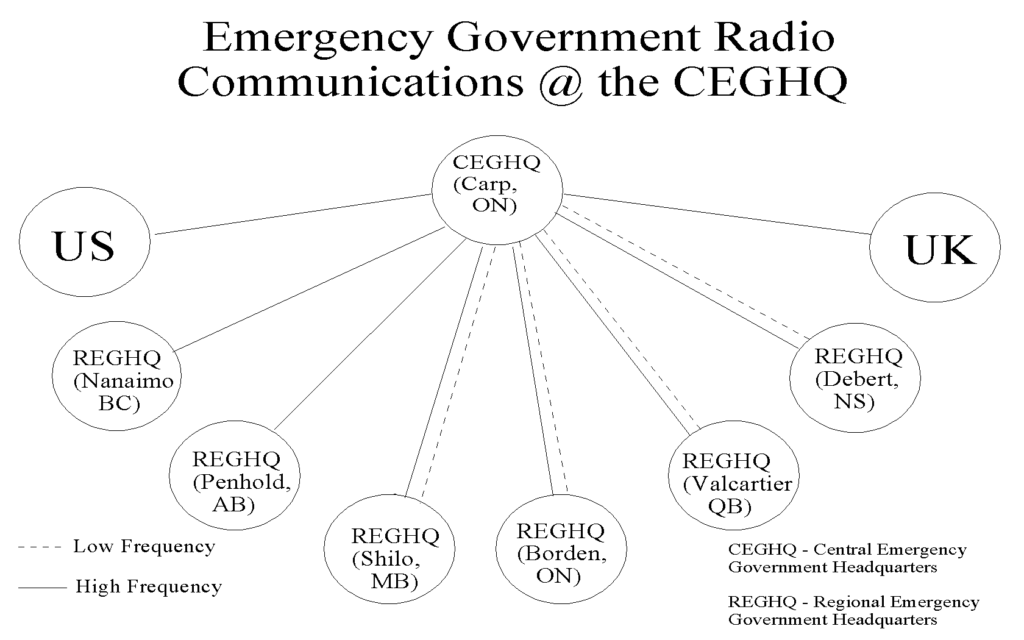

Click on the following link Hierarchy of Emergency Government Facilities across Canada. to see an organisation chart of the EGFs as of about the mid to late 1980s.

EMERGENCY GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS ACROSS CANADA

The CEGHQ (The Central Emergency Headquarters at CARP, ON)

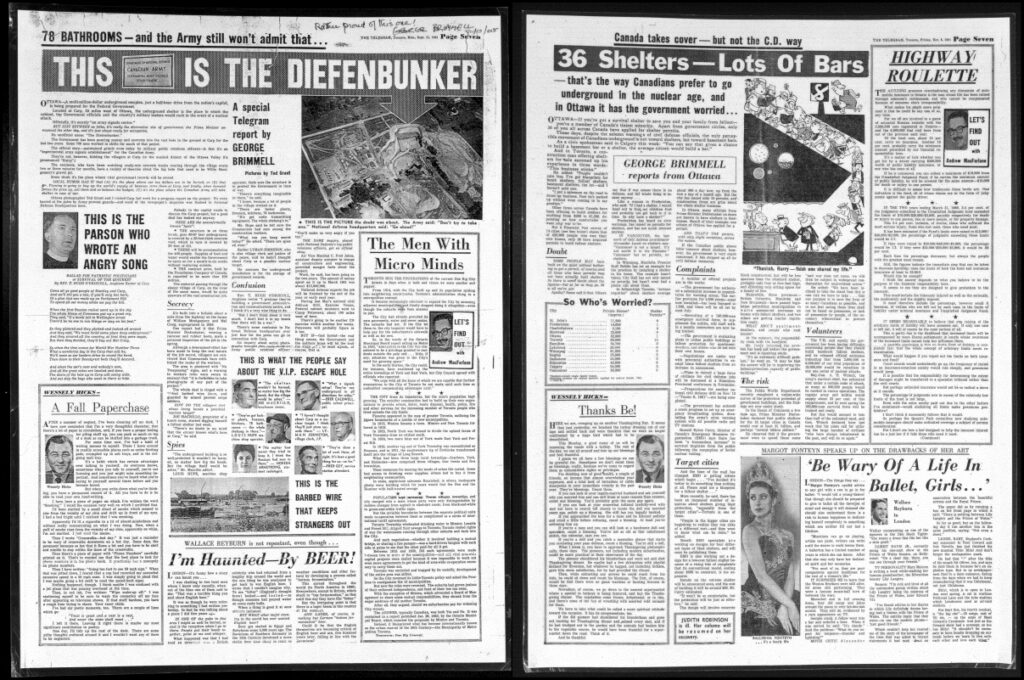

The flagship of Canada’s ‘system’ of Continuity of Government emergency government fallout and blast ‘bunkers’, the CEGHQ was built from1959 to 1961. It was ‘secretly’ constructed under the supervision of Department of National Defence Military Engineers and Signal Staffs by Foundation Company of Canada (Montreal) using then recently developed Critical Path Method of Project Management and appears to have been completed on-time and on-budget. The ‘Secret’ was not-so-secret as the above article by journalist George Brimmell demonstrates! At the time Prime Minister Diefenbaker was reportedly furious when this article appeared in the Toronto Telegram newspaper on Sept 11. 1961 before the bunker was even fully completed or operational.

It consists of four floors, a Bank of Canada Vault extension and an external “Garage” on about 80 acres. The main building totals just over 100,000 square feet of usable space. It cost approximately $20 million for structures (about $110 million in today’s dollars). It is a monolithic structure (about 154 ft x 154 ft square, 60 ft “tall” box) designed to resist a nuclear detonation by displacing a few inches in a five foot thick envelope of gravel. Its construction required some 5000 tons of reinforcing steel and about 33,000 tons of concrete. Top and bottom slabs are each about five feet thick. There are 36 columns each about 4.5 ft in diameter (and each capable of supporting 6900 tons) enabling the building to withstand a design overpressure of 100 psi (which would have put about 3500 tons force on each column).

In the ‘bunker’, the function of the Central Emergency Government was to prepare for the emergency and should it have occurred, the maintainance of continuity of control and direction of the country as much as possible while managing survival and recovery operations. Some of its primary operational activities include; overall national preparedness, warning, direction giving in relation to protective measures, management of national resources in accordance with defence commitments and regional needs, international affairs, post-attack analyses of the national situation and saliently, the survival of federal constitutional authority.

Much more on the Diefenbunker as the CEGHQ in the next section of this website.

Richardson Detachment

The CFS Carp Richardson Detachment was a military operated radio communications transmitter station linked by landline to CFS Carp located off Lanark Country Road 10 East of Perth, Ontario. The detachment was built with a hardened two story underground bunker built to accommodate the Signals personnel needed to operate the transmitter in case of war, but did have a mess hall, sleeping quarters, offices, decontamination facilities, and its own power generation facilities. Its location was chosen to be far enough away from CFS Carp to ensure survivability in the case of a nuclear strike against CFS Carp, and to reduce the risk of interference from its twenty powerful radio transmitters. The two-story communications bunker was constructed near Perth to the same nuclear bomb protection levels as the main bunker in Carp. There were no government officials to be located there. It was staffed exclusively by members of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals (RCCS), later 701 Communications Squadron post-Unification.

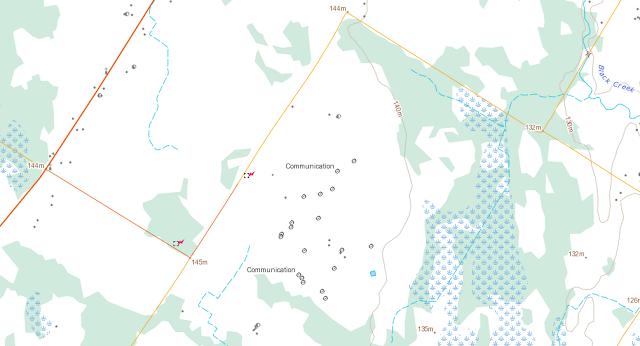

Separate radio receiver detachments were located and administered by CFS Carp in the region; the CFS Carp Almonte Detachment and the CFS Carp, Dunrobin Detachment were linked to CFS Carp by land line also.

In its first Canadian Forces Organization Order 1.16, dated 27 May 1968, the Experimental Army Signal Establishment was re designated as Canadian Forces Station Carp. On 14 September 1970 the stations consisted of a receiver site at Carp and a transmitter site at Richardson, Ontario, reporting to Canadian Forces Communication Command. CFS Carp was to provide the administration, security and housekeeping services needed to maintain a constant state of operational readiness for all sites under its command; most importantly, the communication facilities at Carp, Richardson, Almonte and Dunrobin. It also administered support services to terminal stations at Renfrew, Arnprior, Carleton Place, Smith Falls and Kemptville.

On 1 July 1971 CFS Carp was disbanded and reformed by amalgamating 701 Communication Squadron (formed on 1 April 1965) whereby it was given an increased operational emphasis on providing strategic communications for the Canadian Forces. The NATO Satellite Ground Terminal and some elements of the Canadian Emergency Measures Organization at Carp were ‘lodger’ organisations at CFS Carp, The Station was closed in 1994. Although the bunker was never used for its intended purpose, it did serve a valuable function as a government communications station staffed by RCCS personnel No. 1 Army Signals Troop.

Following the end of the Cold War, most of the emergency government headquarters were decommissioned, including CFS Carp and the Richardson Detachment in 1994. Those TeleCommunicaitons functions were taken over by CFS Leitrim outside of Ottawa.

A paper discussing the site location origins of the Richardson bunker transmitter site has recently been forwarded to me by one of the bunker’s volunteers. The paper, written by MCpl L.A. Palmer, seems to confirm that construction of the transmitter site was initially begun in the Cedar Hill area (see Mystery Square Lake article), but engineers ran into quality of rock and/or flooding problems causing them to abandon that site and relocate to the Richardson location.

NEW – This CEGHQ (Richardson Site) is for sale. Check out this recent article by Journalist Andrew King. https://ottawarewind.com/2023/01/31/bunker-debunked-a-secret-government-facility-revealed/

The CRUs (Central Relocation Units)

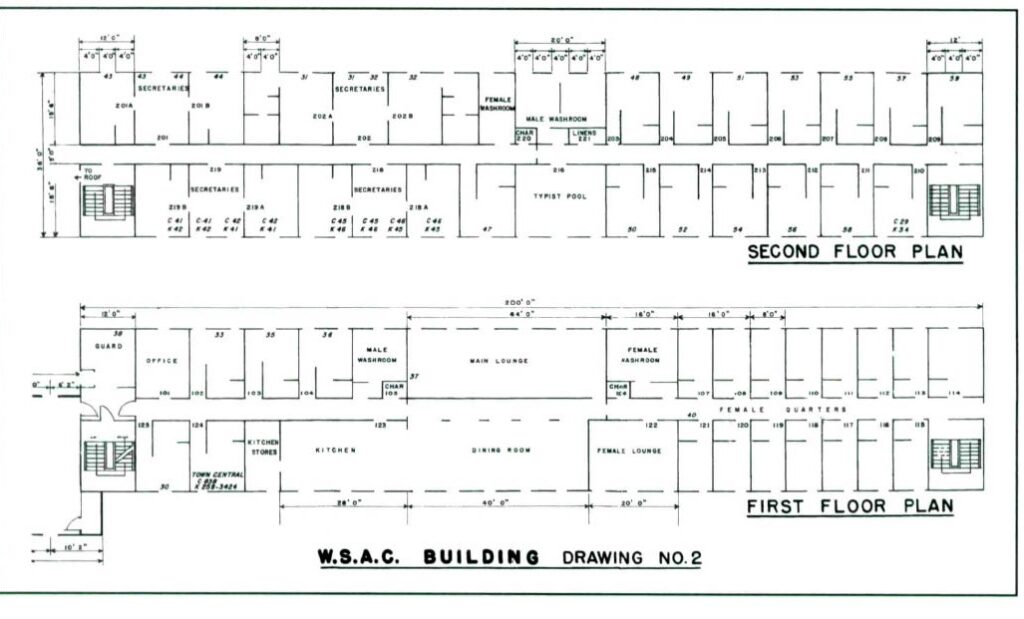

The Central Relocation Units were equipped with the basic materiel supplies needed to perform their support-of-the-CEGHQ role. Their fallout protected locations (and decontamination capable entrances) had basic operational capabilities, rudimentary sleeping and food preparation facilities, water, rations and operations supplies. Diesel electrical power generators and fuel tanks would have permitted them to remain functional for at least two weeks. They were supported by VHF radio and telephone equipment to ensure they remained in constant contact with the CEGHQ. CRUs were a functional extension of the CEGHQ and were located in separate, lightly protected facilities some distance away from it. Departmental groups assigned to the CRUs operated independently of each other, taking their direction from senior departmental officials working in the CEGHQ. Their tasks were to provide technical advice and operational support to the CEGHQ, to undertake tasks specified by policy analysts, and to carry out departmental action to put into effect decisions and directions emanating from the CEGHQ. At least one of the CRUs would have had an additional role as the site for a duplicate Governor-in-Council and the requisite senior support staff. It may have had to back up the CEGHQ should that facility have been severely damaged or lost contact with its various subordinate headquarters. There were six CRUs in the Ottawa area. They were within VHF radio contact range of the CEGHQ and physically located within very lightly fallout protected federally owned facilities. Two of them were in custom designed buildings (Carleton Place and Kemptville). These facilities were mentioned in a memo by the then Clerk of the Privy Council R.B. Bryce as covert locations to train public servants for potential duties in the CEGHQ. See the memo HERE!

The REGHQs (Regional Emergency Government Headquarters)

In a nuclear attack on North America both communications and transportation links from the national down to the local level were likely to have been severed or at least severely disrupted. For this reason the continuity of government plan envisaged the provinces becoming “regions.” As a region, a province would have been administered by an emergency government which has the federal /provincial authority to operate independently should it become isolated due to physical or communications disruption. Regional emergency government would then have become a significant link in the chain of continuity of government. Regional boundaries were coincident with provincial boundaries. Despite the inclusion in regional government of specific federal elements located in the provinces and territories, the major component of government would have been that of the province concerned. Thus provincial considerations were of major importance in establishing each Regional Emergency Governmnet Headquarters (REGHQ). The primary purpose of REGHQs was to provide fallout protected, self supporting facilities outside potential target areas and away from the seats of government, and to plan to relocate essential staff to them during the readiness phase

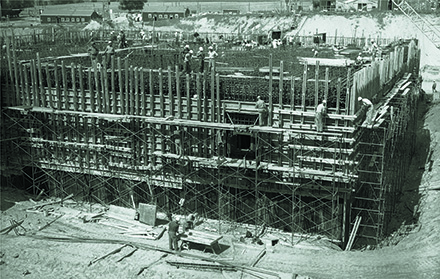

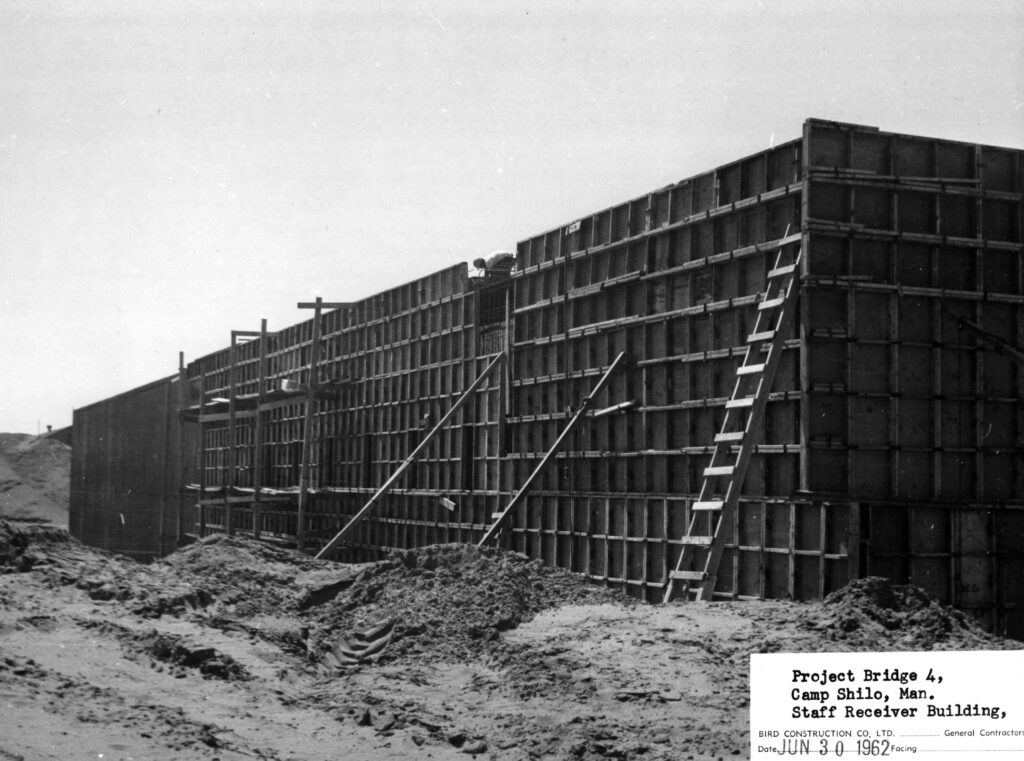

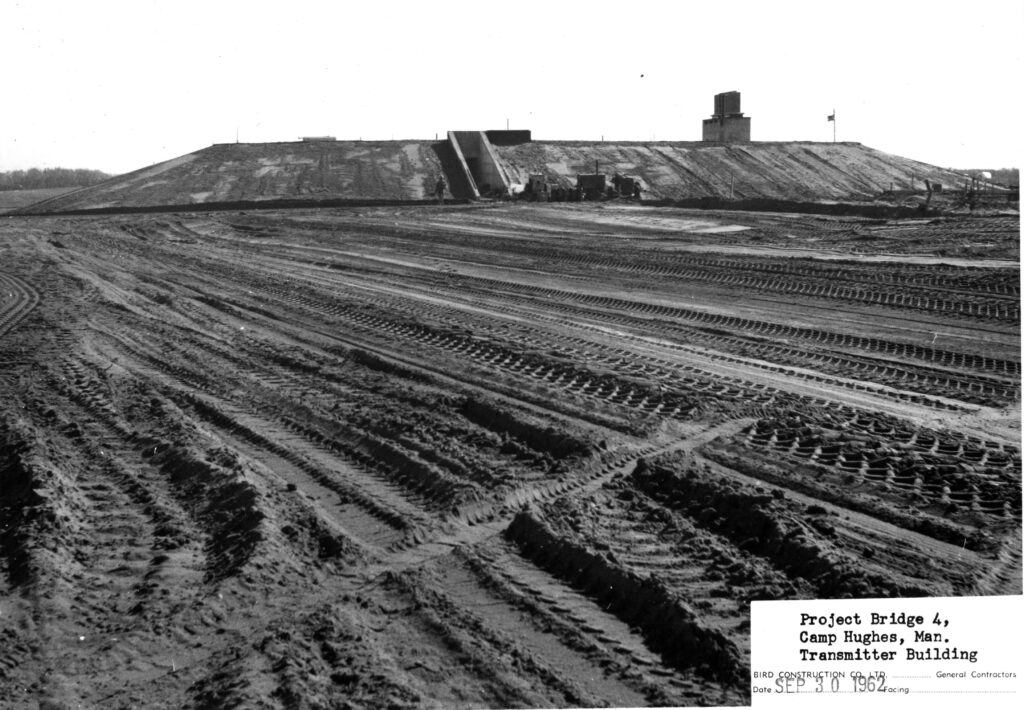

Three Construction Photos of the REGHQ Site at CFB Shilo, Manitoba (Early 1960s)

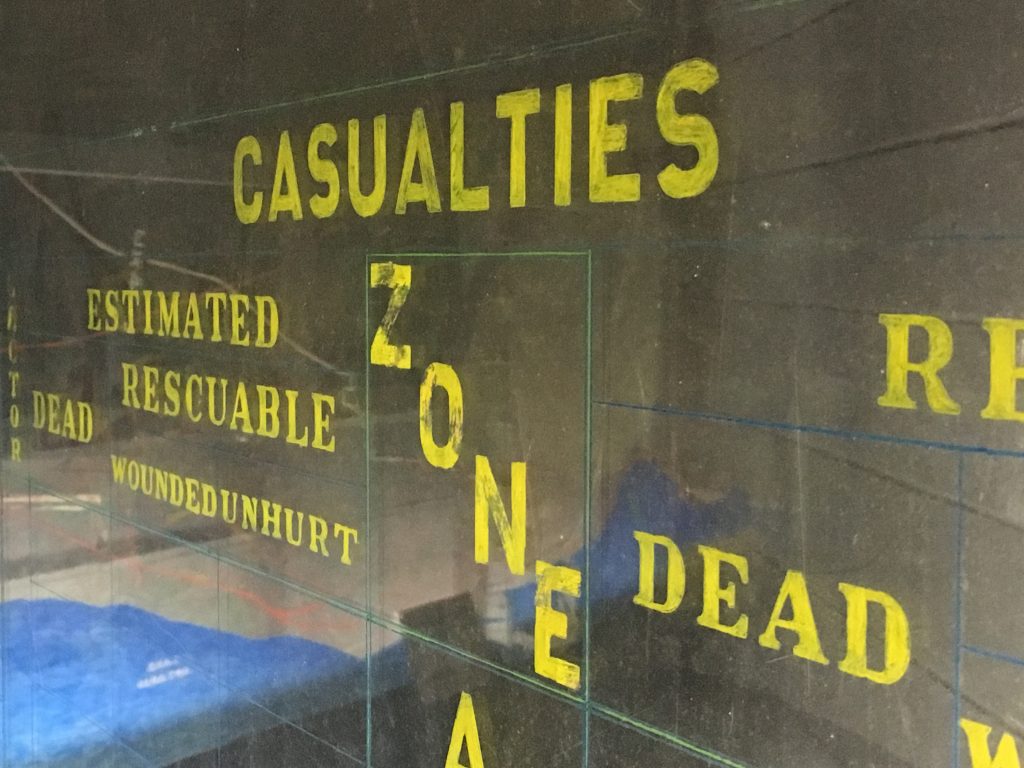

An REGHQ was comprised of regional (provincial) government, including elements of the provincial and federal governments, which would have formulated policy and directed essential operations during the survival phase, a Canadian Forces element which would have controlled all military resources assigned to assist the civil authorities in the region and provided the REGHQ with nuclear attack data,. a DND-operated military communications facility which would have provide regular and emergency communications. The organization of an REGHQ included the Executive Group (the Lieutenant Governor-in-Council comprised of the Lieutenant-Governor and a minimum of four Ministers one of whom probably would have been the Premier) and the Executive Support Group consisting of an Operations Directorate (public protection services/functions such as fire brigades, police, urban search and rescue, etc.), representatives of resource agencies, construction and maintenance engineers, food and supply experts, medical resources officers, etc., various advisers and Canadian Forces elements.

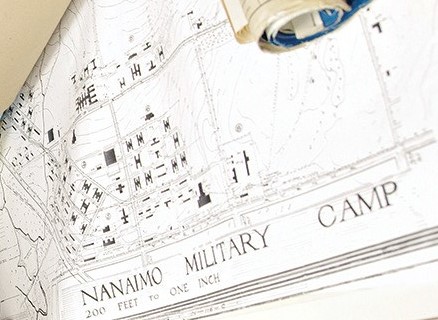

NANAIMO REGIONAL EMERGENCY GOVERNMENT HQ (Construction Photos)

These photos are taken from a collection of several hundred produced for the DND during the construction of the Regional Emergency Government Headquarters, otherwise known as the ‘Staff/Receiver Building, Operation Bridge’ in Nanaimo, British Columbia. The complete collection is presently held in the archives of the Central Emergency Government Headquarters (The Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum) in Carp Ontario. The collection was curated March 7, 2004 by Doug Beaton (a retired Parks Canada conservation expert), who for two decades volunteered as the Museum’s Collections Manager and was largely responsible for the creation, growth, documentation and maintenance of its Archives, Artifacts and Library Collections.

Clockwise Index

#1 View looking northeast prior to construction Sept. 5, 1961

#2View looking southwest during excavation October 2, 1961

#3 View looking south southeast during pad construction November 6, 1961

#4 View looking south during wall construction November 20, 1961

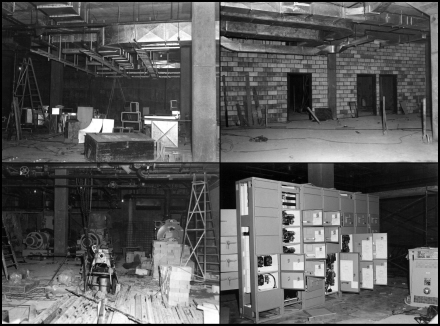

Clockwise Index

#5 View looking east during construction of 100 level December 4, 1961

#6 View looking east during construction of 100 level December 18, 1961

#7 View looking north during construction of 200 level January 29, 1962

#8 Aerial view looking west February 19, 1962

Clockwise Index

#9 Interior view on level 100 March 12, 1962

#10 Interior view on level 200 May 7, 1962

#11 Interior view towards generators May 28, 1962

#12 Interior view of power panel, Room 1001, June 25, 1962

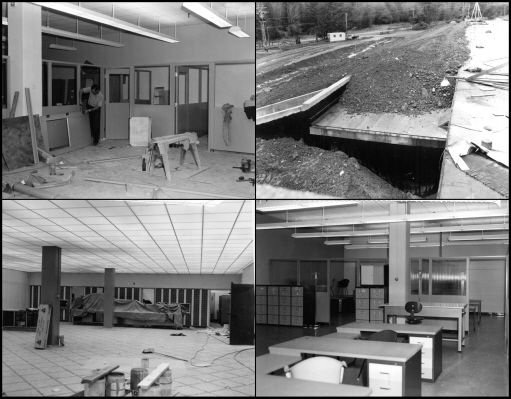

Clockwise Index

#13 Interior view, installation of office areas September 24, 1962

#14 Exterior view, covering of front entrance November 5, 1962

#15 Interior view, outfitting cafeteria December 17, 1962

#16 Interior view, installation of office furniture, February 25, 1963

Six provinces (BC, AB, MB, ON, QB, NS) had ‘proper’ custom designed and constructed facilities located on military bases remote from their capitals. Construction of the remainder was stopped when the Trudeau (the 1st) government came into power in the 1960s and only so-called interim non-protected facilities were put in place for the remaining four provinces (SK, NB, PEI, NL).

REGHQ Valcartier, QB Diefenbunker Volunteers Tour March 2002

Photos taken by Doug Beaton during tour of the facility post its Y2K significant modifications. Also touring were Bob Borden, Dave Peters and Paul Lauson).

REGHQ Debert, Nova Scotia…The following is an article about CFS Debert, NS from a telecoms point-of-view. This is from Station Warrant Officer R.J. Whitaker’s Website which unfortunately is no longer active.

CFS Debert – The End of an Era

“CFS Debert is a DISO unit under 72 Communications Group, Halifax. Its primary role was the operation and maintenance of an Automated Defence Data Network (ADDN) Communications Node. It is also the hostStation to three lodger units: the Central Medical Equipment Depot (CMED), the NATO Integrated Communications System (NICS), and the Regional Emergency Government Headquarters (REGHQ) until its closure in 1994.

The Station of Debert and in particular the Communications Branch was restructured in July of 1995 under the direction of DISO with an impending “closure” of the Station during APS 96. To date, there still is no order for the closure of CFS Debert, but rather an ongoing major restructuring and downsizing of personnel due to the closure of the ADDN node.

Communications and Electronics Branch personnel were the backbone operation of CFS Debert and employed approximately 82 Rad Ops, Tel Ops and technicians in support of the ADDN node. The ADDN was the mainstay of the Strategic Message Switching System(SMSS) and provided round-the-clock secure data communications for DND. The ADDN was comprised of three Nodes located at Debert, Penhold and Borden. User terminals (COMCENS) accessed the system via concentrators which were connected to one of the three Nodes. Also connected to the Debert Node was the Maritime Semi-Automated Exchange (MSAX) Node from Mill Cove. TheNICS system and the American AUTODIN were linked via the Debert concentrator.

CFS Debert Node, housed in an underground bunker, a “Dieffenbunker”, also provided operations staff as required to ZoneEmergency Government Headquarters (ZEGHQ) in Truro, Sidney and Kentville through user end terminals, until it was closed. The ADDN at Debert had remote capabilities via radio, accomplished with the use of a High Frequency Gateway facility. The ADDN was accessed normally byLong Range Communications Terminals (LRCT), by deployed Intermediate Range Communications Terminals (IMRCTs) and by Mobile Radio Teletype Detachments (CRTTZ).

As the implementation of the Newsdealer system became a reality, the ADDN Nodes became antiquated and manpower intensive for operations in today’s military, due to off-the-shelf systems which are much more cost effective. Cost effectiveness for today’s military forced the restructuring of communications systems, operations and manpower at Debert, but also throughout DISO, other commands and organizations.

With restructuring, personnel at CFS Debert, normally employed within the Node or its connected facilities were posted to new locations and the equipment declared surplus. The buildings which used to house a multitude of military personnel are now void of people. The normal hub-bub of noise and movement of people throughout the hallways and byways of the SR Bunker ceased almost immediately as APS 95 struck. The technicians, mostly Rad Tech 221, were left to clean up twenty some odd years of equipment gathering, maintenance projects, paperwork, outdated publications and general system equipment.

At Debert, the few remaining technicians worked long and hard to ensure the right equipment and materials were salvaged, documented, tagged and returned to the rightful LCMMs, while still organizing the major pieces of equipment for surplus action. In its heyday, Node Debert was home to a great many Tel Ops, some with more than one trip down home to work and enjoy the Nova Scotian “Downhomer” way of life.

The Rad Ops who managed and slaved in the Facility Control Centre now have a taste of the Nova Scotian country side for that “Downhomer” feeling. The Eastern Gateway, “The Gateway to the World”, was also under the restructuring plan to relocate from the SR Bunker on the Station itself, to the Great Village Transmitter Site. The move of the Gateway, with both operators and technicians working diligently together, was completed under budget and ahead of schedule, proving that the dedication, professionalism and team spirit of our soldiers is alive and well in Debert.

It’s hard to believe that another era in the lifespan of CFS Debert is coming to a close. Since its beginnings at the start of WW II, a mere 30 square miles of land, to its present day size of approximately one square kilometre with a 600 yard range, the presence of a military organization has been housed at Debert. The loss of the Station’s ADDN Node and its ancillary area maintenance responsibilities, proved to be the final turning point in the lifespan of this unit. For those who have served here, lived here and grew here; as our motto states, stay “SHARP AND SURE!” ….. Revised: 24 Oct 96″

EXTRACTS FROM THE DEBERT HISTORICAL SOCIETY WEB SITE

The Debert Military History Society (DMHS) began in November of 1997 when a small group of concerned citizens felt it was important to preserve the military history of the former Camp Debert (16X, RCAF/RAF) and to restore the former CFS Debert Museum which closed in 1995 when the military pulled out. Built in 1939-40, Debert was a staging area for an estimated 30,000 soldiers being shipped overseas to fight for our freedom in World War II. For many of them, Debert was the last Canadian Base they would ever see. Many stories and poems (some not too complimentary!) were written about Debert. DMHS was incorporated as a not-for-profit organization in March of 1998 and planning for a museum got underway almost immediately. On June 1st 1998, a lease was signed with the Colchester Park Development Society (CPDS) for the use of Bldg.213, a war-time “H-hut” and work is presently being carried out to have the museum open during the summer tourism months. The museum is quickly becoming a prominent tourist attraction and is advertised nationally in Legion Magazine and other tourist brochures. A summer student is usually hired as a guide for visitors to the museum and to help research and record war stories from veterans and local residents. Fund-raising is carried out by membership drives and various other activities. Visitors are often awed by the huge expanse of the military encampment and the stories about it.

In the early 1960s when Debert was selected for the Nova Scotia Regional Emergency Government Headquarters “Bridgesite”. (While the CEGHQ at Carp, Ont. was the E.A.S.E. site but irreverently called the ‘Diefenbunker’ after the Prime Minister at the time, the regional site were always referred to as bridgesites by the military). By the late 1960s the primary lodger unit at CFS Debert was 720 Communications Squadron. There were supporting radio transmitter and receiver stations built close by at Masstown and Great Village. (As was the case at all of the REGHQs, supporting telecommunications facilities were located ‘off site’ for protection purposes). Debert also had significant explosives storage magazines, various training facilities and a medical supplies deport which stores a number of emergency and N.E.S.S. ‘kits’.

What has become of the REGHQs today?

So what has happened at the six former REGHQ sites that were located on military bases across the nation? Click on the links below to see current Google views of these abandoned sites…

REGHQ Nanaimo, BC – Sealed in 1999, the Nanaimo Military Camp now occupies the land. Located just off the Fifth Street exit from highway 19. The Nanaimo REGHQ was one of the first such buildings to be sealed by the military after the EGFs program ceased to exist in the lates 1990s.

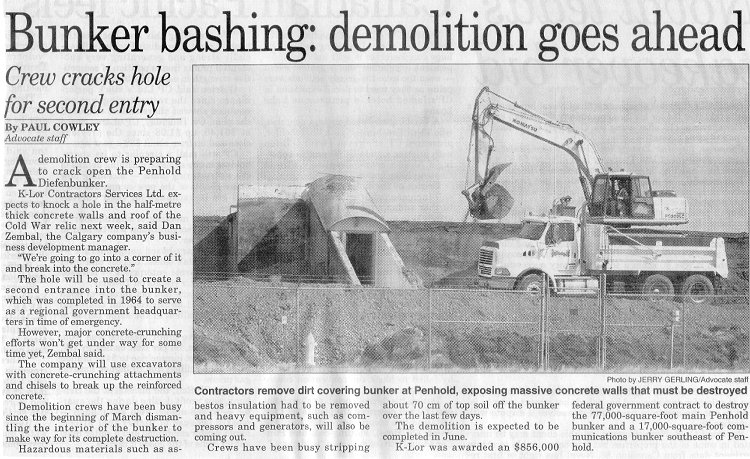

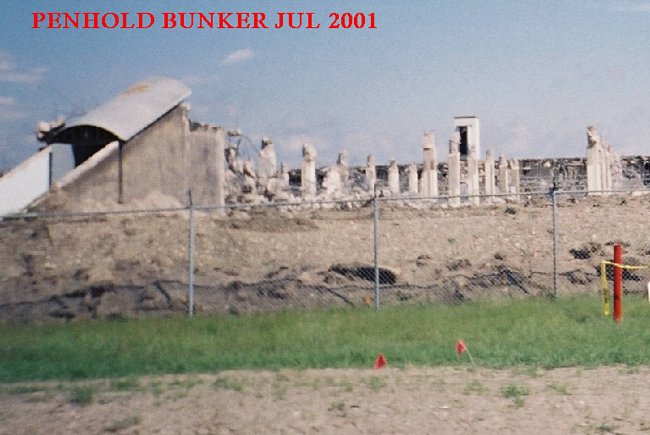

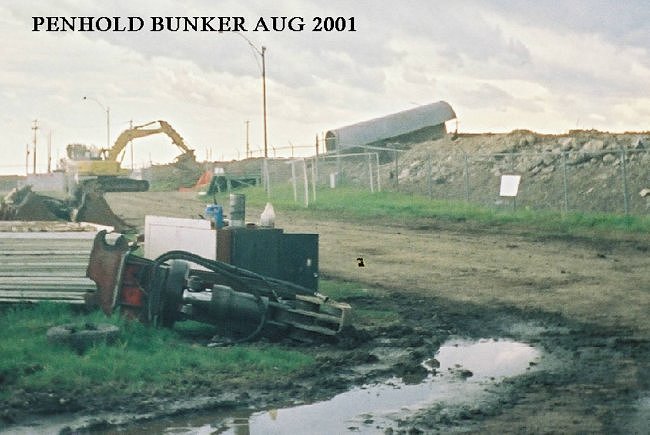

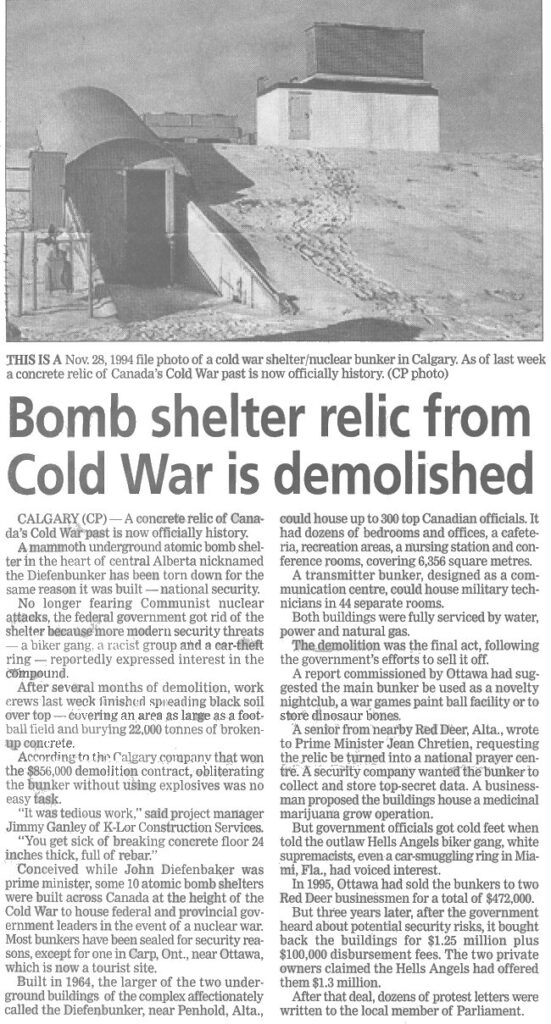

REGHQ Penhold, AB – In the late 1990s/early 2000s the facility was sold to a local (farmer?). Then it appeared that an ‘undesirable’ organisation wanted to purchase it. Rather than allow that the federal government bought it back (for many 1000s of $ more than they originally sold it) and then spend hundreds of thousands more $ destroying it! See the following article.

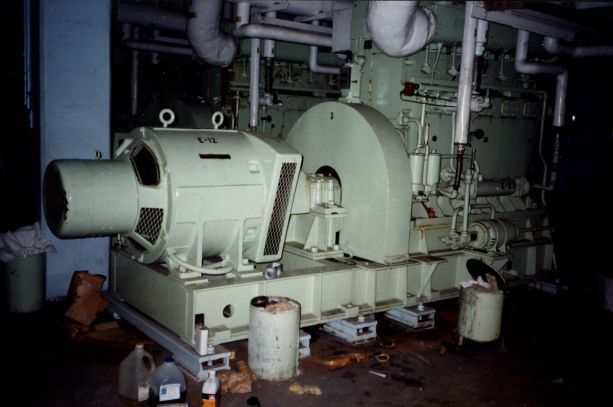

REGHQ Shilo, MB – Early in 2001 Dave Peters and Bob Borden visited CFB Shilo and were allowed to identify Furniture and Equipment that we wanted to preserve for use in the Diefenbunker Museum. The Base Staff fully cooperated in arranging to rescue and store these items until a year or so later when Laurysen Kitchens subsidized sending a tractor trailer to Shilo MB from Carp to fetch them. These items have contributed greatly to the reconstruction of various functional rooms in the Museum.

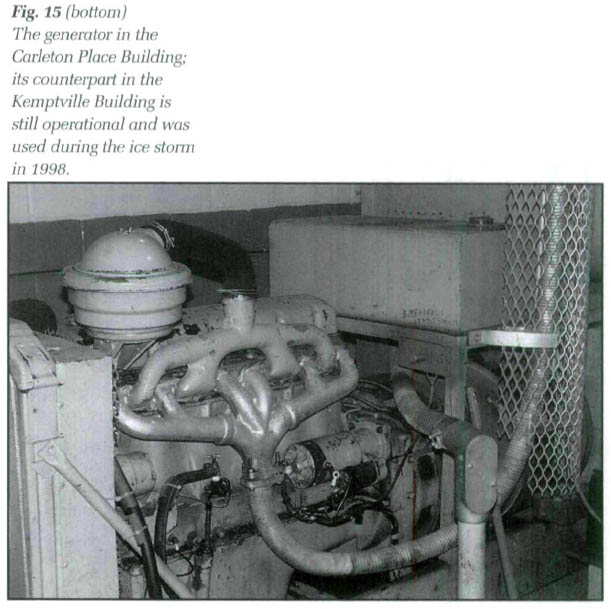

REGHQ Borden, ON – In the late 1990s a group of bunker volunteers visited the Borden bunker to attempt to acquire some of the F & E (and anything else that would help us “restore” the look of the Carp bunker). We only acquired a few items that trip but on later trips other volunteers were more successful, eventually acquiring a Mirlee generator (similar to the original generators in the Carp bunker) which was installed in the bunker 100 level machine room a few years later. Shortly after the last visit by our volunteers the Borden bunker was sealed.

One spring day in the early 2000s a ‘bunch’ of bunker volunteers drove to Valcartier, QB to have a look at the REGHQ there. Myself, Doug Beaton and Bob Borden were part of this group. Word was that the building was in quite good shape and was still being used as spare accommodation by the Base. When we got there we were fortunate to be taken on a tour by an officer of the Base (who seemed quite puzzled by our interest in the facility but never-the-less took us on a comprehensive tour). Unfortunately the building had been extensively modified in readiness for the Y2K emergency planning preparations, so that many areas of interest to us had been unrecognizably altered from their original configuation. Before we returned to Ottawa that afternoon (in a blinding snowstorm) we attempted to set up future cooperation with the individual in charge of the bunker but to no avail. We were trying to see if we could acquire some of the heavier kitchen equipment (which was virtually identical to that the military had stripped out of the Diefenbunker. We did observe that there were two CBC radio studio, one for english and one for french which was interesting.

From viewing the Google maps Satellite view the Base appears to be in the process of removing the earthen side and top cover from the building. Here is an interesting article in a recent (June 2010) from a website QuebecUrbain about the Valcartier bunker. (It includes a 1975 video with some inside shots – one of the telephones on the main conference room which would have been a provincial/regional-level equivalent to the Diefenbunker’s War Cabinet room).

REGHQ Debert, NS and Street View Front and Street View Side for profile views

CFS Debert was closed in the mid-1990s and decommissioned in 1998 with remaining military facilities being transferred to a local development authority named “Colchester Park”. The former regional bunker facility has gone through the hands of a variety of private owners and is currently an ‘historical entertainment destination’ in Nova Scotia. “From the historic to the radically fun, Enter the Bunker has something for the whole family”. They have tours, escape rooms, videos games, laser tag and they host birthday parties, team outings and corporate events.

No matter the season, no matter the mood, the Debert Diefenbunker has what you need to make a good day radically awesome!

The RRUs (Regional Relocation Units)

Regional Relocation Units (RRUs) had a similar role in relation to the REGHQ as the CRUs had to the CEGHQ. An RRU could also have been identified as an alternate REGHQ. The RRU’s main purpose was to have been a functional extension of the REGHQ, accommodating federal and provincial groups who could not have been housed in the REGHQ itself.

The ZEGHQs (Zone Emergency Government Headquarters)

The actual readiness of individual ZEGHQs varied considerably, both from province to province and within provinces, depending on the attitudes of their officials (and governments) towards civil defence. Most of the established ZEGHQs did have sufficient materiel on-site to fulfill their reporting and co-ordination responsibilities. As well having reasonable protection from radioactive fallout, most of them also had filtered air, equipped operations rooms, telecommunications (radio and/or telephone), sleeping and eating facilities, stores of rations and operational supplies, access to potable water and diesel generators and fuel for electrical power. The federal Department of Public Works was responsible for their fit up and on-going maintenance. Supply and Services Canada provided supplies including fresh military-style hard rations every two years. In an activation situation they would be staffed by local federal and provincial emergency preparedness officials. Depending on how seriously the particular officials took their responsibilities occasional exercises were run involving the activation of the ZEGHQs.

The MEGHQs (Municipal Emergency Government HQ)

(The following is a small bit of information about one of the few known MEGHQs – although recently a potential additional possibility has come to light in Kitchener, ON)

It was envisioned that provinces would encourage or insist that municipalities construct their own emergency fallout protected shelters to facilitate post attack survival/reentry operations in support of their populations. It appears that only a few municipalities did anything, however a few years ago one such facility was discovered in Aurora, ON. This underground shelter in Aurora, Ont (intended to oversee re-entry operations for the City of Toronto) is one of the few such municipal level bunkers known to exist. More on the Aurora facility HERE.

Beyond the Diefenbunker: Canada’s Forgotten Little Bunkers by Bill Manning (click on title above to see article)

This 12 page extensive article by Bill Manning first appeared in the Material History Review #57 spring 2003. A quote from Bill Manning’s paper: “Since the dismantling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, there has been a growing interest in the history of the Cold War. The work of authors Sean Maloney and Paul Ozorak, among others, has drawn attention to the Canadian government’s role in national and civil defence measures during this period. The “Diefenbunker” at Carp, west of Ottawa, now being restored and operated as a museum, serves as a fascinating reminder of the Canadian Government’s efforts to defend against nuclear attack. This complex, massive by Canadian standards, was never large enough to accommodate all the personnel and operations that would have been necessary during a national emergency.* Maloney and Ozarak allude to a network of other, smaller, facilities distributed throughout the Ottawa area. The “Diefenbunker Tours 1997” pamphlet refers to “some smaller bunkers” and to “a variety of relocation sites dotted throughout the country.” The purpose of this article is to explore the role of these smaller installations within the civil defence network in the Ottawa area and illuminate an important but neglected aspect of Canada’s Cold War preparations. ”

* Webmaster Note: The purpose of the EGFs in the CoG Program was NOT to fully or even partially provide an operationally functional government. It was to firstly provide for a thin thread of legitimate federal authority (as a means of staving off anarchy in the confused environment after a nuclear attack) as well a to provide a telecommunications equipped somewhat protected location where a relatively few knowledgeable public servants from each essential department would be able to collect, collate and analyze information and present it to the War Cabinet so that efforts could begin to plan for the aftermath. It would not have been possible to operate the federal government with the very limited resources available in the Carp or any of the other CoG facilities.

External Communications at The Central Emergency Government Headquarters/Canadian Forces Station Carp)

Background

1. The underground facility at Carp was ostensibly built as the Experimental Army Signals Establishment (EASE). The word ostensibly is used because while it was one of the most important Canadian military telecommunications sites for military message traffic during most of its existence it was also the primary site for the federal government’s emergency operations in the event of a nuclear attack on North America. Whatever the cover story it did make a good deal of sense to co-locate the government’s emergency operations capability with the military’s strategic telecommunication function because it would have been impossible for the government to be at all effective in the absence of good communications.

Redundancy

2. The facility had built-in a great deal of redundancy of telecommunications capability, not only with respect to the numbers and types of systems but also in terms of backups and alternate routes of transmission and reception of signals for each of these systems. This would have provided at least some capability to communicate with the outside despite the extensive damage that might have occurred to many of the systems.

Systems

3. EASE (later CFS Carp) had a considerable range of radio and telephonic links and systems available in support of emergency government operations. Long-wave (LF) and Short-wave (HF) radios would have provided links to a wide variety of outside agencies and to other emergency government headquarters including provincial governments in their regional shelters. The diagram on page 3 illustrates some of these connections. A Very High Frequency (VHF) network would have provided communication links to other federal government shelters in the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Valleys. Radio contact could be established with local air traffic if necessary.

4. A multitude of telephone connections (both by land line and in recent years by satellite) could also access the vast North American telephone network. (For concrete evidence of this note the masses of cut telephone cable pairs in the “Toll” room). From the facility telephone traffic would have been directed to a number of redundant break out stations into this network. The advantage of such a “mesh-like” network is that even though large portions of it would have been ripped out or destroyed in the attack, rerouting would have assured at least some degree of continuity of service to virtually anywhere on the continent. All commercial telephone companies were very cooperative in providing for this capability. Later in the facility’s existence a satellite ground terminal-SGF (the “golfball” at the base of the hill) provided more direct connections with NATO through the NATO Integrated Communications System – NICS).

Connects

5. As well as permitting voice and teletype communication within Canada to province and federal departments and agencies, these radio and telephone capabilities would have allowed contact with NATO Headquarters in Brussels, with other NATO nations, and with NORAD Headquarters in Colorado and North Bay, Ontario. Additionally the facility would have had communication with the US Special Facility (the US equivalent of the Diefenbunker) run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency at Mount Weather, Virginia. In preparation for an actual emergency (given a reasonable degree of strategic warning) many other organizations’ telecommunications systems would have been connected to the Carp Facility including the Canadian Police Information System (for the RCMP), the CN/CP Telex System, the Bell Canada TWX network and Atmospheric Environment Services’ Weather System to name a few.

Conclusion

6. Any kind of extensive nuclear attack would likely have caused very serious damage to both radio and telephone systems, especially in the short term. The inherent redundancies and flexibilities of these systems when combined with the large number of backup systems available would have permitted officials in the CEGHQ a reasonable ability to communicate within a few hours or at most a few days following an attack. However the speed of transmission (and thus the amount of information transmitted) would have been very limited for some time.