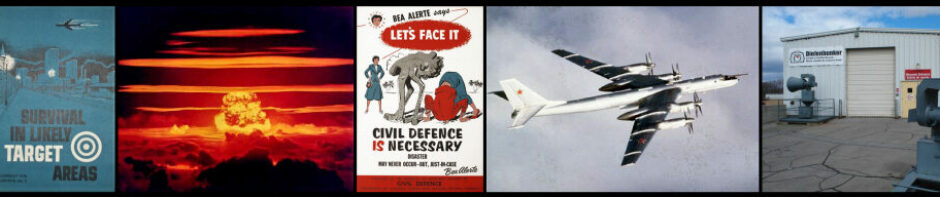

During the Cold War (1947 to 1991) Canada participated in 12 United Nations peacekeeping operations……………………..

To summarize the Canadian experience here is an article (Canada and the Cold War) from the Canadian Encyclopedia written by Historian J.L. Granatstein (a fellow of the Canadian Defence and Foreign Affairs Institute) which captures the Canadian Peacekeeping experience very nicely. ‘Jack’ (as the then head of the Canadian War Museum) was a real friend of the Diefenbunker during our formative in becoming a Museum of the Cold War, especially in assisting us with advice and getting ‘stuff’ to help ‘dress’ the Museum’s displays. (DND had pretty much stripped the building of its F&E as they were intending to seal it with concrete as they had done the associated Richardson TX site July 1997).

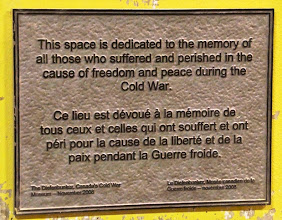

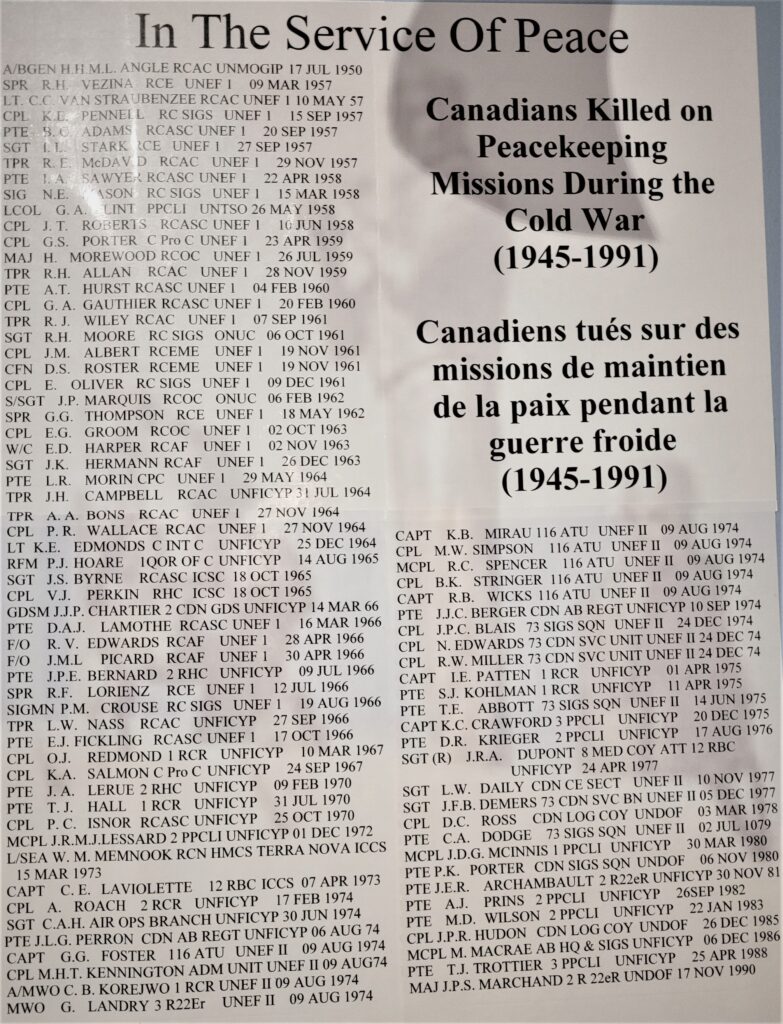

First take a look at this plaque. According to the above Granatstein article about 125 000 Canadians have served on peacekeeping missions of which about 130 have died on duty.

………….We have a duty to remember them …………………….

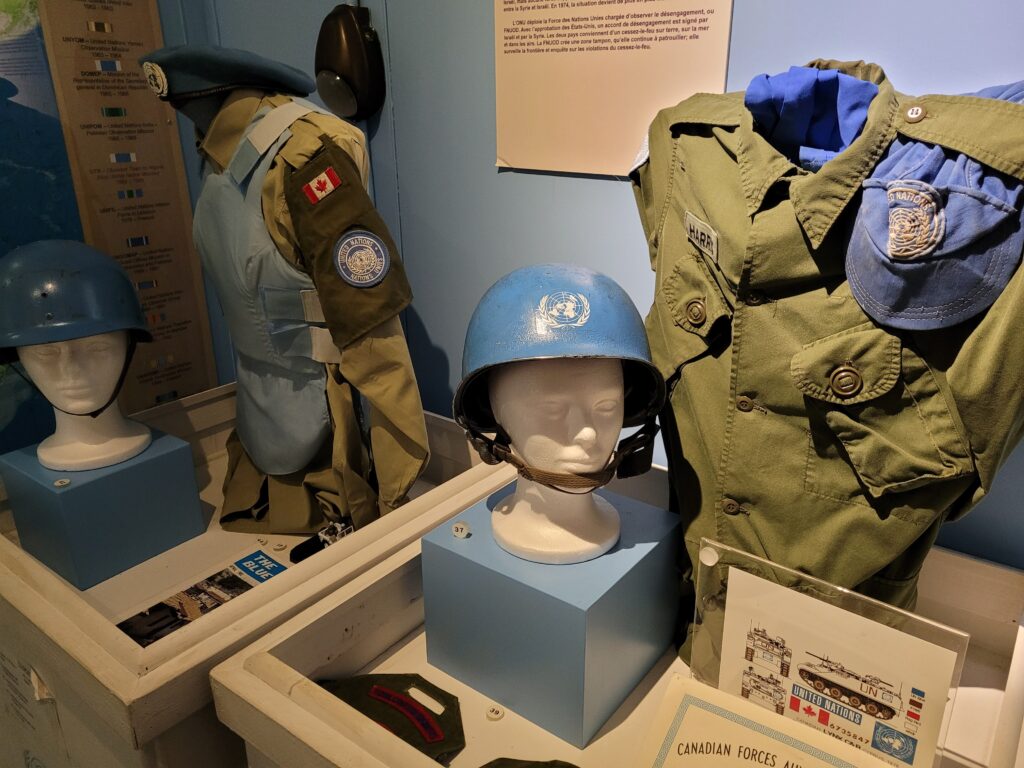

The Peacekeeping Exhibit at the Diefenbunker (2011 to 2020)

In remembrance of this important part of what Canada did during the Cold War, in 2011 I got permission from the bunker’s Board of Directors to construct an exhibit on Canadian Peacekeeping in the Diefenbunker, CCWM. I was largely responsible for the design and actualization of this exhibit. Having been on such a mission I felt reasonably qualified to do this. Fortunately I still had military friends who had participated in many of the peacekeeping missions Canada had been involved with since the original UNEF mission and I was able to persuade them to lend some of their souvenirs for this Peacekeeping exhibit. I was able construct this exhibit fairly inexpensively by using some of the surplus exhibits cases that the museum had acquired over the years…the rest I paid for out of my own pocket. This exhibit was closed by the bunker staff in late fall 2021. The above (albeit) crude poster is still mounted on the wall in that room. (I was recently was able to take a picture of it.)

Note: Not all peacekeeping mission that Canada undertook were under the auspices of the UN. The ICCS South Viet Nam 1973 (see the picture on the left above and the text below) is an example.

The International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS) was organized along the same lines as its largely ineffective predecessor, the ICSC. With the withdrawal of the United States from Vietnam, the United States had asked Canada to participate in the (new) International Commission for Control and Supervision (ICCS). Canada agreed, on the condition that Canada could withdraw if the ICCS proved to be non-effective. (which happened in July 1973). A ceasefire had gone into effect a few days before the Canadian delegation had arrived in January 1973. The Canadians held the senior appointments in administration, communications,transportation and investigation of prisoner exchanges. Mobile and site teams were set up in South Viet Nam’s controlled ports of entry with some teams set up in Viet Cong stronghold areas. The observer often found themselves under heavy fire. In 1974 after the targeted killing of some ICCS members Canadians withdrew from Viet Nam. Two military and one diplomat Canadians were killed during this mission.

******************************************************************************

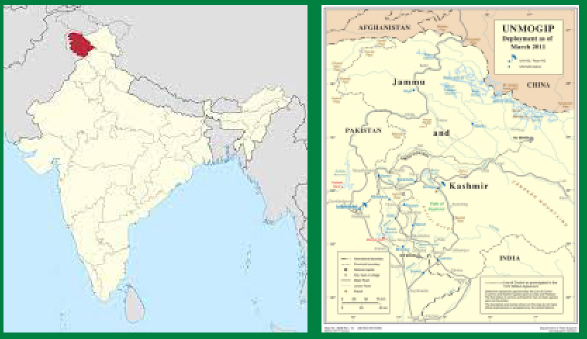

UNMOGIP (and Dave Peters Personal Experience as an ‘UNMO’ in Kashmir in 1973)

“The first group of United Nations military observers arrived in the Indian sub continent mission area on 24 January of 1949 to supervise the ceasefire between India and Pakistan in the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Following renewed hostilities of 1971, the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) has remained in the area to observe developments pertaining to the strict observance of the ceasefire of 17 December 1971 and report thereon to the Secretary-General.”

The following narrative and images will highlight my own personal story about my year on the Indian Subcontinent with the United Nations Military Observer group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP). Subsequently I will include some information about other Canadian UN Peacekeeping Missions as I research them more thoroughly

Some images from my UNMO service with UNMOGIP in 1973.

Late in 1972 I was told that I had (unknown to me) been selected to serve for the year of 1973 with the United Nation Observer Group in India/ Pakistan. I had never heard of it before. At the time I had just two years previously graduated from the Royal Military College of Science in the UK and had been promoted Major. I was serving as an engineer equipment staff officer at National Defence HQ in Ottawa. This UN posting, literally “out-of-(and into)-the-blue”was quite a surprise for me as I had just arranged to take a military sponsored post-graduate Environmental Engineering Degree at Waterloo…plus late October my wife and I had just purchased and moved into a new house (there wasn’t even any grass!). The last minute nature of this posting was due to the originally posted fellow military engineer having found a reason not to go. (Maybe he didn’t like heat, humidity, snakes, foot-long centipedes and spicy food…who knows?)

Fortunately the Army doesn’t put one in these situations without at least some preparation so I had a five day training course on the ins-and-outs of the mission, it’s somewhat checkered history, and all the subcontinent’s potential political, religious and cultural ‘baggage’, i.e.,things that could go wrong! There was even a short lecture about what I was actually supposed to do while there. In the few weeks before departure I had some time-off from my NDHQ staff job to prepare myself and my long suffering, wonderful military wife for the coming year’s absence and to get ready to travel to the posting in Kashmir. The following extract from a UN website summarizes what the mission was all about at the time of my posting to UNMOGIP:

————————————————————————————————————

- UNMOGIP’s functions were to observe and report, investigate complaints of ceasefire violations and submit its findings to each party and to the Secretary-General. At the end of 1971, hostilities broke out again between India and Pakistan. When a ceasefire came into effect on 17 December 1971, a number of positions on both sides of the 1949 ceasefire line had changed hands. The UN Security Council met and on 21 Decem

- ber adopted resolution 307 (1971), by which it demanded that a durable ceasefire in all areas of conflict remain in effect until all armed forces had withdrawn to their respective territories and to positions which fully respected the ceasefire line in Jammu and Kashmir supervised by UNMOGIP

- .In July 1972, India and Pakistan signed an agreement defining a Line of Control in Kashmir which, with minor deviations, followed the same course as the ceasefire line established by the Karachi Agreement in 1949.

- India took the position that the mandate of UNMOGIP had lapsed, since it related specifically to the ceasefire line under the Karachi Agreement.

- Pakistan, however, did not accept this position. Given the disagreement between the two parties over UNMOGIP’s mandate and functions, the Secretary-General’s position has been that UNMOGIP could be terminated only by a decision of the Security Council. In the absence of such an agreement, UNMOGIP has been maintained with the same arrangements as established following the December 1971 ceasefire. The last report of the Secretary-General to the Security Council on UNMOGIP was published in 1972.

- Since the Simla Agreement of 1972, India has adopted a non-recognition policy towards third parties in their bilateral exchanges with Pakistan over the question regarding the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The military authorities of Pakistan have continued to lodge alleged ceasefire violations complaints with UNMOGIP. The military authorities of India have lodged no complaints since January 1972 limiting the activities of the UN observers on the Indian-administered side of the Line of Control, though they continue to provide necessary security, transport and other services to UNMOGIP.

———————————————————————————————————–

It appeared that the job was to supervise the cease-fire agreement(s) between the Indians and Pakistanis in the disputed area of Kashmir located on the NW frontier. Both of these parties were armed to the teeth, professional militarys who had been at each others throats since the British partitioned the subcontinent in 1949. Fortunately I had my five days of familiarization training to prepare me for this UN Observer assignment! The area had recently been fought over during the 1971 war between India and Pakistan (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pakistani_War_of_1971). Post this war UNMOs were to ‘supervise’ the newly reestablished Line of Control.

Given that it was still virtually a war zone it was somewhat unnerving that no protective gear such as helmets, ‘flac’ jackets, or self defence weapons were provided for the Observers. I suppose it was considered that white jeeps, blue berets, UN shoulder flashes and a UN flag (along with an authoritative demeanor) would be enough to protect us during our inspection tours and other interactions. Oddly, it seemed to work as I felt perfectly safe on most occasions and during most liaison with the local military authorities mainly due to the professionalism of the Indian and Pakistani Army Officers and Senior NCOs. The CMO (Chief Military Observer) was a Chilean General (MGen Luis Tassara). He ran a tight by-the-book operation but considering the backgrounds and variety of officers posted to the 11 country mission, this approach was probably quite necessary (and was a fit with his nation’s – at that time- military ‘philosophy’).

The 11 different nations participating in the military observing operations of UNMOGIP during my time there in 1973 included Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Uruguay, Chili, Finland, Belgium and Canada. Fortunately the common operating language of the Mission was English (which of course most of the Pakistani and Indian officers we interacted with were very fluent in). There was also a permanent staff of UN civilian field officers who “supported” (supply, finance and admin paper work, transport, etc.) UNMOs activities. Frankly some of these folks were more supportive than others.

I left Ottawa just after our first Christmas in our new (and yet to be landscaped) house in Manotick, Ontario. After a ‘rest day’ stopover in each of London and Athens I arrived in Karachi. From there it was a short flight to Rawalpindi. There I got a few days briefings at the UNHQ and began acclimatizing including celebrating the (1973) New Year at the Intercontinental Hotel with some other Military Observers and those who had their families with them. It was fun meeting them but it took some time to realize that even though the language of the mission was English for many them it was not their primary language.

It was about this time that I also discovered that ALL of the 11 nations sending observers (EXCEPT Canada) encouraged the families of observers to accompany their husbands (they even subsidized the travel and accommodation of these families). These families stayed in the (very safe) UN HQ areas, traveling in the UN Convoy to Srinagar in the ‘summer’ and to Islamabad/Rawalpindi in the ‘winter’. It was somewhat annoying to find this out and I must point out that some Canadian Observers actually brought their families at their own expense. While in the Canadian ‘correct speak’ reason was safety, in reality it was DND being ‘cheap’. However the CF were helpful in other ways (to be discussed late).

I was still not fully over the ten hour time change and the culture shock of being in a sub continent nation, when I was flown in the UN Twin Otter (fondly known to all as “801”) out to my first field station in Jammu, India. This aircraft was supplied by Canada complete with crew and maintenance techs and was a vital link in supporting UNMOGIP, including bringing in our monthly food orders and beer supply (more on this later).

(Note: Please copy and paste the following URLs to access two articles summarizing the ” RCAF support of UN Operations” : http://www.115atu.ca/air-2ot. AND htm & http://www.115atu.ca/ind.htm)

The OIC of the Jammu Field Station was a Swedish LCol. Nice guy but a hard drinker and inveterate jogger. There were two other observers on station, another Swede and a Norwegian. We had a lot of time on our hands because as a result of the recent 1971 war and the resulting Simla Cease Fire Agreement (see above) the Indian Army didn’t permit us to do our observer job of visiting their battle positions to ensure they were in accord with the original Karachi Agreement. We could and did make liaison visits to the local Indian Army offices. They were very polite and friendly but we were just not allowed to do our observing / inspecting job. We were virtually there as tourists!

We did continue to report to UNMOGIP HQ at every evening’s radio check-in ‘sched’ but ‘nothing-to-report’ became a standard SITREP item. We fortunately sometimes socialized with the Indian Army officer’s and their families and were invited to some of their homes for meals and conversations, a wonderful experience. To fill in the time many of us learned (or re-learned) to play squash and had a lot of practice doing this (getting quite serious at times). Evenings were spent playing cards and doing some serious drinking. ‘Hearts’ was the preferred game as it didn’t involve too much deep thinking and thus it wouldn’t interfere with the drinking part. A bottle of Black Label was about three dollars and of course no water or ice was added (that could have led to the feared ‘Delhi Belly’). By having casual conversations with locals (especially by talking to the tailors serving the Indian officers) we were able to come up with a reasonable estimate of the Indian Army Order of Battle in our area as well putting together reasonably clear ideas of various unit’s locations, personnel and equipment strengths and even morale. This information we duly reported (by sealed diplomatic pouches) to our UN HQ where I doubt that it was treated with much importance. We never got any feedback so who knows! The big disappointment in all of this was that, by not being able to visit the Indian battle positions, we missed out on seeing some beautiful local scenery (and probably meeting some very interesting local people). Thus much of our time was taken up visiting local Indian Army offices, playing squash and of course, shopping. Oh and getting over the occasional bout Delhi Belly

I did have one very different and unexpected experience while at Jammu. Somehow I was ‘selected’ to represent UNMOGIP at the January 26th Indian Republic Day Parade in New Dehli. As a UN representative I was seated in the front row of the diplomat’s reviewing stand with a great view of the parade’s marching band and military contingents. This huge parade is one of the most important events of the annual Republic Day celebrations. As a young Canadian Army Major at the time I have to admit to being honored but quite awed by the whole thing . However I ‘faked’ knowing what I was doing and pulled it off successfully (I think!). This YouTube video is relevant

After three months at Jammu in accordance with the ‘normal’ mission rotation policy I was posted to the UN Field Station Sialkot in Pakistan for my next tour of three months. This was not a very exciting trip as it was just about 21 kms west of Jammu a short ‘down-the-road’ trip to the other side of the border with India. The OIC of this station was a Danish Infantry Major and the other observer at the time was a Belgium Artillery Captain. The station was in a residential building and located in the suburbs of Sialkot just across Kahlid Road from the well known and very well cared for Anglican Cathedral. (Holy Trinity -Consecrated in 1857). Visiting this building I was struck by the many memorial stone plaques embedded in its walls and particularly by the number of very young women and children (dependents of the British solders stationed in the Sialkot Cantonment). Imagine leaving your home in Briton in the mid 1800s and journeying to this far off (and to them very foreign place).

The station had very nice, modern (relatively speaking) quarters (and fortunately a window air conditioner in the downstairs living room – the monsoon was about to begin and we all became very thankful for a place to get out of the heat and humidity -if just for short periods. There were very few Pakistani battle positions nearby so much of our time was spent (as it had also been in Jammu) escorting UN and VIPs back and forth across the border (and as usual playing squash , visiting with locals and …shopping for some pretty cool stuff).

Since Sialkot was (at the time) a significant manufacturer of sports equipment, stainless flatware, custom made silver pieces and hand-carved and hand painted crests and plaques we observers made good us of our spare time for shopping (and at the same time getting to know the locals better). In fact sometimes the local merchants graciously invited us to dine at their homes. For those of us not familiar with Muslim customs this was a fascinating cultural experience (and they were very tolerant of our inadvertent ‘faux pas’. There was also a young Belgium family (Dr.and Joce DeWit) working at a medical clinic sponsored by a religious (missionary?) organization living in Sialkot who used to visit us (they had a young baby and we had some air conditioning) at the Field Station from time-to-time and I remember they had us to their place for an excellent meal. (It was there that I learned how to make mayonnaise with a fork and a lot of patience!). The DeWits visited us in Canada in the late 70s and we have kept in touch of-and-on over the decades since.

STAY TUNED….MORE to COME….