Note: The following narrative is my response to a series of good questions asked by Alexander Badzak, the bunker museum’s first professional Executive Director.

Background Information

The first thing to keep in mind is that the CEGHQ was not the place from which the Canadian Forces would have controlled its battle operations (air, land or sea). That would have been done from another location (probably at that time Petewawa). Notwithstanding CFS Carp being a military base it was primarily designed as a facility for Continuity of Government and associated civil defence activities. The military were there to operate the telecommunications, provide nuclear technical expertise, run the building’s administrative support and utilities and provide a limited degree of security and protection.

Secondly there are many changes that took place in roles, function and operational methods in the bunker between its construction and commissioning in the early 60s and its closing in 1994. Initially (in the early/mid 60s) it was supposed to be the primary location for federal Continuity of Government (GoG) operations and the Canadian focus for Federal Warning and emergency civil defence operations. I say supposed to be, because while there was a flurry of preparations for a potential massive nuclear attack on North America following the build-up of nuclear weaponry by both sides, growing public knowledge and concern about the effects of nuclear weapons and the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis of the early/mid 60s, the late 60s and much of the 70s saw the whole civil defence panoply of arrangements become quite dormant.

The threat was still there. In fact it was changing and growing. Initially (during the first years of the bunker’s existence) the threat was primarily from manned bombers such as the Soviet Bear and Bison, As time progressed the threat from a range of Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles became more important. While these ICBMs had smaller nuclear payloads they were much more accurate thus rendering hardened shelters increasingly obsolescent.

However increasing international activity toward banning nuclear tests, some mixed success efforts at detente, along with the impact of the peace movement, reaction to the Vietnam War and many other distracting and seemingly more important happenings led to an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ approach by Canadian Governments and the Canadian Public. This attitude became especially prevalent as a result of the 1968 (Trudeau) Cabinet decision directing that all expenditures of capital funds for Civil Defence be deferred. (Deferment is the means by which government effectively neutralizes a program without actually killing it so that if their decision is wrong they can’t be fully blamed for the consequences!) .

CoG activity just about ceased to exist. Civil Defence preparations ( CoG facilities, Warning Systems, Shelter Programs, Health and Welfare Arrangements, National Survival Preparations, Public Information Programs, the Vital Points Program, etc.) were widely neglected despite being clearly authorised and delineated in various government policy documents (Emergency Planning Orders, the War Book, etc.). A few (very few!) dedicated public servants attempted to keep relevant programs alive. This despite the mood among most senior government (including elected) officials which was to just ignore these aspects of their responsibilities because they felt the whole thing was a waste of time. The common belief was that nobody was going to survive a nuclear war anyway so why bother.

Consequently from the mid/late 60s until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and President Ragan’s push to upgrade the US’s (and NATO’s) military capabilities in the late 70s/early 80s, very little Civil Defence/CoG activity took place at the Carp bunker (or at any other of the bunkers in the system). The only thing that saved the spectrum of Canadian civil defence arrangements from being completely canned was the existence of an ever growing Soviet military strength and pressure from our NATO partners. Also the Trudeau Cabinet’s direction to cease capital expenditures on civil defence (wisely) included a small but important caveat, instructing that all existing civil defence capabilities were to be maintained such that the “… the reduction of emphasis to be placed on these (civil defense) measures… should not result in their being (changed)… beyond a point which would permit their rapid restoration to full operational readiness in a matter of hours or a few days.” In any case the military had already made the decision to move the Federal Warning Centre to its North Bay NORAD facility (for inexplicable reasons) which they did in 1969 while they continued to maintain the Provincial Warning Centres in the REGHQs (and the complely unprotected, above ground (I)REGHQs). During that time period the bunker’s sole task became military telecommunications. Up until the early/mid 70s the equipment performing this task was the Strategic Radio System (STRAD) which occupied virtually the whole of the back area of the 400 level. This included an encryption capability.

In the mid to late 70s the Ottawa Semi-Automatic Exchange (OSAX) was constructed on level 300 (and the bedrooms and offices so displaced were relocated to the 400 level). I don’t believe OSAX was intended to be a direct replacement for the STRAD. As I understand it was tied into another system called SAMPSON which (probably among other things was a system dealing with highly automated logistic support. It appears to have been a classified telecommunication capability the precise purpose of which has never been completely clear to me. We believe that it had a close working relationship with the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), but that organization had very little do (directly) with CoG and civil defense. Sure I think they could have communicated to and from SOME of the REGHQs but I don’t believe that was their primary role. I suggest that CFS Carp was just a convenient, in-place (protected/secure) facility for this telecommunications capability. More research required here but probably much info still classified. Gord may know more but he may still be constrained by the Official Secrets Act.

With the Cold War getting hotter in the early 80s the necessity (and opportunity) to resurrect and to renovate the CoG Program and to reinvigorate civil defense preparations assumed a new importance. For the CEGHQ this meant that Emergency Preparedness Canada (the successor to the Canada’s-civil defense-Emergency Measures Organization) began to reassert itself in the bunker. The former FWC space had already be redesignated as the Military Information Centre (MIC). (Even though the DND moved the FWC back to Carp from North Bay it was decided to retain the MIC name for the room.) EPC officials (myself included-I had been hired in May of 83 as Director of Emergency Operations Coordination) began to pressure the military to move out of the offices and rooms that were actually designated for CoG purposes so that we could get on with our readiness activities.

We formed a interdepartmental committee (the CEGHQ Activation Committee) which met regularly to plan for CoG. We got many of the rooms, procedures and equipment into shape so that they would be ready if called upon. We exercised many aspects of CoG on a regular basis. After the end of the Cold War all of these arrangements were first put on hold and then cancelled in their entirety. FYI the Public Safety folks have similarly purposed plans now but as far as I know they are completely different.

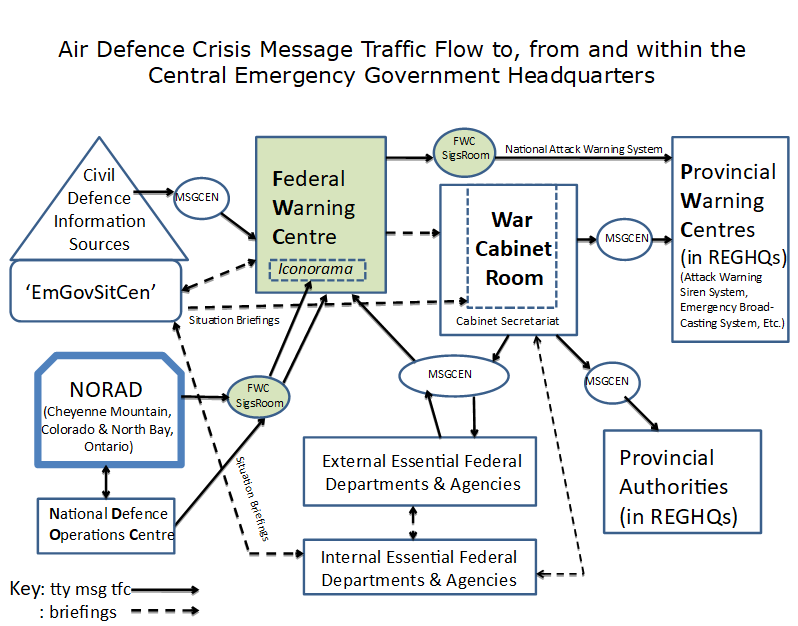

With above as background, the flow of information to, within and from the CEGHQ in the 60s would have looked something like the diagram at fig 1. It looks complicated but it really isn’t. In the following narrative I’ll break it down by locations and responsibilities:

As I alluded to above, in the 70s the info flow would have theoretically been similar. However with the FWC located in the North Bay bunker the attack info would have come in from NDOC. Actually I don’t know how things would have functioned in reality, what with the advisers and civil experts not present to support the FWO and little or no feedback from other sources, especially civil defence authorities. In the 80s with the FWC returning to Carp, some of the attack warning functionality was restored but the EmGovSitCen took on a more active analysis and briefing role.

The following concentrates on the CEGHQ as it was designed and intended to function in the 60s. Please refer to the following diagram to aid in understanding the flow of info.

NORAD HQ(s)

- From intelligence and radar-based info NORAD would send collated ongoing attack info to various HQs including Carp. (FYI – some of the other locations would have included the main US CoG facility at Mt. Weather, Virginia, and the special facility for the US Congress and the Senate at Greenbrier – among probably many others!).

National Defence Operations Centre (NDOC)

- A parallel channel would have seen similar information being sent to NDOC in the National Defence HQ from where it would have been passed (as required) to the CEGHQ’s FWC.

FWC Signals Room

- This information would have been received by the teletypes in the FWC Signals Room (via either the Emergency Radios Room or land line possibly through STRAD, probably but not necessarily encrypted).

- Copies and/or originals of all punched tapes/message forms would have been kept in the Signals Room.

- The room would also have disseminated warning information status and decisions to various locations including (and most importantly) the REGHQs/the provinces, and to our US CoG/NORAD and NATO partners.

- It may also have passed on such info directly to certain designated offsite federal departments and agencies,

FWC Plotting Room

- The punched tape or message form information provided by the FWC Signals Room would have been used to produce Iconorama images for projection onto the FWC Display Room screen.

- The plotting room would have kept an on-going record of the plots as they were updated.

FWC Display Room

- On the top row of the theatre seating would have sat three fairly important individuals (the details of this are informed deduction on my part):

-The Federal Warning Officer (FWO), probably an Army Lieutenant Colonel (LCol). (During this period in the history of civil defence in Canada the government of Canada had given the responsibility for National Survival planning and operations to the Army because only they had the resources, command and control, and organisation to do the job). The FWO’s job would have been to decide when and where to sound the Attack Warning Sirens, when and where to order evacuations or issue stay-put instructions, when to activate the Emergency Broadcasting System, provision of initial information (such as NUDET and contamination areas) to Re-entry Columns, etc.

-The Head of Canada EMO (civil defence), a high ranking public servant (Director-General) whose job it would have been to advise and counsel the FWO on CD matters.

-A representative of Cabinet (Minister or designated Deputy Minister) to input to (and possibly override) decisions of the FWO. This person also would have kept Cabinet informed of the attack/warning situation.

-Also adjacent to the top row (left) would have been a plotting table graphically recording the attack situation.

- The second row of the theatre seating was reserved for expert advisors, assessors and analysts

- The third and forth rows were available for various observers, both military and civilian. It is likely that representatives from some of the federal departments and agencies along with officials from the Cabinet Secretariat and the Civil Defence Info Centre

- There was a table located to the left of the bottom row which was probably intended for a recording clerk.

Civil Defence Information Centre (currently the EmGovSitCen)

- Kept track of the status of the various civilian and military alerts and warning systems.

- Kept track of the readiness/availability status of all CoG emergency government facilities and provincial civil defence HQs across the country

- Received NUDET information from the FWC and uses it to calculate damage and casualty data, and fallout patterns.

- Received actual radioactive fallout ground contamination data (through the RADEF system’s Radiological Scientific and Radiological Defense Officers) and records it graphically.

- Received meteorological information (and incorporates it into its calculations and briefing).

- Provided regular and special situation briefings to the Cabinet and to other parties in the CEGHQ including Ministers, and federal departments and agencies.

- Collected, summarised and briefed Cabinet and other federal departments and agencies on the overall impacts of an attack on the national infrastructure.

- Was reconfigured/updated in the early/mid 80s (and renamed the EmGovSitCen).

STRAD/OSAX

- To the best of my understanding of their operational roles, these telecommunications systems were only important because they were able to handle very high amount of (basically teletype) message traffic to and from a number of nodes across the country and internationally. They were compilers, routers and switchers that were able to handle encrypted and non-encrypted information fast and accurately

- In my role as Director of Emergency Operations Coordination and thus the person in-charge of the Government Situation Centre (peacetime/normal emergencies/disasters located in downtown Ottawa) and at the Carp CEGHQ facility responsible for the EmGovSitCen, I didn’t concern myself with how these capabilities worked-I was only interested in the information they could throughput to and from my area.

Message Control Centre (MCC)

- This facility (located adjacent to what was originally the encryption area of the STRAD) was primarily intended to control message traffic to and from external locations. Of course in the 60s, 70s (even into the early 80s) there was no internet/email nor was there significant facsimile traffic. Messages were written (usually typed) on message forms and taken to the MCC where routing information, encryption requirements and other such requirements were verified before they were sent for onward transmission.

- Staff from federal departments/agency groups, the Cabinet Secretariat, the CD Sitcen and others would have brought their messages to the reception counter (which for some reason was blocked in by the military – probably during the 70s when the STRAD was decommissioned – it should be reopened for tour purposes). Likewise they would have received written messages through the MCC.

- Note that the FWC would NOT have used the MCC for attack warning purposes. It was too slow for that purpose. That is why they had the FWC Signals Room capability.

- Note also that there many other telecommunication ‘drops’ to specific organisations that would have operated from the bunker. For example I believe that the RCMP had a CNCP teletype which was tied into the Canadian Police Information System (CPIS). (one of our overhead projection slide depicts over a dozen of these ‘drops’.

Cabinet Secretariat

- The group of officials would have coordinated government operations particularly those taking place as a result of Cabinet decisions (see fig.2).

- They would have been composed of mid to senior level public servant from the Privy Council Office (PCO) and from the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS). Latterly they might even have had some representation from the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). I say latterly because that is a relatively new institution.

- They would have had very little direct involvement with military operations other than from civil support aspects.

Federal Departments and Agencies

- It was a common misunderstanding that the various federal departments and agencies located in the CEGHQ would have run their organisations from the bunker. Given the size and complexity of such operations this would have been impossible. The small numbers of officials in each departmental/agency team would not have permitted this. Unfortunately this commonly held misconception resulted in a credibility problem (about the viability for the whole CoG Program) in the minds of many of the less involved officials. We were constantly have to correct this so that we could get on with our planning of CoG arrangements.

- The job of the departmental staff in the bunker was to analyse the impact of the attack in their areas of responsibility and to provide information and advice to Cabinet and other organisations as needed. They would have used their particular knowledge and expertise in concert with the information stored or brought to the bunker and that provided from the Civil Situation Centre (EmGovSitCen) and other relevant sources to do this.

- While ‘not my part of the ship’ I had to assume that departments and agencies would have made arrangements for their operations to continue in ‘safe areas’! (Very’fuzzy’ area of the arrangements).

Provincial Offices and Officials

- A limited number of politically high-level political and provincial public service experts and other officials would have been located in the REGHQs and these would also have been the recipients of appropriate information and direction from the CEGHQ.

- Other provincial offices (ministries) and command and control locations would also have been recipients depending on their operational needs and condition.