Health. By April 1941, it had set up some 30 first-aid posts and enrolled about 2,000 wardens. The Federal District organization held its first complete blackout on 26 October 1941.

As the war continued, initial provincial enthusiasm for ARP proposals was inevitably replaced by questions of federal-provincial jurisdiction. Although federal authorities claimed they had primary responsibility for ARP as an aspect of national defence, they envisioned its implementation at the local level by volunteers using existing organizations and services. Unfortunately there was no clear-cut definition of federal financial responsibility or of the amount of equipment that was needed. Ad hoc federal reactions to provincial requests increased both confusion and frustration. With no clear definition of financial authority, no precedents or firm figures for planning, relationships soon deteriorated.

As the provinces became increasingly involved in civil defence activities, it was soon evident they took a wider view of federal responsibilities. Before long they began making demands for money to pay the salaries of provincial officials, for office space, and administrative costs. These demands were met by a grant of $5,000 for each of the four provinces in January 1940 accompanied by a warning to expect no more. Nova Scotia and British Columbia managed within the limit of these funds, but New Brunswick soon spent her grant and returned for more. Quebec submitted accounts for costs of non-designated items, which the federal government initially rejected but later settled in favour of Quebec after a second grant was made to the province.

Immersed in financial wrangling, the federal government inconsistently stated that provision and maintenance of ARP warning systems and fire fighting equipment were local responsibilities. Both Moncton and Saint John worked out compromises for sharing the cost of their warning systems, and by the end of 1941, the federal government had funded the installation of sirens in Victoria, Vancouver, Prince Rupert, Toronto, Ottawa, Hull, Montréal, and Québec City. Also, in July 1941, the federal program ordered 200 portable pumps and over a million feet of fire hose, which were placed at the disposal of the provincial ARP committees.

Given the preliminary state of pre-war planning, unanticipated responsibilities were bound to arise. One was provision of compensation for ARP volunteers injured or killed on duty. The provincial governments flatly refused to accept it. After initially evading the issue, the federal government agreed in September 1941 to provide pensions for ARP workers injured during training or by enemy action and for dependents if the workers were killed.

In addition, there was a legal question of whether the Minister of National Defence or the Minister of Pensions and National Health had sufficient discretionary power to enforce compliance with ARP orders issued under the Defence of Canada Regulations. Federal officials initially preferred to secure co-operation by persuasion and good will. When, in May 1941, a Superior Court judge in Quebec dismissed a charge of failing to comply with blackout regulations on the grounds that the federal power had not been properly delegated to provincial officials, the federal government took action to clarify its position. The Regulations were amended, transferring authority solely to the Minister of Pensions and National Health and simplifying the issuing of orders and regulations, including the power of delegation. Further amendments gave the Minister sweeping discretionary powers to restrict public assemblies and outdoor lighting in areas considered vulnerable to hostile attack. The federal and provincial authorities now had strong legal authority for any ARP measures that might be considered necessary.

At the end of 1941, provision for Canada’s civil defence was well underway. ARP groups existed in about 150 communities and almost 95,000 volunteers were registered as ARP workers. First-aid training was well advanced, special courses had begun for auxiliary firemen, and, with the limited equipment available, some anti-gas training was occurring. The federal government had spent $350,000 on equipment (most of it for first-aid), $40,000 on incidental expenses for the provinces, and $10,000 on training through the St. John Ambulance Association. Orders had been placed for fire equipment and sirens, and a nation-wide issue of gas masks was under consideration. Although local ARP organizations varied greatly in character and achievement, each one addressed needs it considered important in its area. The St. John Ambulance Association was noteworthy for the thorough instruction of first-aid workers provided by its volunteers. In truth, most other volunteers probably did not thoroughly understand their jobs. They suffered from a lack of proper equipment, inability to train under realistic conditions, and a dearth of properly qualified and experienced instructors. It is fortunate that Canada did not receive even a small-scale air attack between 1939 and 1941 when ARP was insufficiently organized and equipped. Even after 1941, there still remained conflicts between the federal and provincial governments over financing. Training, while going on, was largely incomplete. Supplies of equipment were inadequate. Although a beginning had been made during this early period, much remained to be done.

IV The Maturing of ARP, 1942 – 1946

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 gave new emphasis to the importance of ARP, especially in British Columbia. Even before that disaster, the Chiefs of Staff had extended their definition of the area exposed to definite risk of air attack to include all of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, all the lower St. Lawrence Valley, the coastline of British Columbia, and Vancouver Island. Western Quebec north to James Bay, much of north-eastern Ontario, southern Ontario, and British Columbia west of the Cascade Mountains were deemed areas of slight risk. In December 1941, all of these areas were included in the compensation order covering the injury or death of volunteers. In addition, the responsibilities of both federal and provincial ARP agencies were increased to emphasize the growing importance of passive defence. Effective 1 January 1942, R. J. Manion (the former leader of the federal Conservative Party) was appointed Director of Civil Air Raid Precautions with deputy minister status, responsible only to the Minister of Pensions and National Health. Until his death in July 1943, Manion approached his duties with enthusiasm and energy. According to his successor, Brigadier General Alexander Ross, much of the success of the ARP organization until the end of the war, especially in the securing of adequate supplies of equipment, was due to his efforts.

Manion moved to eradicate the serious flaws in ARP organization which the first two years of the war had revealed. In particular, the federal-provincial financial policy was inconsistent. After a false start in February 1942, the ARP office developed a satisfactory system of assessing provincial claims to federal grants in June 1942. It was based on the degree of risk each province faced, the areas involved, and the density of population. The provinces shared the grants with the municipalities (a 40/60 split was suggested) and the municipalities were expected to match the federal grant, although few did. Usually the amount available was greater than the claims submitted. This arrangement worked so well that it was continued until the end of the fiscal year 1944-5 when most ARP organizations were disbanded.

Another problem clarified under Manion’s direction was the nature and extent of equipment the federal government was to provide to ARP units. A complex policy for issuing equipment was worked out early in 1942. This established a basis for assessing requirements using the number of ARP workers in each area and degree of defence risk associated with local activity. A list of equipment was established for particular types of jobs and activities (such as fire-fighting and first aid), then equipment was distributed according to a priority system of designated risk. In 1942-3, additional orders were placed for sirens, first-aid, anti-gas, and fire fighting equipment and by the end of that fiscal year, $5 million worth of equipment had been provided to the six organized provinces and large quantities had been stockpiled.

Although gas was never actually used as a weapon in the Second World War, the possibility of gas attacks was taken very seriously. In April 1942, it was decided to equip all ARP workers with special respirators and to distribute gas masks to the whole civilian population in areas of definite risk. An order for two million civilian respirators, which included special types for children, babies, and helpless hospital patients, was placed with the Dominion Rubber Company. By December 1942, these masks were in the hands of the provinces but, despite some limited attempts to distribute them, most remained in storage unassembled. At the end of the war they were turned over to the War Assets Corporation.

Throughout 1942, gas advisers or officers were appointed to plan the ARP defence program for federal and provincial organizations and committees in larger centres. Gas instructors were trained at McGill University, and in February 1943, gas training began in many centres across Canada. Local decontamination squads were instructed, and gas cleansing centres were set up. When the possibility of enemy gas attacks became remote at the end of 1943, Brigadier General Alexander Ross cancelled further orders for anti-gas equipment and clothing. Ross had become Director of ARP after Manion’s death on 2 July of that year.

The war with Japan revived the possibility that it would be necessary to evacuate the civilian population from vulnerable areas. The Departmental Committee had considered this eventuality before the war, but only New Brunswick had prepared an evacuation plan to transport the non-essential population of Saint John to the interior of the province. In 1942, the federal government realized that areas on both the east and west coasts might have to be evacuated and an evacuation officer for each coast was appointed to the staff of the Director of ARP. Danger to Vancouver Island if the Japanese dropped incendiaries in its forests was the primary concern. British Columbia began developing evacuation plans for the island, but before reception arrangements on the mainland were complete the possibility of attack had become remote. In 1943, the federal evacuation officers were transferred to other duties.

During his time as Director of Civil Air Raid Precautions, Manion had continually asserted the importance of ARP as an aspect of national defence in his dealings with the Department of National Defence. Although ARP officials reported good co-operation with the military establishment in such local matters as developing an efficient air raid warning communications system, Manion felt that liaison between his office and National Defence officials in Ottawa was inadequate. He insisted that one officer from each service attend his staff conferences despite the reluctance of the Chiefs of Staff. After Manion’s death, however, Brigadier General Ross cancelled the new appointment of a full-time staff officer to the ARP staff. Ross had no compunction about approaching the Chiefs of Staff directly. Just after his appointment, a second area of tension between ARP and the military flared. This was the continuing loss of key ARP personnel to the armed forces, especially to the Reserve Army in British Columbia. In 1943 the Minister of National Defence issued instructions not to recruit key ARP members without the permission of the provincial committee.

Brigadier General Ross was just as aggressive as his predecessor in asserting ARP’s importance. In 1943, he recommended to the federal government that the name of his office be changed to Director of Civil Defence and that the ARP organization be known as Civil Defence. Such a change was in line with the nomenclature in the United States and Great Britain and, with provincial agreement, made for uniformity of name throughout the country. This change also suggests that, in the minds of some officials at least, Civil Defence had become an integral part of National Defence strategy. ARP had progressed from performing a peripheral role in air raid protection to claiming an important function in the defence of Canada.

While Manion and Ross were overhauling the central organization, the tempo of activity in the provinces was picking up. Local ARP organizations in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick began very actively training and recruiting in 1942 and 1943. In November 1941, Prince Edward Island was declared a vulnerable area and organized shortly thereafter, but Islanders never took ARP very seriously. Lighting restrictions were imposed in all three provinces in January 1942, although they were progressively relaxed until they were removed in 1944. Even though they were never called on to respond to an air raid, the ARP organizations demonstrated their usefulness in dealing with civil emergencies. In New Brunswick, workers contained several forest fires. In Nova Scotia (where the provincial organization was deliberately renamed the Provincial Civilian Emergency Committee), it responded to explosions at the Naval Arsenal in Dartmouth in 1944 and again in 1945. Once it became clear that the war was coming to an end, these organizations were disbanded. Removal of the siren system from Halifax in October 1945 marked the end of wartime Civil Defence in the Maritimes.

Civil defence in Quebec followed a variation on the same pattern. Much of the province had been organized before parts of it were declared to be vulnerable areas. By March 1943, Quebec’s organization had reached its peak with 145 ARP units staffed by 37,600 registered workers. While the number of units had decreased to 139 by March 1944, the number of workers had increased to 53,860. It is difficult to estimate the efficiency of the organization in Quebec, but the province was ready for a complete blackout by February 1942. A dimout was ordered until the end of navigation from Rivière du Loup to Gaspé because of submarine activity in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in September 1942. This was reimposed the following spring and extended to cover a greater area along the north shore from the Saguenay River to the Labrador border. The dimout was enforced through the co-operation of ARP units, the Aircraft Detection Corps, the Reserve Army, and the RCMP. It represents Quebec’s major ARP accomplishment.

The Ontario Civilian Defence Committee developed the most elaborate organization in Canada by March 1943 with 71,587 registered workers in 123 ARP units in 15 areas. The chairman and vice-chairman both applied themselves with great energy to their tasks and forced the federal government to clarify the legal and financial arrangements of ARP. The Fire Marshall of Ontario was also Manion’s advisor on fire-fighting equipment and methods, and his Fire Services Manual was adopted Canada-wide. The Chiefs of Staff excluded Ontario from the risk of attack in November 1943, however, and most of the Ontario ARP organization was subsequently disbanded. Committees in the border communities of Sault St. Marie, Sarnia, Windsor, and Niagara Falls continued to function because their warning facilities were combined with those of the neighbouring American cities. Thus, 22 ARP units (14,180 registered workers) maintained their organization until the end of 1944, reporting directly to the federal office.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, ARP preparations intensified in British Columbia. The Premier of British Columbia reorganized the provincial ARP committee to deal with the increased demands and to control the politic-ridden ARP organizations in Vancouver and Victoria. He created a Civilian Protection Committee of four officials along with an Advisory Council whose main purpose was to eliminate the bickering between the different associations and groups involved in ARP. By March 1943, 139 units had been formed with 62,845 registered workers. A warning system of sirens was installed at the end of 1942 and the province held wide-spread blackout exercises. An evacuation scheme was also developed before federal evacuation officers were removed in October 1943. With the disbanding of ARP units in Ontario at the end of 1943, more fire fighting and anti-gas equipment was sent to the west coast. Japanese balloon bombs were dropped on B.C. in February 1945, prolonging the life of the Civilian Protection Committee in British Columbia until August.

The federal government began to wind down the Civil Defence organization once the risk of air raids diminished. As the Allies began to win the war, Ontario’s ARP organization was the first to be disbanded in November 1943. The central ARP office was the next to be weakened when the federal government decided that a full time Director of Civil Defence was no longer needed in August 1944. Brigadier General Ross, however, agreed to stay on without pay. Temporary success of the German Ardennes offensive in December 1944 delayed further destruction for a time. In 1945, the provinces were advised to disband their organizations whenever they wished, and they were notified that all federal aid would cease with the end of the fiscal year on 31 March 1945. Because of their special circumstances, only the British Columbia and Halifax groups continued to function beyond that date.

Provincial committees were instructed to liquidate their financial obligations, account for all equipment issued to them, and turn it over to the War Assets Corporation. Personal equipment could be retained by workers, all of whom received a certificate signed by the Prime Minister and the Director of Civil Defence acknowledging their service to the country. Finally on 14 September 1945, the relevant Defence of Canada Regulations (except for parts of Regulation 35) were rescinded thus removing most of the restrictive measures for civil defence purposes.

During the war, about 775 communities were organized and received some equipment for ARP purposes. At its peak, about 280,000 workers were enrolled, most of whom were unpaid volunteers. In many smaller communities, the wartime ARP organizations, especially auxiliary fire services, did not disband but served on after the war. The governments of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and British Columbia purchased all fire fighting equipment provided by the federal government with the result that more than 500 small communities, previously without organized fire protection, obtained organized, trained, and equipped fire brigades.

V Conclusion

Conceived by a government plagued by financial problems and the fear of national disunity, ARP could do little other than plan in secrecy before the Second World War. Once war came, the federal organization scrambled to bring vulnerable provinces onside, offering them organizational advice, limited financing, promises of equipment, and some training. It was not until after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that ARP organizations began to coalesce. Under the energetic leadership of R. J. Manion and his successor Brigadier General Alexander Ross, financial problems with the provinces were solved and sufficient supplies and adequate training provided. By late 1943, danger had clearly passed and the ARP organizations were slowly disbanded. Even though ARP was never tested during the Second World War, it cast a long shadow over civil defence organizations in Canada in the Cold War era. The ARP philosophy that civil defence should be a voluntary local responsibility guided and supported by a central organization was to persist for years to come.

Table of Contents

Preface

Prologue – Civil Defence in the Second World War: The Air Raid Precautions Organization

Chapter 1 – Civil Defence in Canada: 1948-1957

Chapter 2 – The Rise and Fall of the Emergency Measures Organization: 1957-1968

Chapter 3 – The Fall and Rise of Civil Emergency Measures: 1968-1981

Chapter 4 – The Reform of Civil Emergency Measures: 1981-1988

Chapter 5 – Toward the Millennium — Emergency Preparedness Planning in the 1990s

Chapter 6 – Summary and Conclusion

Bibliography

List of Appendices (Critical Documents were provided as appendices in separate volume).

Webmaster note: The referenced documents are in the archives of the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War museum in the sole-copy printed version of this document. An electronic version has not yet been produced and thus not included here.

Chapter I- Civil Defence in Canada: 1948-1959

I Introduction

Following the Second World War, the federal government wanted to have done with all things warlike, including civil defence, and get on with building a peaceful country. Its optimistic intent, however, could not be sustained in the hostile post-war international atmosphere created by the Cold War and the destructive potential of the atomic bomb. In 1948, building on the experience of ARP, the federal government decided to re-establish a civil defence organization. Once again federal officials assumed a planning and coordinating role, providing training, research, and limited financing. As before, civil defence services were to be provided through the extension of the functions of existing agencies, public and private, and by the efforts of volunteers. Civil defence was again decentralized, with the federal and provincial governments responsible for planning, training, and coordinating and the local governments responsible for implementing the program. Although civil defence was reborn within the Department of National Defence, it was shortly transferred to the Department of National Health and Welfare because of the nature of the services it would supply to the civil population in the event of war. From 1951 to 1958, the Department of National Health and Welfare coordinated civil defence, until new forces, national and international, forced a re-evaluation.

II Civil Defence in the Department of National Defence 1948-51

Brigadier General Alexander Ross, the Director of Civil Defence at the end of the Second World War, believed that civil defence was an essential element of national defence: consideration of a permanent civil defence organization should be included in any post-war defence planning. Before retiring, Ross submitted a report to the government outlining the nature of such an organization and the problems that would have to be solved in establishing it. In his view, federal and provincial governments should assume responsibility for planning and training, while the municipality served as the operational unit. Ross emphasized that local authorities would be ultimately responsible for civil defence, most of the work volunteer. Although financing the necessary skeleton organizations and the purchase of equipment would have to be met through federal assistance, the federal government should refrain, as far as possible, from exercising any direct control. The federal role would be to advise and coordinate, supplying such assistance as might be required to develop local resources. Ross envisaged the peacetime creation of a skeleton organization in every locality ready to implement an approved civil defence scheme. The extent of local resources should be inventoried and the amount of auxiliary aid needed should be estimated. Key personnel should be appointed to every branch of the organization, then trained to put the scheme into operation on the shortest notice. Such measures would permit rapid and complete mobilization in the event of surprise attack.i

Ross’s report was ignored by a government that was intent on rapid demobilization and on building a peace-time Canada, not preparing for another war. It soon became very clear, however, that the post-war world was still very dangerous. Even before the war was over, the Igor Gouzenko spy case in Ottawa had signalled that the Soviet Union had hostile intent. By 1946, Churchill described an Iron Curtain descending on eastern Europe, and Communist threats were being defeated in Greece and Italy. In February 1948, a communist coup replaced the legitimate government in Czechoslovakia. One month later the Soviets blockaded West Berlin. Although the immediate Soviet threat was in Europe, the United States began to plan for the defence of North America. Despite doubts about the necessity of these defensive measures, the Canadian government felt compelled to reassure the Americans in order to maintain Canadian sovereignty. Canada continued to sit on the Permanent Joint Board of Defence and in February 1947, it signed a bilateral agreement committing Canada to the use of American weapons, equipment, training methods, and communications.ii Although the Soviet Union did not explode an atomic bomb until 1949, her scientists were known to be actively pursuing atomic research. In this darkening world, the question of civil defence was raised once again.

Early in 1948, the Minister of National Defence directed the Chairman of the Defence Research Board, Dr. O. M. Solandt, to prepare an appreciation and to make recommendations concerning civil defence planning and organization. In April of that year, Solandt sent a memorandum to the Defence Committee of Cabinet. The contents were based on the assumption that any future war would likely include an attack on the North American continent, either by air or sabotage. Solandt defined civil defence clearly as an aspect of total war:

all those defensive measures which can be taken on behalf of the civilian population to insure that when such an attack is made the will to resist is maintained, and the economic and social organization of the community will function effectively in support of offensive operations.

He recognized that any plan for civil defence would have to take into account the difficulties arising from climatic and geographic conditions. He also acknowledged the jurisdictional division of responsibility between the federal and provincial governments. Preventive measures, such as early warning, internal security, industrial dispersion, and evacuation, would call for planning and execution on a national and regional level. Even remedial measures would require centralized planning due to the magnitude of the problems associated with an atomic explosion, although the organization and delivery of health and welfare services would still remain a local or municipal responsibility. The local and volunteer nature of civil defence was still clearly recognized.

The report recommended that an agency responsible for planning civil defence should be established within the Department of National Defence because of the need for close integration of civil and military defence plans. A Civil Defence Advisor to the Minister should be appointed to begin planning the creation of this new agency. He should “…be capable of taking full charge of Civil Defence in time of war. He must be experienced in administration and in public relations and have served in one of the Armed Services, preferably the Army.” In his planning he should delegate all possible responsibilities to existing departments of government and other agencies. At the same time, he should retain responsibility for ensuring that federal government policy was clearly formulated and implemented. The Advisor and his staff should also handle major problems which could not be delegated elsewhere, such as those associated with shelter policy, decentralization of industry, timing of implementation, publicity, and decisions concerning the scale of civil defence preparedness relative to other defence needs.iii

Effective 1 October 1948, Major General Frederick Frank Worthington, recently retired from the Army, was appointed as Special Advisor to the Minister of National Defence to act as Civil Defence Co-ordinator.iv His responsibilities were succinctly stated:

The Civil Defence Coordinator will be responsible to keep abreast of the Civil Defence situation and plan the necessary organization with the appropriate agencies of the federal, provincial and municipal governments. At this stage he will act purely in an advisory capacity and will be assisted by a committee representing various government departments concerned. He will keep informed of Civil Defence requirements and developments in other countries and advise on measures that changing circumstances might require in this country.v

His immediate task was to study the requirements of civil defence and to make recommendations to the Minister of National Defence about measures that should be taken to meet a possible emergency. In formulating this plan, he was directed to take into account current thinking on the nature of possible enemy attacks against Canada. At the same time he was not to lose sight of such requirements as dispersal of industry, evacuation of population, provision of deep shelters, and other long term considerations.vi

In November and December, Worthington visited all the provinces to explain to the provincial governments the probable nature of the federal civil defence organization and to ascertain particular problems affecting each province.vii (While he was in Regina, he met with Brigadier General Alexander Ross to benefit from his Second World War experience.viii) In the meetings with provincial officials (usually the premiers), he stressed that the primary object of civil defence was to minimize the effect of disaster on the civil population, on industry, on commerce, and on public utilities in order that normal functions might be resumed with as little delay as possible. He explained that he wished to create an organization which could expand rapidly in time of a national emergency. Since the proposed plan was to work through provincial civil defence organizations, it was hoped that the provincial governments would set these up in the near future. It was suggested that the organization should include the premier of the province as head, with a full-time Director and a small staff capable of rapid expansion. In general, the provincial officials reacted positively to the federal initiative, indicating the need for more civil defence planning both at the federal and provincial levels.ix

In January and February 1949, Worthington visited the United Kingdom and other Western European countries to make a thorough study of their civil defence organizations. He found the trip to be useful, both for isolating problems and for suggesting solutions. For example, very early in his study Worthington became convinced that most civil defence functions could be placed in federal government departments as an extension of their peacetime duties. Under this arrangement the civil defence agency would supply only the necessary co-ordination and direction in emergency planning.x During the trip he also found that civil defence organizations in several countries played an active role in the event of a natural disaster.xi These and other ideas were incorporated into his thinking as he prepared a plan for civil defence in Canada.

On the 17 March 1949, Worthington presented an outline plan for a civil defence organization to the Minister of National Defence.xii At the national level, it divided civil defence headquarters into three main branches — plans and operations, technical services, and training. It made provision to keep the public informed and to maintain intelligence liaison with the armed services. The report proposed civil defence duties for the various federal government departments. A similar organization was proposed for the provinces, although Worthington took great pains not to appear to be dictating to the provincial governments. After discussions with the cabinet secretariat, it was decided that the whole subject of civil defence should be placed before the War Book Committee. In August 1949, Worthington’s recommendations were considered by it.xiii

The recommendations which the Civil Defence Co-ordinator made to the War Book Committee were based upon certain clearly defined principles:

∙ to set up in peacetime the framework of a civil defence organization that could be expanded quickly and efficiently when an emergency threatens;

∙ to take preparatory steps in peacetime on those measures which should be carried out before an emergency exists; and

∙ to determine policy on those measures which would not normally be taken until an emergency threatens.

Worthington sketched out the suggested roles of the three levels of governments. He proposed that the federal government should take the initiative in planning civil defence on a national scale and that it should function as a coordinating agency. To accomplish this end, a Federal Office of Civil Defence should be established to keep civil defence plans under constant review and to advise the Minister on any changes which could become necessary because of strategic developments. The provision and coordination of training for civil defence personnel, the preparation of information for the public, and the provision of liaison officers with the armed forces were also considered to be part of the functions of the Office. In addition, it would be responsible for the coordination of the emergency plans of other government departments and agencies and it would assist the provincial governments in preparing their civil defence plans. It would also assign to the various federal government departments responsibilities for the planning and execution of those civil defence measures which were natural extensions of their normal peacetime functions. The provincial governments would assume the role of area planners and co-ordinators within the scope of the broad national plan. They would also provide those services which were their responsibility in time of peace. The municipalities would direct local planning and, with some assistance from outside, control the execution of civil defence measures.

Civil defence planning would be premised on the assumption that any attack on Canada would be of a diversionary nature, while the main war was being fought in Europe. It was expected, however, that there would be an air attack using high explosives and other conventional weapons directed against large centres and vital industries. To meet this threat, planning for both preventive measures (such as setting up a warning system, consideration of the dispersal of industry, communication facilities, and the building of air raid shelters) and remedial measures (such as fire-fighting, the restoration of devastated areas, and caring for the injured) needed to be in place. The need for an organization planned and trained in advance on a national basis was therefore clear although it was also evident that the actual execution of civil defence measures would have to be decentralized to the greatest possible extent. Therefore close cooperation and coordination among the various levels of government and departments involved in emergency planning was necessary.xiv

The War Book Committee agreed to Worthington’s proposals. Subsequently, it established a sub-committee, chaired by the Civil Defence Co-ordinator, made up of representatives of those federal departments which were to be responsible for aspects of civil defence — initially National Defence, National Health and Welfare, Transport, Trade and Commerce, Reconstruction and Supply, Labour, Finance and the cabinet secretariat. Representatives of the RCMP and other departments were added as the need arose. The overall responsibility of this Co-ordinating Committee was to coordinate the early activities of the civil defence organization. As its immediate task was to study Canadian organizational requirements for civil defence, Worthington and a number of his staff were sent to the Civil Defence Staff College in the United Kingdom to study methods of training and organization. During the latter part of 1949 and the first few months of 1950 a number of projects were initiated. National fire-fighting capacity was evaluated and a program of standardization of equipment was begun. Advisory panels were set up to deal with various technical problems, shelter requirements, disaster relief, and transportation. Preliminary steps were taken towards the establishment of a civil defence training school and the preparation of training literature. The first steps were also taken toward the establishment of provincial civil defence organizations.xv

The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 and the possibility of yet another world war emphasized the need for civil defence. As a result, it was decided to hold a Dominion-Provincial Conference in August 1950 to discuss both what had been accomplished and what had yet to be done. Of particular interest to the provinces was a clear statement of the responsibilities to be assumed by the federal and provincial governments. The delegates agreed that national policy and the coordination of provincial planning must be the responsibility of the federal government. Since civil defence was a national concern, they considered that the costs would also have to be borne in some part by the federal government, largely in the form of grants. Federal officials, they acknowledged, would have the authority to decide on local requirements across the country. The delegates also agreed that the federal government would be responsible for setting up central schools for the training of instructors and leaders, preparing instructional manuals, and providing training materials. The provinces were to ensure the formation of local civil defence organizations, coordinate civil defence plans and training within the provinces, organize mutual aid and reception areas, and provide the necessary legal authority to establish these programs.

With a clear framework established by the conference, the provinces acted quickly. Within six months all ten provinces had nominated ministers to take charge of civil defence and had set up provincial civil defence organizations. Many municipalities were well advanced in their planning and organization, as well. Consequently, a second Dominion-Provincial Conference was held in February 1951 at which the main topic of discussion was the financial responsibility for civil defence training, equipment, and supplies. The federal government agreed to assume responsibility for stockpiling medical supplies, for providing equipment for protection against sabotage, for conducting research and development in civil defence matters, and for providing staff courses and special courses on Atomic/Biological/Chemical (ABC) warfare and other technical matters. The federal government also agreed to establish a warning system in cooperation with the provinces and local authorities; it would supply and install sirens and other warning devices in municipalities having a population over 20,000 and in municipalities forming part of a target area. The conference also considered in detail many technical aspects of civil defence, such as warning, shelters, treatment and hospitalization, evacuation of casualties, maintenance of law and order, restoration of public utilities, and firefighting. Upon conclusion of the conference, a continuing Dominion – Provincial Advisory Committee on Civil Defence was set up, composed of representatives of the federal and provincial governments, to keep these matters under review.xvi

Thus by early 1951, the government of Canada was once again planning to protect its citizens from the effects of war. The initial euphoria at the end of the Second World War had been replaced by the anxieties of the Cold War. This led the federal government to appoint Major General Frederick Worthington as Civil Defence Co-ordinator to advise the Minister of National Defence on civil defence matters. Aware of the experience of ARP during the Second World War and recognizing the jurisdictional and geographical problems of the country, Worthington recommended the creation of a decentralized skeleton civil defence organization. The federal government would plan, coordinate, and, to some extent, finance the effort. The provincial governments would create the provincial organizations and local volunteer agencies would be responsible for implementing the civil defence plans. In August 1950 and in February 1951, two Dominion-Provincial Conferences were held to negotiate the respective responsibilities of the provincial and federal governments. Then the Department of National Health and Welfare was assigned the responsibility of implementing the civil defence policy.

III Civil Defence In the Department of National Health & Welfare 1951-59

1 Governmental Organization

Following the Dominion-Provincial conference of February 1951, the responsibility for civil defence was transferred from the Minister of National Defence to the Minister of National Health and Welfare.xvii At the same time, the responsibilities of the federal and provincial governments were set out more precisely. Civil defence was to be organized within the existing governmental framework, respecting the boundaries of federal-provincial jurisdiction. While civil defence was clearly an aspect of planning for war, it was agreed — apparently at provincial insistence — that the organization could deal with natural disasters as well. Although reluctantly accepted by the federal government, this agreement foreshadowed the shape of things to come.

Under these new circumstances, the federal government undertook to set out an organization plan as a guide for each level of government to follow. It assumed responsibility for coordinating the activity of the various levels of government and for maintaining liaison with the armed forces and the civil defence organizations in the United Kingdom and the United States. It would conduct research, provide training programs, supply equipment (such as training aids, radiation detection devices, respirators, steel helmets, etc.), and give direct financial aid to the provinces and municipalities on a dollar for dollar basis. It agreed to share with the provinces the cost of a compensation program for injury or death of civil defence workers.

For their part, the provincial governments agreed to set up civil defence organizations along the lines set out by the federal government. They undertook to ensure that the municipalities in the urban target areas put in place local organizations. Where necessary, they were to cooperate with the civil defence organizations of the adjacent states. They agreed to assist in training workers by establishing schools or assisting municipalities in their training programs. Equipment issued by the federal government would be distributed through the provincial agencies. They agreed to keep the federal authorities informed of the progress of their programs and to suggest changes or improvements where required.

Major General Worthington, who remained as federal Civil Defence Co-ordinator, was transferred to the Department of National Health and Welfare and directed to work through the Deputy Minister of Welfare. His responsibilities were essentially the same — to advise the Minister and Deputy Minister on civil defence matters, to coordinate federal planning and action, and to maintain liaison with civil defence agencies in the United Kingdom, the United States, and other countries. He was also chairman of the Civil Defence Co-ordinating Committee, an interdepartmental body which had been established previously to oversee civil defence planning in designated federal departments. It had been expanded to include representatives of the departments or Agriculture, Finance, Labour, National Health and Welfare, Public Works, Resources and Development, Trade and Commerce, Transport, the RCMP, and the secretary of the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Representatives of other agencies were brought in as the need arose.

The day to day duties of the Civil Defence Co-ordinator were carried out by the staff of the Civil Defence Division within the Department of National Health and Welfare. It was divided into three sections:

Operations and Training was responsible for developing strategic and tactical operational plans, conducting training at federal schools, and assisting provincial and local schools as required.

Administration and Supply dealt with problems of administration, including relationships with other federal departments and with provincial civil defence authorities. It was responsible also for the procurement of training aids and equipment through the department’s Purchasing and Supply Division.

Other Service Activities included health planning, welfare planning, communications and transport, plant and animal diseases, police matters, research and development, and information services.

A section of the Civil Defence Division, organized in August 1951 to be responsible for developing a program of civil defence preparations for the federal civil service in the Ottawa area, should be noted as a precursor, in part, to the future continuity of government program. Its mandate was to ensure that there would be one organization in each federal building capable of being merged into an organization which the city of Ottawa might form in the event of a civil defence emergency. Over the next six years, over 5000 trained volunteers were enrolled into operational teams throughout federal buildings. In addition, all government buildings in Ottawa were surveyed with respect to shelter plans, means of evacuation, and existing alarm systems. In 1955 the Civil Defence Division was assigned the responsibility for the organization and maintenance of the Fire Warden service and conducting evacuation practice drills in premises owned or occupied by the federal government in the Ottawa area. Subsequently, annual emergency evacuation drills were held in the majority of federal buildings. Attention shifted during 1957 from mass indoctrination towards more specialized training. Rescue, radiation monitoring, first-aid, home nursing, casualty simulation courses, staff indoctrination, and control centre operations, including teletype practice, were undertaken.xviii

During 1954, in response to the growing size and complexity of the civil defence program, the Civil Defence Division was reorganized. It was made up of the following branches and services:

(a) Administration Branch

(b) Training and Operations Branch

(c) Plans Branch

(d) Transportation and Communications Branch

(e) Public Relations

(f) Secretariat

(g) Library and Statistics

(h) Health Services Branch

(i) Welfare Planning Group

(j) Canadian Civil Defence College, Arnpriorxix

Over the next few years as more information became available on the effects of thermonuclear war, the division’s responsibilities expanded. In April 1955, two new sections were authorized: a Planning Section and a Liaison Section. The Planning Section was to assist in the development and rehearsal of evacuation plans for the population of areas threatened by attack. The Liaison Section was to maintain direct contact with provincial civil defence authorities on all matters, but in particular on the Federal Financial Assistance Program and on related planning.xx In January 1956, a Special Weapons Section of the Health Services Branch was set up to study defensive measures against nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons.xxi Late in 1958, the engineering functions of the Plans and Operations Section were transferred to a new Engineering Section. Eventually, this section became involved in the design of a range of bomb shelters for incorporation in all types of buildings and the engineering portion of a shelter/evacuation study.xxii

While the federal government was developing its civil defence organization, the provinces and municipalities were setting up their own parallel organizations. By 1951, each province had created a civil defence organization with a minister responsible for civil defence and a provincial co-ordinator or director. At the time of the transfer of responsibility for Civil Defence, the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario had already conducted civil defence training courses to train local instructors and key municipal personnel. The instructors in these schools had, for the most part, been trained at federal training centres and at federal expense.

At the municipal level, all potential target areas and communities of over 50,000 population (with the exception of Ottawa) had set up civil defence organizations by the end of March 1952. In a number of cities — Halifax, Montreal, Windsor, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Vancouver, and Victoria — local training schools were established. With the exception of Quebec and Prince Edward Island where activity remained at a minimal level, the provinces and most of their important municipalities had made substantial progress by 1955. A total of 554 municipalities possessed some form of a civil defence organization, while 128 had fully developed programs which included included a director, various services, and training facilities. In 1951, 50,000 civil defence workers were enrolled; by 1957 enrollment had increased to 275,319 workers. Of these 248,850 were trained. This group included full-time provincial and civil employees, such as fire, police, utilities, and civil defence personnel, and part-time civilian volunteers. The civil defence organization usually consisted of a number of services — intelligence and information, communications, transport, police, fire, health (medical and welfare), engineer and public utility, rescue, ambulance, and warden. Most of these services already existed in the communities and needed only to be expanded by volunteers in time of a war emergency.

2 Attack Planning

With the advent of the atomic and hydrogen bombs and long range bombers to deliver them, North America lost the immunity from enemy attack that it had enjoyed during two world wars. From 1949 to 1954, however, the Canadian General Staff continued to believe that aerial attacks on North America would be diversionary in character, designed to draw forces away from the main area of attack in western Europe. Under these circumstances, Canada was thought to have three advantages. First, few Canadian cities were likely to be attacked initially since the main targets would be in the United States. Secondly, few centres of dense population were near each other, thus limiting the damage that could be accomplished with a single strike. Thirdly, an excellent transportation service existed to move people or supplies to or from attacked areas. Consequently, civil defence planning was directed toward protecting the public in target areas against a nominal atomic bomb of 20kt. Thirteen cities were classified as target areas: Montréal, Toronto, Ottawa-Hull, Windsor, Niagara Falls, Halifax, Vancouver, Hamilton, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Québec City, Saint John, and Victoria. It was accepted that extensive damage would be inflicted on people and property if any of these cities were hit, but national survival under such an attack was never seriously considered.xxiii

During the early 1950’s Canada was divided into three distinct types of functional areas for civil defence organizational and planning purposes:

TARGET AREAS: These were centres which were considered liable to attack because of population density and industrial importance. The target area consisted of one or a number of adjacent municipalities. In every case the organization was built within the framework of the civic government. Where more than one municipality formed a target area a joint control committee was established. The organization and planning of civil defence for the target area was designed to meet the war emergency within the limits of the area itself.

MUTUAL AID AREAS: These consisted of all the communities surrounding the target area within a distance of 50 to 70 miles. Civil Defence in those areas was organized into a mobile column (to move in and reinforce the target area personnel) and a static group (to accommodate injured and homeless people).

MOBILE SUPPORT AND RECEPTION AREAS: These were composed of municipalities outside the above-mentioned areas. They were organized to act as a general reserve, receiving the overflow of casualties and some priority classes of homeless, and providing certain forms of mobile support in specialist personnel and resources.xxiv

It was not at that time the policy to evacuate large numbers of people. It was thought that they would have to stay and deal with the crisis in the target area and live there after the disaster in order that the war effort would not falter.

In February 1954, the United States Atomic Energy Commission released factual information on the results of a thermonuclear device, a hydrogen bomb, with megaton yield which was exploded in December 1952. Further tests in 1954 disclosed the terrible effects of radiation fallout. As a result of these disclosures the assumptions behind civil defence planning were reassessed and it became gradually apparent that Canada was faced with the problem of national survival. From the start of any Third World War North America must be prepared for attack by nuclear weapons with little warning. Strategists believed that the retaliatory power of the United States Strategic Air Command would ensure that this phase of the war would last a matter of days rather than weeks. However, they also realized that even a few days of nuclear warfare would produce widespread destruction, disrupting communications and public utilities. It was possible that local government would collapse and that public morale would be strained to the breaking point.

The introduction of the hydrogen bomb altered planning assumptions. Well constructed buildings would withstand the blast of an atomic bomb and their basements would give ample shelter except directly under ground zero. A ‘take cover’ policy, however, would be of little use during an attack by the more powerful hydrogen bombs. It was estimated that of a total population of 5 million in the thirteen target cities, 3,500,000 would be killed, 1,250,000 would be injured, and only 250,000 would be uninjured should there be a nuclear war. A stay-put policy was clearly no longer feasible and consideration had to be given to large scale evacuation of the civilian population of urban target areas.

On 28 July 1956, the Honourable Paul Martin, Minister of National Health and Welfare, announced government policy in the House of Commons:

We now believe that our civil defence policy should be based on the development and testing of plans for the orderly evacuation of the main urban areas in our country should the possibility of attack on such areas by nuclear weapons appear to be imminent.xxv

He then went on to name the thirteen cities that had been designated target areas on the advice of the Chief of the General Staff and approved by the Federal Government Civil Defence Policy Committee (see above). This policy was not challenged by any provincial government and there was no disagreement about the chosen Urban Target Areas.

The survival plan which was developed was outlined in “A Guide to Survival Planning”, issued in 1956. The plan involved four phases:

Phase A: Pre-attack evacuation of the non-essential personnel of the Urban Target Areas, based on a strategic warning of 8 to 12 hours;

Phase B: Planned withdrawal of the remaining population of the Urban Target Areas, based on tactical warning of three hours after enemy aircraft are detected on radar screens;

Phase C: Immediate action after a hydrogen bomb burst directed toward the saving of life;

Phase D: Aid and rehabilitation.xxvi

In order to make the plan workable it was necessary to change the civil defence area organization. Instead of three defensive areas, there were now four:

TARGET AREAS – These were expanded to include all the population residing within a 15 mile radius of a probable ground zero.

TARGET SUPPORT AREAS – These included the area lying immediately beyond 25 miles of probable ground zero. The resident population of this area would not evacuate, and it would receive the components of the Target Area Civil Defence forces who would evacuate. Phase ‘C’ operations would be conducted by civil defence forces in the communities of the Target Support Area.

RECEPTION AREAS – These are the areas beyond the boundaries of the Target Support Areas. The habitable parts farthest from the Target Area were reserved for Phase ‘A’ evacuees while those parts closer to the Target Area were reserved for those evacuated during Phase ‘B’. In addition to the reception functions the Reception Area was responsible for organizing Task Groups (composite mobile defence columns) which could be directed to relief or reinforcement in damaged areas.