Webmaster Note: The above piece was written by Mike Braham, a long-time federal emergency planning official and later a dedicated diefenbunker volunteer. The original Document can be found at this link alongwith many others that Mike wrote when he was a volunteer with the Canadian War Museum. (circa 2011).

Mobilisation:

The art of preparing for war or other emergencies through assembling and organising national resources.

The process by which the Armed Forces or part of then are brought to a state of readiness for war or other national emergency. This includes assembling and organising personnel, supplies and material for active military service.

NATO Definition

Background: During the course of World WarII, Canada not only mobilised its Armed Forces on an unprecedented scale, but also mobilised virtually every facet of civilian life and industry in support of both the national military effort and that of the Allied struggle at large.

Canadian industry produced armaments and military equipment of every type, including aircraft, ships, tanks, trucks, artillery, small arms and ammunition of all calibres. This required a massive restructuring of peacetime production lines and the retraining of the workforce, particularly the huge influx of females who filled in brilliantly on the factory floor in place of men who had joined the Armed Forces.

Canada’s vast natural resources were tapped to an extraordinary extent to provide the raw materials for this huge surge in industrial production and the basic foodstuffs, not only to feed Canadians at home and overseas, but also our Allies in Europe who suffered from extreme shortages of food due to the devastation caused by the war.

Canada also provided a safe haven for a huge military training effort, particularly for the hard pressed Commonwealth air forces. The British Commonwealth Air Training Program trained thousands of badly-needed pilots and aircrew at newly constructed airfields all across the country. Vestiges of those sites remain in many small towns as local airfields.

The driving force behind Canada’s outstanding wartime civil mobilisation effort was Clarence Decatur (C.D.) Howe who was appointed Minister of Munitions Supply in 1939 and remained in the post until the end of the war. Commonly referred to as the “Minister of Everything”, Howe coordinated and drove the mobilisation of the nation’s resources.

Following the end of World War II in 1945, there was a general desire to return to a state of normalcy and to redirect Canada’s industrial and human efforts toward a vibrant economy that would improve the standard of living of all Canadians, and one driven by private enterprise with a minimum of government intervention.

As a result civil mobilisation planning within the federal government fell into a state of neglect until the late-1950s.

1957 – 1980

In 1948 a new Civil Defence organisation was established, first under the Department of National Defence and later transferred to National Health and Welfare. The new organisation’s primary role was that of coordinating federal emergency planning.

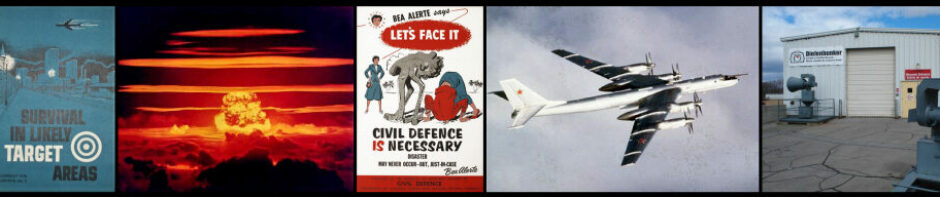

In the face of rising concerns of a nuclear war with the Soviet Union, a second civil emergency planning body was formed under the Privy Council and called the Emergency Measures Organisation (EMO). The focus of the EMO was on war-oriented planning and the continuity of government in the event of nuclear war.

The two separate organisations existed until 1959 when the Civil Defence Branch was dissolved and the EMO was charged with the entire responsibility for coordination of federal planning for civil defence, war mobilisation planning, and for continuity of government planning.

This organisation remained in place until 1974 at which time the EMO was restructured and renamed as the National Emergency Planning Establishment (NEPE). The mandate of NEPE was broader than that of the EMO and, in addition to wartime planning, was charged with plans related to natural and manmade disasters. The name of NEPE was subsequently changed to Emergency Planning Canada (EPC).

The next major change to the emergency planning landscape came in October 1980 with the passage of Emergency Planning Order (P.C. 1981-1305).

National Emergency Agencies (1981-1988)

The Emergency Planning Order (P.C. 1981-1305) assigned specific emergency planning responsibilities to Federal Ministers for both peacetime and wartime emergencies.

With respect to the latter, the EPO called upon federal Ministers to:

- Develop and maintain plans for war emergencies; and,

- Plan for National Emergency Agencies (NEAs) to operate during peacetime emergencies, as well as during war.

In time of war the existence of the War Measures Act would confer sufficient authority upon the federal government to put into effect the required plans and arrangements, including those applicable to NEAs. However, the implementation of NEAs in a peacetime emergency would have required additional Parliamentary approval in the form of new legislation. For that reason, NEA planning focussed almost exclusively on a war emergency.

Eleven National Emergency Agencies were identified and are depicted in the following Table along with the responsible Minister and, in some cases, a collateral Minister.

| National Emergency Agency (Abbreviation) | Responsible Minister 1 (Collateral Minister) |

| Food (NEAFood) | Agriculture (Fisheries and Oceans) |

| Telecommunications (NEAT) | Communications |

| Manpower (later Human Resources) NEAHR | Employment and Immigration (Labour) |

| Energy (NEAE) | Energy, Mines & Resources |

| Financial Control (NEAFin) | Finance |

| Health & Welfare Services (NEAHWS) | Health & Welfare |

| Industrial Production (NEAIP) | Industry, Science & Technology (Supply and Services) |

| Public Information (NEAPI) | Prime Minister (Emergency Planning Canada) |

| Construction (NECA) | Public Works |

| Housing & Accommodation (NEAHA) | Canada Mortgage & Housing |

| Transportation (NEATran) | Transport |

Table 1

These National Emergency Agencies were intended, where applicable, to include the participation of Provinces, municipalities and the private sector. When activated, they would, “control and manage … control and regulate … the resources of the nation”. They were therefore meant to possess sweeping powers in the event of a national emergency. For this reason, the NEA concept was not embraced very enthusiastically by the Provinces who viewed them as federal intrusions into provincial constitutional mandates.

The planning effort was coordinated by Emergency Planning Canada (later Emergency Preparedness Canada) by means of a Committee structure chaired by EPC at the Executive and Working levels.

As a member of NATO, it was essential that Canadian national war planning be conducted with due regard to the broader Alliance planning effort. For that reason, there was a close correlation between the NEAs and the NATO Planning Board/Committee structure and Canadian NEA planners represented Canada on those bodies as shown in Table 2.

| NATO Planning Board or Committee | Canadian Departmental Representative |

| Senior Civil Emergency Planning Committee (SCEPC) | Emergency Planning Canada |

| Civil Communications Planning Committee (CCPC) | Department of Communications |

| Petroleum Planning Committee (PPC) | Energy, Mines & Resources |

| Food & Agriculture Planning Committee (FAPC) | Agriculture Canada |

| Industrial Planning Committee (IPC) | Industry, Science & Technology |

| Planning Board on Ocean Shipping (PBOS) | Transport Canada (Marine) |

| Civil Aviation Planning Committee (CAPC) | Transport Canada (Air) |

| Civil Defence Committee (CDC) | Emergency Preparedness Canada |

Table 2

Of equal importance was the requirement to develop a close cooperation with the United States emergency planning community. A bilateral agreement had first been signed between the two countries during WW II and, in 1986 was reaffirmed by the signing of, “The Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States of America on Co-Operation in Comprehensive Civil Emergency Planning and Management” by the Heads of Emergency Preparedness Canada and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

This agreement, based on ten governing principles, pledged the two countries to remove impediments to cross-border cooperation in emergency preparedness and response. Under the oversight of a high-level Consultative Group that met annually, a group of bilateral Working Groups were established to improve capabilities within their particular spheres of interest. The CA/US Committee structure is depicted in Table 3.

| Committee | Lead Department |

| CA/US Consultative Group | Emergency Preparedness Canada |

| Transportation Working Group Railway Sub-Group | Transport Canada Transport Canada (Surface) |

| Health Services Working Group Nuclear Emergency Sub-Group | Health & Welfare Canada Health and Welfare Canada (BRDM) |

| Telecommunications Working Group | Department of Communications |

| Agri-Food Working Group | Agriculture Canada |

| Exercise Working Group | Emergency Preparedness Canada |

Table 3

Supported by this impressive array of national and international committees, the development of National Emergency Agencies proceeded rather unevenly until the passage of new federal emergency legislation in 1988.

Several Departments took their responsibilities for NEAs very seriously and developed comprehensive plans and arrangements. In the forefront were the NEAs for Energy, Telecommunications, Transportation, Agri-Food, and Housing. Good progress was also made in the ever-changing area of Human Resources. Little was achieved, however, in the fields of Finance, Industry and Construction.

National Emergency Arrangements – Post 1988

Not specifically related to National Emergency Agencies per se, but rather to the potential for excesses under the War Measures Act, increased public pressure convinced the government of the day that new, comprehensive federal emergency legislation was needed. This led to the passage, in 1988, of two new pieces of legislation – The Emergency Preparedness Act which charged all Ministers of the Crown with developing emergency plans within their mandated areas; and, the Emergencies Act which defined a “national emergency” identified four types of national emergency; and carefully prescribed the provision of governmental powers under close Parliamentary supervision, for each type. The Emergencies Act replaced the War Measures Act.

There was no specific reference to National Emergency Agencies in the new legislation and several Departments saw this as an opportunity to cease plans in that regard and to adopt a more broadly based “all hazards” national emergency arrangements approach.

Several sectors, however, continued to embrace the NEA concept as part of their range of national emergency arrangements. As a rule, these NEA components were only applicable in the context of International or War Emergencies as defined in the Emergencies Act.

This broader based planning, with stronger support from the Provinces helped to stimulate national emergency planning and, in addition to the National Emergency Agency plans already in place and retained, led to a number of crisis-specific and generic national emergency arrangements as indicated in Table 4.

| Plan or Arrangement | Lead Department |

| Federal Nuclear Emergency Response Plan (FNERP) | Health & Welfare Canada |

| National Earthquake Support Plan (NESP) | Emergency Preparedness Canada |

| National Counter-Terrorism Plan (NCTP) | Solicitor General |

| Food and Agriculture Emergency Response System (FAERS) | Agriculture Canada |

| Energy Supplies Allocation Board (ESAB) | Energy, Mines & Resources |

| National Support Plan (NSP) | Emergency Preparedness Canada |

Table 4

Conclusion

The development of National Emergency Agencies in Canada was stimulated by the fear of a nuclear war and based upon the civil mobilisation experience of the Second World War. However, there was little enthusiasm for such planning in a country tired of war and trying to return to a state of normalcy. Within the constitutional framework of Canada, National Emergency Agencies were viewed with suspicion and distrust by the Provinces who viewed them as a Federal intrusion into their domains of responsibility.

As a result, the life of NEAs as a viable emergency planning and response concept was relatively short (1981-1988). Nonetheless, their development, albeit uneven among the participating departments, established a basic emergency planning discipline that provided a strong basis for the more broadly based and politically acceptable national emergency arrangement planning that followed and which continues to be practiced today.

These are the Department names at the time. Most have since changed.