List of BLOGs (scroll down to see a particular blog)

BLOG # 15 – 02 Oct 2022 – The Replication (circa 2008-10) of the Federal Warning Centre (FWC) at the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum

BLOG # 14 – 07 May 2020 – A Bus Tour of Cold War Ottawa

BLOG # 13 – 04 May 2020 – Who Built the ‘Bunker(s)’

BLOG # 12 – 25 Apr 2020 – Security Guards at the Bunker

BLOG #11 – 01 Apr 2020 – EPC’s Emergency Radio (HF / Amateur Radio – ‘Ham’) Room – Background

BLOG #10 – 20 Mar 2020 – Nicknaming the “Diefenbunker”

BLOG # 9 – 19 Mar 2020 – Did the Cold War begin in Ottawa with the defection of Soviet Cypher Clerk Igor Gouzenko?And did it End with a Walk on Eugene Whalen’s Farm in Amherstburg, Ontario?

BLOG #8 – 15 Mar 2020 – ‘Diefenbunker’ Visit by PM Trudeau March 1976

BLOG #7 – 05 Mar 2020 – Article from the Cornwall Standard-Freeholder (a daily newspaper based in Cornwall, Ontario) entitled “Diefenbunker, Canadian Armed Forces, R.H.Saunders Generating Station, Cornwall, United States, Canada

BLOG # 6 – 04 Mar 2020 SOXMIS and “Moscow Molly”

BLOG # 5 – 02 Mar 2020 – The STRAD -Signal Transmit Receive And Distribution System and TARE – Telegraph Automatic Relay Equipment at the EASE – Experimental Army Signals Establishment ( the “Diefenbunker”) site at Carp, Ontario

BLOG # 4- 18 Feb 2020 -Continuity of Government versus Continuity of Constitutional Government (Consequences for the Central Emergency Government Headquarters – the ‘Diefenbunker’ in Carp, ON)

BLOG #3 – 14 Feb 2020 – Speech Given on the Occasion of the Official Dedication of the “Diefenbunker” as a National Historic Site – June 27th 1998

BLOG #2 – 22 Jan – Bed Spaces, Hot Bedding & Much More in the Central Emergency Government HQ (the ‘Diefenbunker’)

BLOG #1 – 20 Jan – The Bikini and the First Nuclear Bomb Tests

*******************************************************

Pls note that this BLOG is under construction.

BLOG # 15 – 02 Oct 2022 – The Replication (circa 2008-10) of the Federal Warning Centre (FWC) at the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum

The Federal Warning Centre (FWC) at the CEGHQ in CFS CARP (circa 1962-69)

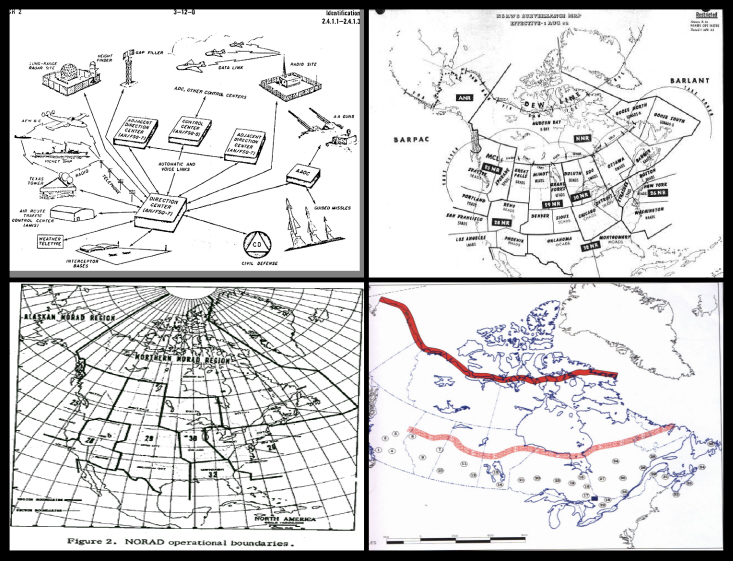

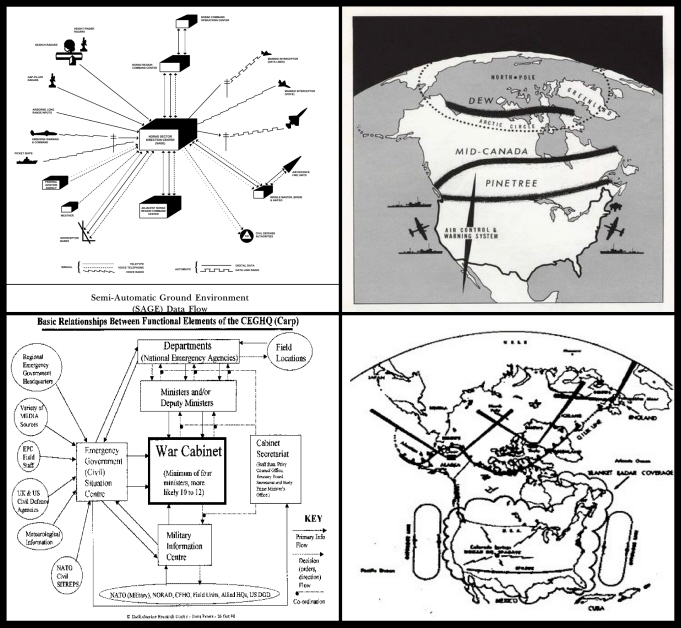

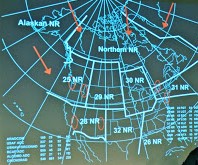

The purpose of the FWC was to receive, collate and analyze graphical and narrative information provided by NORAD (North American Air Defence) command and control facilities (the Colorado Springs HQ in the US and the North Bay HQ in Canada) concerning a large scale nuclear attack on North America and to make and promulgate decisions related to sounding of the attack warning system sirens, evacuation and stay-put instructions, the issuance of fallout warnings and the provision of input to commitment of civil and military National Survival Resources decisions.

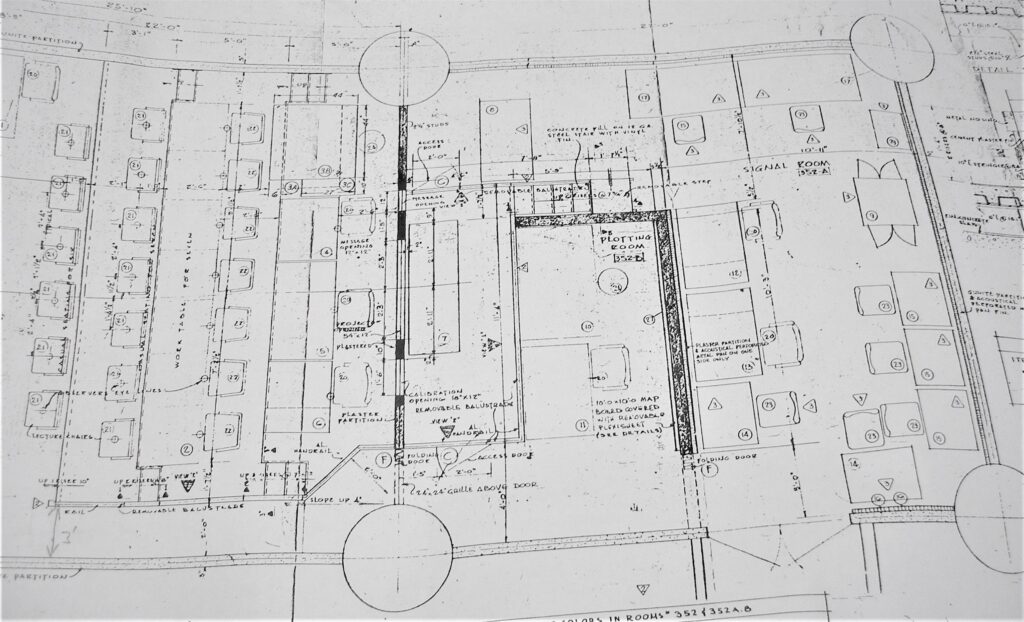

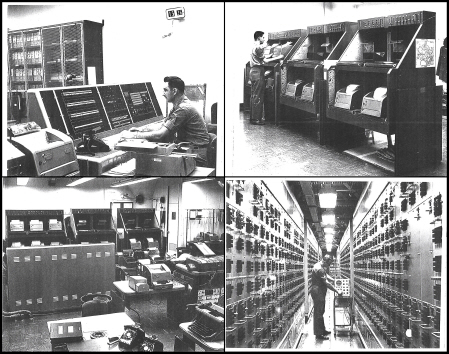

The Signals Room received the information either as telegram-type messages or in the form of punched tapes. The messages would have gone directly to the appropriate officials in the Display Room, while the punched tapes would have gone to the Plotting Room where they would have been transformed (by a special ‘etch-a-sketch’ type machine) into slides whereupon they would have been projected onto the Display Room screen for viewing by the Federal Warning Officer and supporting and officials and staff.

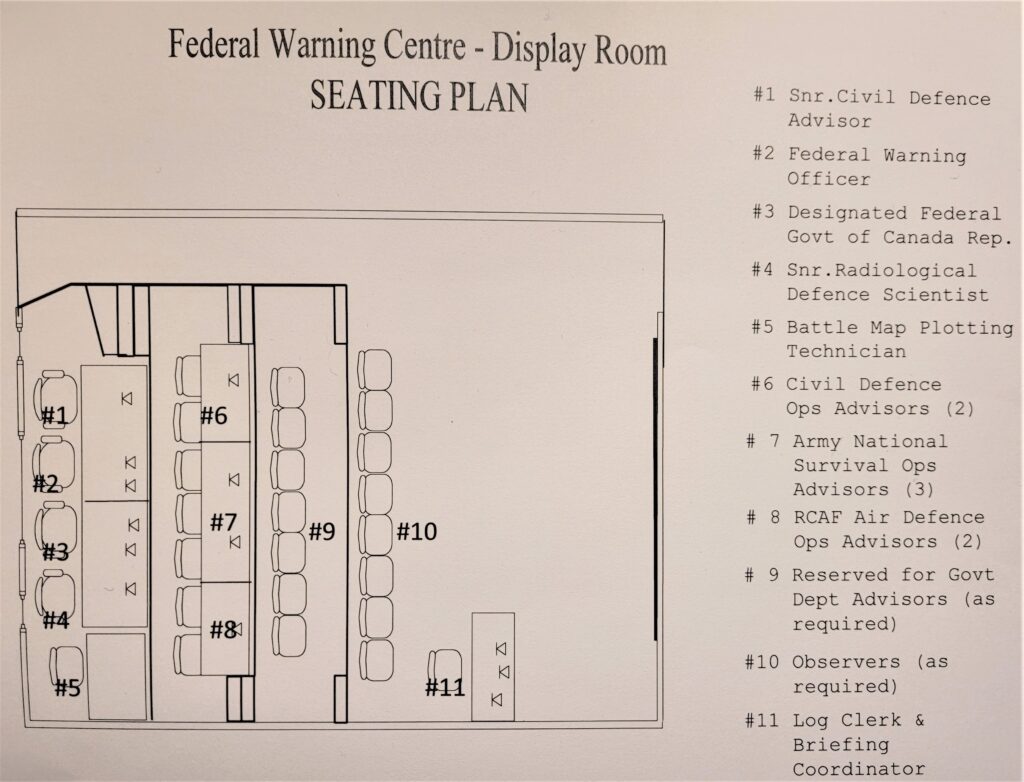

FWC Display Room

- On the top row of the theatre seating would have sat three or four fairly important individuals (the details of this are an informed deduction on my part-not much was formally written down of the subject of any standard operating officials that I have seen):

-The Federal Warning Officer (FWO), probably an Army Lieutenant Colonel (LCol). (During this period in the history of civil defence in Canada the government of Canada had given the responsibility for National Survival planning and operations to the Army because only they had the resources, command and control, and organisation to do the job). The FWO’s job would have been to decide when and where to sound the Attack Warning Sirens, when and where to order evacuations or issue stay-put instructions, when to activate the Emergency Broadcasting System, provision of initial information (such as NUDET and contamination areas) to Re-entry Columns, etc.

-The Head of Canada EMO (civil defence), a high ranking public servant (Director-General) whose job it would have been to advise and counsel the FWO on CD matters.

-A representative of Cabinet (Minister or designated Deputy Minister) to input to (and possibly override) decisions of the FWO. This person also would have kept Cabinet informed of evolving events and decisions.

-A VIP visitors ‘chair’ may also have been available on the top row for (for example the Chief Radiation Defence Officer, or a Senior Science Office ( or even maybe the PM or the GG!).

-Also adjacent to the top row (left) would have been a plotting table graphically recording the attack situation.

- The second row of the theatre seating was reserved for expert advisors, assessors and analysts.

- The third and forth rows were available for various observers, both military and civilian. It is likely that representatives from some of the federal departments and agencies along with officials from the Cabinet Secretariat and the Civil Defence Info Centre

There was a table located to the left of the bottom row which was probably intended for a recording (log) clerk

FWC Plotting Room

- The punched tape or message form information provided by the FWC Signals Room would have been used to produce Iconorama images for projection onto the FWC Display Room screen.

- The plotting room would have kept an on-going record (drafting table to the right of the top row of officials) of the plotted information as updates occurred.

FWC Signals Room

- This information would have been received by the teletypes in the FWC Signals Room (via either the Emergency Radios Room or land line possibly through STRAD, probably but not necessarily encrypted).

- Copies and/or originals of all punched tapes/message forms would have been kept in the Signals Room.

- The room would also have disseminated warning information status and decisions to various locations including (and most importantly) the REGHQs/the provinces, and to our US CoG/NORAD and NATO partners.

- It may also have passed on such info directly to certain designated offsite federal departments and agencies,

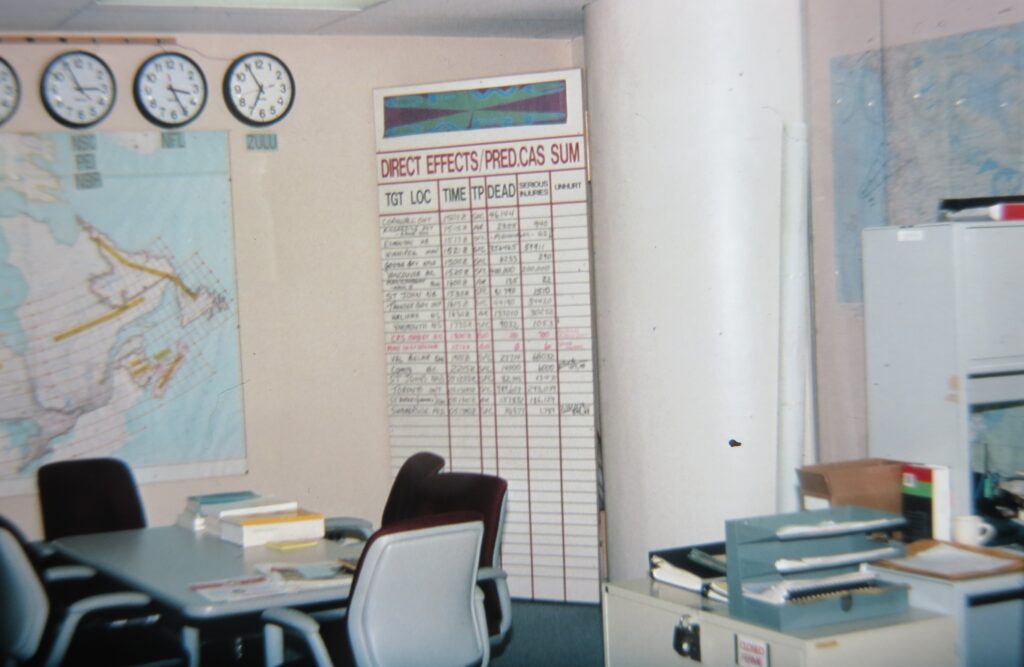

The Federal Warning Centre (FWC) in the Central Emergency Government HQ – CEGHQ – (at the Carp ON ‘Diefenbunker) was an integral part of the cross-Canada nuclear attack warning system from its inception after the bunker’s construction was completed in 1961 to when it began to be decommissioned circa 1991. It was the central location from which the alerts resulting from detection of an enemy attack would have been disseminated nationwide, activating the network of attack warning sirens and CBC-based emergency radio broadcasts. It also could have provided after-attack information on fallout movements and advice on shelter in-place and evacuation orders as well as all-clear and safe-move information. (This later would have also been a matter of close coordination with the Regional Emergency Government HQs (REGHQs) in most of the provinces).

It performed some of the most important functions of the ‘Diefenbunker’s’ raison d’etre, by providing the centre for coordinated nation-wide sounding of the attack and fallout warning systems . More specifically the responsibilities of the FWC , especially in the 1960 and early 70s are listed below:

- Monitoring military intelligence and Iconorama postings of incoming Soviet bomber fleets and responding NORAD interceptors (relayed from NORAD HQs in Colorado Springs / Cheyenne Mountain Complex and North Bay Ontario),

- Using this info in making decisions about triggering all or some of the nationwide network of about 1700 Attack Warning System sirens,

- Using this info to activate the CBC Emergency Broadcasting System (and to input info to the messages to be broadcast on the EBS),

- Using this info to inform federal and provincial Civil Defence Officials (most later called Emergency Measures Officials),

- Briefing the War Cabinet/ Ministers, Operations Officials (EmGoSitCen and Departmental and Agency Officials) on on-going air defence battle situation,

- Advising the War Cabinet on the implications of declaring various levels of Alert and implementation of various measures contained in the War Book.

Note: The FWC would NOT have had any significant input to the fighting of the Air Defence battle and the computer-based SAGE system.

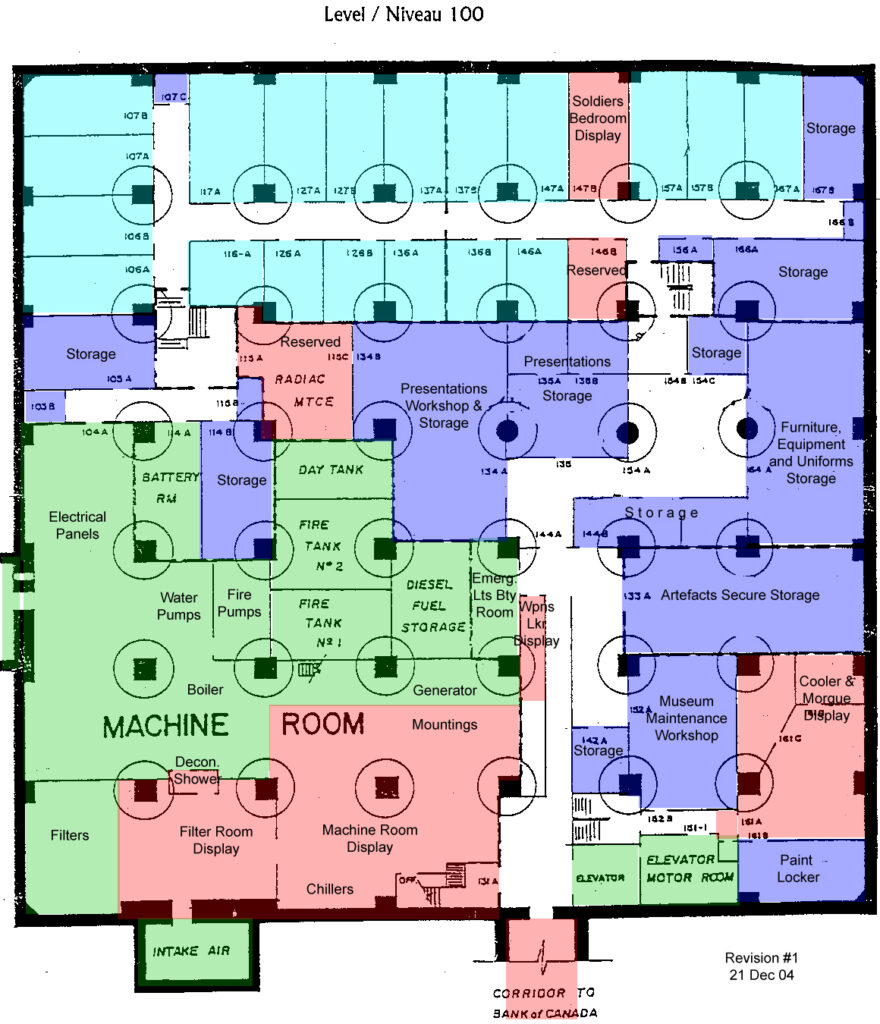

The FWC was originally located on the 300 level central to the War Cabinet room, the Emergency Government Situation Centre, the Cabinet Secretariat and various federal departmental offices (plus dedicated teletype and decoding rooms). Sometime between the late 1960s and the late 1970s the FWC was (rather inexplicably -its functionality would have been questionable in that location) relocated to the North Bay NORAD underground bunker). However in the early 80s it was moved back to its former location in the ‘bunker’ CEGHQ (see photo below).

Originally the FWC was a theatre-type ‘operations room’ with the North American air defence battle information projected from an iconorama to front-mounted display screen. The room was full of various staff officers and technical advisors feeding information and advice from a wide variety of external and internal sources to the Federal Warning Officer- (incharge of the whole operation). By the time the FWC was moved back to Carp the theatre seating and all the projection related equipment had been removed and the configuration was simply that of a large open office (see above).

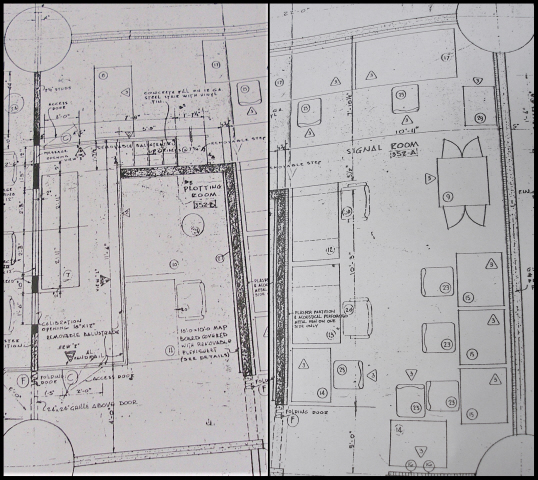

In its original layout (above) it consisted of three rooms, the main Operations theatre, to the rear of which was the Plotting (decoding and projection) room and beside it the (rather noisy) Signals (telecommunications) room. (It was noisy because of the large number of teletype terminals crammed into the small room!)

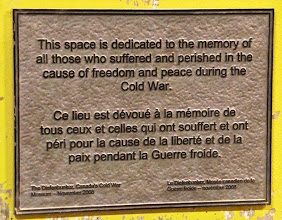

After the 1991 end of the Cold War and as the bunker was being transformed into Canada’s Cold War Museum, this open office area was initially used as space for an exhibit about the Strategic Threat to North America. When the original blueprints for the FWC area were ‘discovered’ (by volunteers Dave Peters and Dean McEwen in 2006) in the museum’s archives some years later it was decided to ‘reconstruct’ a slightly modified version of the original theatre style FWC.

This took a number of years for volunteers to complete the reconstruction and by about 2010 most of the work had been done. To finish ‘dressing’ the Operations Display Room a series of appropriate operationally pertinent wall charts (see below) and situation status boards were intended to be installed. Regretfully in the transition from a management to a governance Board of Directors and the hiring of professional museum staff seemed to have resulted in this ‘dressing’ project not being considered to be a high enough priority to finance. While this part of the dressing plan was never completed. Unfortunately the projection capability for this display was removed some years ago. Fortunately the then new Executive Director did find and acquire some of the flip-top school desks that were in the front two rows of the room, emulating what had been in the original FWC.

BLOG # 14 – 07 May 2020 – A Bus Tour of Cold War Ottawa

The City of Ottawa, Ontario was as involved in Cold War threat and response events as were Washington, London and Moscow. While the scale was smaller, some of the issues were very significant even seminal as the Gouzenko Affair illustrates.

Some years ago (2016?) I shepherded a tour bus full of my university alumni (UNB) on a “Cold War Tour” of Ottawa. After viewing four points of interest in the City area and viewing the bunker construction video, ‘The Nuclear Roof” (available for loan from the Ottawa Public Library) using the tour bus’s video system, we arrived at the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum. Then after a delicious locally-catered buffet lunch in the bunker’s Bank of Canada Vault deep in the lower regions of the Museum we had an extensive tour of the bunker including its restorations and reconstructions as well as its Cold War exhibits.

Believe it or not there are many Cold War interesting places to see in Ottawa, more than you would first guess.

A suggested tour itinerary and timing follow. Don’t forget to make arrangements with the Diefenbunker Museum well in advance, especially if you are a group and want to set up a catered lunch and have a tour guide accompany you.

0945 hrs: Tour group meets at the historic plaques in the park (Dundonald Park) opposite 511 Somerset St (Igor Gouzenko’s apartment). Short briefing. There is parking in the neighbourhood.

1000 hrs: Tour Bus parks on MacLaren St, tour group gets on bus and bus departs for Russian (former Soviet) Embassy on Charlotte St.

1010 hrs Slow drive by or stop in front of Russian Embassy, background briefing en route. Depart for CFS Leitrim. Brief on route.

1040 hrs Arrive CFS Leitrim bypass for slow drive by and en route briefing, Depart for Cartier Airport Alert hangers, on Alert Road.

1100 hrs Arrive at Alert Road, en route briefing and possible stop for photos at Alert Hangers, Depart for Diefenbunker. (Show “The Nuclear Roof” video en route – which you will have to borrow from the bunker ).

1200 hrs Arrive at Diefenbunker, Lunch (one hr), In-depth guided tour (1 to 1 1/2 hrs), response to questions, depart for start point in Ottawa at 1500hrs.

1600 hrs Arrive back at 511 Somerset street (end of tour).

The following are the various points of interest included on the above tour. Click on them for more details. The pieces are print ready for handout purposes.

#2. The Soviet (Russian) Embassy

#3. Canadian Forces Station Leitrim

#4. CFB Uplands Alert Hangers (and its Ordinance Magazines)

#5. Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum at Carp, ON (The CEGHQ at CFS Carp)

BLOG # 13 – 04 May 2020 – Who Built the ‘Bunker(s)’

What were the Primary Agencies Responsible for the 1959-61/62 Design and Construction of the Underground Nuclear-Bomb Resistant Experimental Army Signals Establishment (E.A.S.E.) Site, (the ‘Diefenbunker’ / Central Emergency Government HQ – CEGHQ) at Carp, Ont?

Background

Over sixty years ago on August 21, 1958 Prime Minister Diefenbaker announced in the House of Commons the establishment of what became the basis for the Continuity of Government Program (see Hansard of that date for more specifics).

“There is therefore a need, in our opinion, for the development of a decentralized federal system of emergency government with central, regional and some zonal elements. We intend to provide for a suitable central authority and to establish provincial, regional and zonal organizations through which a large amount of the work of the federal government could be carried on in time of war by the necessary delegation of authority to federal officers.”

Construction of the Carp facility (then designated by the deliberately misleading title Experimental Army Signals Establishment or Project EASE for security reasons) began in 1959. The Cold War was heating up at the time and there was a great deal of urgency to expedite completion of this project. Thus the usual somewhat ponderous government processes had to be sped up in order to ‘get on with it’.

There were three primary agencies involved in this massive defence construction effort. The Department of National Defence (DND) was the funding and requirements definition authority, On DND’s behalf Defence Construction (1951) Limited (DCL) was the contracting authority and the Foundation Company of Canada was the actual engineering design and construction contractor. Note that DCL (1951) has become DCC – Defence Construction Canada.

Overall Management

DND’s designated Project Manager was a no-nonsense Royal Canadian Engineer “Works” officer, Lt Col Ed Churchill -right- (who during WWII had constructed forward battlefield airfields up the length of Italy). He went on to be the Project Manager for EXPO 67 after completing the then very hush-hush EASE project. Lt Col Churchill appears having a discussion at a meeting shown in the film produced for Foundation Company about its construction, “The Nuclear Roof”.

Contracting

The Crown corporation DCL was selected as the contracting agency as it had already done well on a number of government / defence projects. It had been created in 1951 to help build massive defence infrastructure during the Cold War. DCL was notably involved in building the Distant Early Warning Line. It later became Defence Construction Canada (DCC) with essentially the same mandate. Its only client is the Department of National Defence.

The following is an extract from the history section https://www.dcc-cdc.gc.ca/english/history/of the Defence Construction Canada website where they list and describe some of the many projects that they have been responsible for contracting matters (including the bunker).:

“1961 – The Experimental Army Signals Establishment (EASE) – Commonly known as the Diefenbunker, EASE was built in Carp, Ontario between 1959 and 1961 to shelter Canada’s leaders in the event of nuclear war. It is designed to resist a 5-megaton nuclear weapon detonating 1.1 miles away, resulting in a 100,000-square-foot, four-storey structure surrounded by a layer of gravel five feet thick. Operated by DND from 1959 to 1994, the Diefenbunker is opened to the public as a museum in 1998.“

Construction

The Foundation Company of Canada was the primary design and construction agency which I believe later morphed into FENCO. Sometime in the late 60s or the 70s (?) the Company became part of Aecon, a large Canadian engineering design and construction firm.

For a 23 minute video made for the Foundation Company of the design and construction of the “Diefenbunker’ please click on this link – THE NUCLEAR ROOF *

*Sorry the above link to the Nuclear Roof video on the Diefenbunker Museum website is no longer working. One can borrow this video from the Ottawa Public Library, however I will shortly be attempting to download a copy to this website…stay tuned!

Just a few of the major achievements involved in completing this project on-time and on-budget included: (1) the integral use of the then new Critical Path Method of project organization and work control, (2) design to resist high levels of reversing above and underground shock-waves and (3) designing to shelter and provide work and living space for a large number of people in very confined conditions while totally physically isolated from outside support for up to 30 days and while ensuring their ability to communicate externally. The engineers involved met the challenges and more so. Almost 60 years has passed since the ‘bunker’ came on line and while well maintained for the first 30 of those, it has mostly ‘coasted’ as far as serious maintenance is concerned during its time as a developing museum. Amazingly enough most of it’s essential utilities systems continue to function reasonably well to this date.

On the history page (which -wow- goes back to 1867!) of its website Aecon notes some of the various projects that they (and their predecessor companies) have been involved in over the past decades. While I believe they used to proudly mention their Foundation Company of Canada role in constructing the 1959-61 (very advanced for its time) massive nuclear bomb resistant shelter, sadly they no longer do so. From the Internet Wayback Machine record of its 2012 website: “Aecon has a rich history that spans more than a century. In fact, Aecon’s history can be traced back to 1877, when Scottish immigrant Adam Clark started a plumbing and gas fitting business in Hamilton, Ontario. Since that time, Aecon has grown into one of Canada’s largest and most diverse construction and infrastructure development companies. Throughout the years, Aecon has been involved in the building of some of Canada’s most important landmarks, including the CN Tower, St. Lawrence Seaway, Highway 407 Express Toll Route, Vancouver Sky Train, and the Montreal-Trudeau International Airport, to name just a few. Aecon’s predecessor companies include some of Canada’s most renowned construction names. Over the years, companies such as The Foundation Company of Canada, Jackson Lewis, Lockerbie and Hole, Bannister Pipelines, Nicholls-Radtke, Pitts Engineering Construction, and Armbro Construction have come together to form what we now know as Aecon.”

Similarly with respect to Defence Construction Canada website they used to list and describe some of the many projects that they have been responsible for contracting matters (including the bunker). Unfortunately they also no longer do so. In 2012 DCC published a book entitled “ Breaking New Ground” https://www.dcc-cdc.gc.ca/documents/newsletter/Breaking_new_ground.pdf which had as its cover a photo of the EASE site under construction. On page 33 of that document was an article entitled “Going Underground” describing DCL’s role in construction of the ‘EASE bunker’ and the various BRIDGE Sites (regional bunkers) across the country. DCC maintains its’ corporate headquarters on Albert Street in Ottawa. This link and the subject document is no longer active or available. Pity!

BLOG # 12 – 25 Apr 2020 – Security Guards at the Bunker

A few days ago I was asked a question about security at the Bunker: “Would it have been chosen military personnel posted at the base who acted as guards? Or was there a contingent of MP’s manning and patrolling the guard house/escorting personnel within the Bunker?”

This is an interesting query and in line with my habit of over-answering such questions, the following is my response:

As I understand it a small MP detachment was assigned to the bunker. A duty MP monitored and operated the blast doors, signed people in, etc. That MP was armed with a 9mm pistol. He (or she) would have had a cot in the small alcove adjacent to decontamination centre. I believe there was a bar type high desk located at the open end of that alcove (the hallway side) where they could closely monitor the in and out traffic. I think they could also do fingerprinting ( but I’m not sure). They were also given the responsibility of controlling the flow of folks needing to use the decontamination centre.

At one time in the early 2000s we had reconstructed this space for display purposes with the desk and the bed and a mannequin dressed up as an MP but of course somebody didn’t like that and got rid of it. Too scary I guess! Later when the environmental support control systems were no longer monitored and controlled from the black platform (with the advent of the ‘Myrtle computer-based system about the mid 80s), the MPs based themselves on the black platform. You can see the wall mounted ammo storage canister built into the far wall.

For internal control purposes there would likely have been a small Base Defence Force just like most military bases had. These were usually a secondary duty. All soldiers have basic training and so have a basic knowledge of the use of small arms. That is what the weapons in the lockup near the battery room were for.

Finally there were rumours that in case stronger security was needed,(from an outside source – rioters, Spatnetz, zombies, etc.) a small detachment of soldiers could have been deployed from Petawawa. Since there were no dedicated accommodations for them inside the bunker, they would have had to be based in the blast tunnel (and presumably) been temporarily ‘invited’ inside during an actual attack).

If anybody has anything to add to this please contact me.

BLOG #11 – 01 Apr 2020 – EPC’s Emergency Radio (HF / Amateur Radio – ‘Ham’) Room – Background

In the mid-eighties we in Emergency Preparedness Canada (EPC), Dir Emergency Operations Coord decided that, in view of the move by the telephone companies (namely Bell) away from copper-wire based transmission line networks lines towards fibre-optic grouped mainline cables, which unfortunately made the “new” system more vulnerable to disruption, we needed to find a backup communication method.

Since we were in the process up a midlife update for the bunker’s civilian Continuity of Government Program, we just ‘commandeered’ the 400-level bedroom next to the facilities Emergency Transmitter Room. Its location, and the fact that it had one of the building’s emergency exits as an integral part of the room, (allowing running cable to the exterior of the building – and potentially to an antenna) a made it a good choice.

My Telecommunications Officer recommended building an HF Amateur Radio – ‘HAM” capability that would be able connect to each of our Regional Directors’ offices. We acquired sufficient HF equipment (over a couple of years) to create a crude but workable HF network. The original radio call sign for the Carp station was VE3GOC. The callsigns for the other EPC stations is unknown.

One of our main problems was finding enough Ham radio-qualified operators in each of Regional Directors’ Officer to support the operation of the network. By the late 1980s the network was operational, and I recall that we tested it regularly. It was voice only and qualified operators were in short supply but at least it gave us some degree of operational backup in the event of a serious problem with our primary means of communication, the telephone system. We partnered with Transport Canada to ensure we could access qualified operators in an emergency. My primary operations room was downtown Ottawa on the second floor of the Jackson Building at the corner of Bank and Slater (where we also had backup cross-country telecomms).

We in EPC were unable to convince DND to keep the Canadian Emergency Government HQ (CEGHQ) at CFS Carp open (or even to mothball it) and we had to move all our equipment out of the building in 1992. We moved it (including the HF radio equipment) to the Canadian Emergency Preparedness College (CEPC) in Arnprior and set it up there. In 1994 CFS Carp closed. I don’t know what happened to the HF equipment that was relocated to CEPC but we did get most of the CCTV and some other equipment back from there and set it up in the Diefenbunker as it was developing into Canada’s Cold War Museum.

When the Canadian Emergency Preparedness College was shut down, the original HF equipment was anonymously returned to CFS Carp, now the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum, where a group of devoted ‘Hams’ volunteers have recreated the room and its equipment which is still operational to this day, operating under the callsign of VE3CWM. Dave Peters and Brian Jeffrey

BLOG #10 – 20 Mar 2020 – Nicknaming the “Diefenbunker”

The “Diefenbunker” was an irreverent, but widely used nickname for the Canadian Forces Station (CFS) CARP, the location for the Central Emergency Government HQ (CEGHQ). There is no evidence that Prime Minister Diefenbaker ever visited the Carp ‘bunker’ (although he is sometimes quoted as saying he would never go there, preferring to stay with his wife Olive in the event of a nuclear attack!).

Who first coined the nickname “Diefenbunker” is not clear. It could even have been George Brunell the journalist who wrote an “expose’-type” article in the Toronto Star(?) 1961-62(?). Apparently that article so infuriated PM Diefenbaker that he personally tore a stripe off the newspaper’s editor for publishing it.

The other bunkers in the Emergency Government Facilities system had not yet been constructed. That process, including the construction of the Nanaimo, Penhold, Shilo, Borden, Valcartier and Debert Regional Emergency Government HQs (REGHQs), took place in the four or five years following the completion of the Carp bunker.

The correct reference by the military (at least initially) for the Carp Facility was the “E.A.S.E.” (Experimental Army Signals Establishment) site. This was a deliberate disinformation attempt. When the six other bunkers (regional/provincial) were constructed on military bases they were always referred to by the military as “BRIDGE” sites (possibly ‘bridging’ between from before a nuclear attack to after, or possibly as part of a disinformation scheme).

During my time with the Base Construction Engineers at CFB Uplands (or CFB Ottawa South as it became) when I first visited the Ottawa bunkers in the mid 70s, they were always officially referred as the Carp or the Richardson (Perth) bunkers. Later when I joined the Public Service with Emergency Preparedness Canada I found that the Carp bunker had been variously referred to as the Emergency Facility or the Emergency Government Facility (somewhat emulating the US who called their equivalent at Mount Weather, Viginia the “Special Facility” – which they still do as it is now FEMA’s main operational HQ).

All of that to say the casual usage by the Canadian military and public service of the term “Diefenbunker” always referred to the Carp facility. The other bunkers were always called Bridge sites or REGHQs, never Diefenbunkers.

BLOG #9 – 18 Mar 2020 –Did the Cold War begin in Ottawa with the defection of Soviet Cypher Clerk Igor Gouzenko? And did it End with a Walk on Eugene Whalen’s Farm in Amherstburg, Ontario?

BLOG #8 – 15 Mar 2020 – ‘Diefenbunker’ Visit by PM Trudeau March 1976

This photo, originally from the Canadian Forces Archives, was taken during a March 1976 brief helecopter visit to the CEGHQ at CFS Carp by Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Chief of Defence Staff LGen Jacquess Dextraze and Minister of National Defence Barney Danson. At that time the bunker and its real primary function as the emergency nuclear war location of essential federal government personages was ‘hush hush’. Not long after this visit PM Trudeau announced the existance of the facility and its’ purpose to the House of Commons. Thus the existance of the Central Emergency Government HQ became no longer a “SECRET”. It was rumoured at the time that the only comment that the PM made about the facility is that he didn’t like the paint colours in his suite.

Trudeau was the only PM to visit the facility….that we know of! There have been rumors that at one time during its’ construction Prime Minister Diefenbaker paid a surprise, incognito visit but to date no substantive evidence has been found to back this up. Given the character of the man, it is a dubious story.

BLOG #7 – 04 Mar 2020 Article from the Cornwall Standard-Freeholder is a daily newspaper based in Cornwall, Ontario. Diefenbunker , Canadian Armed Forces , R.H. Saunders Generating Station , Cornwall , United States , Canada (Todd Lihou – Published on September 13, 2012)

The days of the Cold War are long behind us – thank god. But when the United

States and the Soviet Union had their massive nuclear arsenals on a

hair-trigger, Cornwall would have likely been on the front lines when the

casualties were counted.

The reason? There was once a warhead in the Soviet stockpile of 30,000 weapons

that had Cornwall’s name on it.

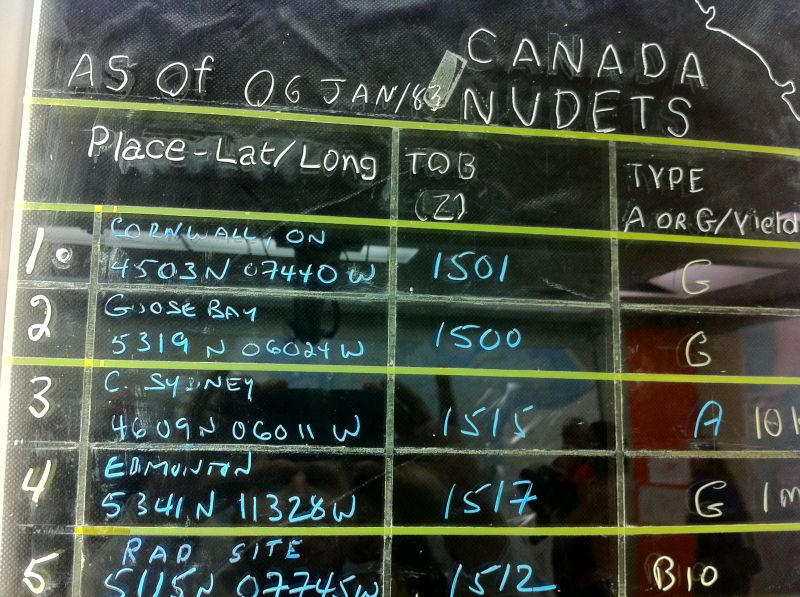

We know this because Canada’s Cold War museum, the Diefenbunker in Carp,

northwest of Ottawa, has maintained the last simulation (or wargame) to be run

at the facility. The simulation notes that on Jan. 6, 1983 at exactly 3:01 p.m.,

a nuclear weapon was exploded in the city as part of a massive, simulated,

attack against Canada.

Had the simulation been reality, Cornwall would have been wiped from the map –

one of the first, if not the first target the Russians chose, according to the

simulation.

Dave Peters, a retired colonel with the Canadian Armed Forces, who went on to

head up the nation’s civil defense readiness before retiring for good in the

late 1990s, now sits as a member of the Diefenbunker’s board of directors.

He said the weapon used in Cornwall would have targeted the dam at the R.H.

Saunders Generating Station, as well as the bridges that link us to the United

States.

The power of the weapon would have been so strong that people living in the

Riverdale neighbourhood wouldn’t have even known the bomb had exploded before

they were killed.

“You wouldn’t have even seen the flash,” he said. “We used to run those

exercises every December.

“We weren’t practising to see who would win. We wanted to make sure our

machinery (at the bunker) was working properly.”

The Diefenbunker was a hardened underground facility that was built to house the

upper echelons of the Canadian government in the event of nuclear war. It was

built in the 1959 as a four-level bomb shelter complete with broadcast

facilities for the CBC and enough food and water for more than 500 to survive

for weeks at a time.

It was decommissioned in 1994 and designated a national historic site. Now it

operates as a museum.

“NORAD would feed us targets” during simulations, said Peters, referring to the

North American Aerospace Defense Command, a joint military venture between the

U.S. and Canada. “It was our job to maintain communications and evaluate damage

and casualties.”

During the Cold War, or if strategic hostilities were to break out now between

Russia and the U.S., Cornwall could still find itself in the crosshairs.

“It’s an important target. There’s the dam and the Seaway locks,” said Peters.

“It would do economic damage to the U.S. and Canada.”

During the Cold War Cornwall was also the site of what were known as central

relocation units – essentially the basements of federally-owned buildings that

were converted into fallout shelters for other, less-important members of the

federal government.

Cornwall, and five other municipalities in eastern Ontario, held such

facilities. Ours was located in the basement of what is now the Cornwall Public

Library, but then Canada Post.

Peters, who was head of the nation’s civil defense preparedness at the time,

said while the idea of a fallout shelter in Cornwall looked nice on paper,

reality is another thing altogether.

Webmaster Note: I was not head of the Canada’s civil defence preparedness; I was the Director of Emergency Operations Coordination and as such was responsible for the civil readiness of the Federal Emergency Government Facilities (the bunkers) across the country.

“It was the worst of them all,” he said of the Cornwall shelter, adding there

were basement windows that were never covered up and would have made the shelter

useless in the event of an attack.

“They told me they would get some plywood and cover the windows and then cover

that with dirt,” said Peters, adding that would have never worked, had an attack

really occured. “Do you know how much time you have in that case?”

Today the Diefenbunker in Carp is one of the last such facilities in the

country. Every year several thousand people pass through its massive blast doors

to see what it would have been like for Canadian VIPs to ride out an attack

against the country.

It has even become moderately famous in Hollywood. Scenes for the Ben Affleck

blockbuster ‘The Sum of All Fears’ were filmed at the facility.

For more on the bunker, named after former Canadian Prime Minister John

Diefenbaker, check out diefenbunker.ca.

BLOG #6 – 04 Mar 2020

SOXMIS and “Moscow Molly” (RCAF’s 1 AirDiv History Website article “Spy vs Spy – Assorted Sources”)

SOXMIS. BRIXMIS, etc.

The Military Liaison Missions arose from reciprocal agreements formed immediately after the Second World War between the Western allied nations (U.S., UK and France) and the USSR. The missions were active from 1946 until 1990.

The agreements between the allied nations and the Soviet Union permitted the deployment of small numbers of military intelligence personnel — together with associated support staff — in each other’s territory in Germany, ostensibly for the purposes of monitoring and furthering better relationships between the Soviet and Western occupation forces. The British, French and American missions matched the size of the counterpart Soviet missions into West Germany (the nominal post-war British, French and American zones of occupations). The MLMs also played an intelligence-gathering role. The MLM teams were based in West Berlin but started their “tours” from the national mission houses in Potsdam in matte-olive-drab heavy cars. The Mission teams on a tour frequently comprised one officer accompanied by an NCO and a driver. The missions persisted throughout the Cold War period and ended in 1990 just prior to German Reunification. The missions were:

- British Commanders’-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany (BRIXMIS)

- La Mission Militaire Francaise de Liaison (FMLM) more properly MMFL in French)

- U.S. Military Liaison Mission (USMLM)

- and their reciprocal Soviet missions (SOXMIS/SMLM).

The British-Soviet missions were the first to be established (16 September 1946) under the terms of the Robertson-Malinin Agreement (the respective commanders-in-chief). It also had the largest contingent of personnel with 31 accredited team members. Later agreements with the US (Huebner-Malinin, March 1947) and France (April 1947) had significantly fewer permitted personnel, possibly because those Allied powers did not want large Soviet missions operating in their zones and vice versa.

“MOSCOW MOLLY” GIVES SECRETS OF U.S. AIR BASE – Airmen Taunted In Greenland, Former US Air Force Sergeant said here that “Moscow Molly,” a Soviet propaganda radio announcer, had taunted airmen at Thule air base in Greenland with detailed information that was supposed to he secret. Airman, Robert Guthrie (18), said the 800 men stationed at the 1top-of-the-world base were certain a spy was channelling information to the Russians. Guthrie said the propaganda siren would sometimes address an airman by name, give his hut number on the Arctic base and chat about the man’s wife and family at home. “Why don’t you go home; you could be wiped out!” Guthrie said “Molly” asked the men. He said the Soviet woman boasted that the Russians knew, what was being done at the base. Guthrie, a former tech1nical sergeant, said security officers were brought to the base and presumably investigated the broadcasts. But, he said, the men stationed at Thule never were given any hint of how Molly’s detailed information was leaking out. He said airmen believed she received the information by radio from one of the 8,500 civilian workers who built the base. However, he said he knew of no proof for that theory. Sometimes the Communist siren would inform the airmen of the arrival of planes and name the persons aboard them. “Sometimes she was 1right,” Guthrie said. (Trove…27 Sep 1952)

BLOG #5 – 02 Mar 2020

The STRAD – Signal Transmit Receive And Distribution System and TARE – Telegraph Automatic Relay Equipment at the EASE – Experimental Army Signals Establishment ( the “Diefenbunker”) site at Carp, Ontario

Introduction (by Dave Peters)

The STRAD was an integral component of the ‘bunker’ (EASE Site / CFS Carp / CEGHQ) from 1964 to mid 1981. It was located in the space on the 400 level along the ‘back’ wall, adjacent to the Message and Crypto Centres. As a member of the Base Construction Engineering staff I remember being taken on a tour of the STRAD in 1974 (or 1975) when it was operational. It seemed to be a very busy place. Of course it was NOT the raison d’etre for the bunker (as some observers may have falsely concluded); it was however intended to be the primary means by which elements of the Emergency Government communicated with each other and so the reason for its placement in the bunker. The master control console is on display in the main hall of the Military Communications Museum in Kingston. Ms Annette Gillis, Curator for the Museum kindly sent me these images of the STRAD console on displa

When the STRAD was replaced by the SAMSON system (1981 or so), the 300 level bedrooms and offices displaced by SAMSON in what became the Ottawa Semi Automatic Exchange (OSAX) were reconstructed in the 400 level area vacated by STRAD. During the period (mid 1960s to early 1980s) of the Federal and Provincial Governments’ relative neglect of Civil Defence including the Continuity of Government Program’s Emergency Government aspects, the existence and use of STRAD is probably the only reason why the Carp facility was not closed, as it was the main Canadian military communications system during that period. Most of what follows is a condensed and edited version of what is on the RC Sigs / Military Communications Museum’s ( Kingston, Ont) website. https://www.candemuseum.org/home

Background (co-ordinating author CWO Garry Dowd (Ret’d), edited by Dave Peters)

In September 1959 under Civil Defence Order 1959, the Army was made responsible for providing warning to the public of attack and the radio-active fallout resulting from nuclear explosions and for the operation of Emergency Communications for the Government. On 31 May 1960, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker announced a plan to provide each Province with a centre from which a small core of Federal and Provincial staff and facilities supported and manned by Army personnel could direct emergency operations within the province, even in the presence of nuclear fall-out, the loss of communications and possibly the destruction of the federal capital and some provincial capitals. The army became responsible for emergency command, for attack warning, for the prediction of fall-out patterns and for a number of other important services. Planning proceeded for a network of survivable, underground and hardened shelters for the continuity of operations of the federal government and the governments of each of the provinces. Planners ensured that adequate communications capabilities with enough redundant landline telephones, cryptography machines, teleprinters, transmitters, and receivers were incorporated into the plans.

The (primary) Federal Emergency site chosen was at Carp, Ontario with Provincial sites at Borden, Shilo, Penhold, Nanaimo, Valcartier and Debert. State-of-the-art teletype and other associated communications equipment were installed in the Provincial Sites. At the Federal Site at Carp, the first computer operated message handling system called STRAD ( Signal Transmit Receive And Distribution) system was installed to control the flow of traffic through the network. The system provided a much improved service to the network users until it was retired to make way for a more modern system. The Experimental Army Signal Establishment or “EASE” became the cover name for this facility, perhaps because there was an experimental Signals facility located in nearby Shirley’s Bay, just west of Ottawa. The name for the Carp facility – the National Emergency Headquarters – was later changed to the Central Emergency Government Headquarters or “CEGHQ”. The main operating centre at Carp was called the Federal Warning Centre (FWC). It was headed by a LCol, with five Majors on rotating shifts, an Artillery Sgt as Weather and Map Plotter and five rotating shifts (Communication Operators) in the operating centre with a Sgt as the overall daytime Supervisor.

Message Switching Automation

In the late 1950s, the British military had developed an automated message switching capability called STRAD (Signal Transmit Receive And Distribution) system and TARE (Telegraph Automatic Relay Equipment) that was based on existing procedures and which in essence automated the Tape Relay Centre (TRC) function. Messages were received on STRAD, routed by TARE and transmitted by STRAD. STRAD’s core capability was a magnetic drum storage device that recorded and stored messages prior to their onward transmission.

STRAD – Inception

On 22 Jun 1964, the Canadian Army Signal System activated a STRAD / TARE system at EASE in Carp, Ontario. The footprint of the STRAD equipment occupied 204 square meters. Carp’s STRAD was implemented to handle 69 teletype circuits and could be expanded to handle up to 90 circuits, operating at speeds of 60, 66 or 100 words per minute. The STRAD system was easily processing 9,000 messages per day, well below its maximum capacity of up to 83,000 words per minute. STRAD / TARE also saved much of the manpower required to operate the Tape Relay Centre (TRC). This was the first automated message system in the Canadian Forces, where a two or three person shift could do the operating work previously done by an entire TRC shift of a Sgt (shift supervisor) and about five TRC operators – a significant manpower savings. Based on initial success, there were discussions on implementing this STRAD / TARE system at other TRCs.

STRAD – Operations

The Carp STRAD was a first generation computer designed for use with digital communications systems. STRAD at Carp was the first installation of two similar British systems. The British system was installed at Boddington, UK and a similar system was installed in Australia. In Carp, the STRAD System was used to terminate both HF and LF radio circuits and conventional land-line circuits to all the Provincial Warning and Reporting Sites across Canada. The installation of the STRAD at Carp and the installation of more modern teletype equipment at the Nanaimo, Penhold, Shilo, Borden, Valcartier and Debert Provincial sites revolutionized the narrative message handling for the Army and other services across the nation. Concurrent with many of these happenings came the unification of the Forces with the subsequent changes to the communication system. In addition, STRAD was connected to a sister system in Boddington, UK which provided an important portal for communications to Canadian Units deployed to NATO Europe and other countries since the early 1950s.

STRAD was versatile in that it was always available to accept the input of messages and would then forward them immediately or if the system became too congested, the STRAD controller could place incoming messages in overflow storage, then retrieved and forwarded later. From 1964 until decommissioned in 1981, the STRAD system proved a highly reliable and secure message system. Prior to STRAD, Canadian military communications consisted of Tape Relay Centres (TRC) and Message Centres (later known as Communication Centres). With the arrival of STRAD the whole concept of military communications changed. There were still Message Centres but the TRC was gone. No more chad tape to step on and tear. No more an abundance of tape reels to store.

STRAD – Technical

The STRAD / TARE (Signal Transmitting Receiving And Distribution) / (Telegraph Automatic Relay Equipment) system was a transistorized fixed-program automatic message handling system developed in England.. The common logic part of the system was a fully duplicated and cross wired to its identical twin. The messages received were stored on a magnetic drum. Additional storage capacity was on an overflow, magnetic tape system. On 4 January 1962 Carp went operational. All the teletype equipment was in place and the Primary TRC (pre STRAD equipment) on the 3rd floor and the Message Centre on the 4th floor were fully operational.

In the spring of 1962 STRAD equipment started to arrive from England however STRAD didn’t go fully operational until 1964. In October 1962 Carp had its first lockup. The Cuban Missile Crisis had the USA and its allies very concerned. (It made little difference to STRAD personnel except for not going home at night). The cabinets carrying the ‘books’ of electronic equipment were approx 3.5 feet square by 7.5 feet or so tall and weighed 1,000 to 1,500 lbs each. This equipment was unpacked in the tunnel and man handled onto a dolly and carefully taken into the site for installation. This was a very difficult and physical job. In total approx 80 cabinets were installed. (The location of these can be seen on the plastic construction model). As noted above, on 22 June 1964, the STRAD / TARE system went active.

STRAD – Closure

STRAD closure ceremonies were held on 2 July 1981 with a parade and a fly past by a T33 Shooting Star. After the parade, the STRAD equipment shut-down was carried out by with a number of highranking Comm Officers and STRAD Maintainers in attendance. STRAD / TARE closed 17 years and 61 million messages later, when the Strategic Automated Message Switching Operational Network (SAMSON) – a computerized network using modern computers – went active.

BLOG #4 – 18 Feb 2020

Continuity of Government versus Continuity of Constitutional Government (Consequences for the Central Emergency Government Headquarters – the ‘Diefenbunker’ in Carp, ON)

The Continuity of Government (CoG) Program was originally presented to Parliament by Prime Minister John D. Diefenbaker in 1958 and, as excerpts from the August 21, 1958 Parliamentary record (Hansard) show, his statement was unreservedly supported by the then Leader of the Opposition, Lester B. Pierson. That in itself demonstrates the importance that our parliamentary leaders at the time attached to this matter. Given the increasing and evolving nuclear thtreat posed by the Warsaw Pact particularly the Soviet Union, Canada along with most other NATO nations made similar enhanced GoG preparations. The primary purpose of the CoG program from its inception was to protect and support the essentials of Executive federal government in order to preserve a ‘thin thread’ of legitimate national government through the chaos of a nuclear attack on North America. In such a scenario all that was required to pass whatever ’emergency regulations’ that would have been needed to deal with the situation was the assent of four federal cabinet ministers and the signature of the Governor General (Governor-in-Council).

A primary responsibility of Emergency Preparedness Canada (the agency charged with actualizing the CoG) was to support the implementation and readiness of the program as it was set out originally by Parliament and elaborated upon in PCO’s Emergency Planning Orders.

Then in 1988 the new Emergencies Act came into being (to replace the somewhat infamously, heavyhanded War Measures Act) and, more pertinent to our CoG readiness activities, the Emergency Preparedness Act was passed. The latter had much more specific ‘instructions’ and had a very significant impact (one that probably had not been fully anticipated by the authors of the new legislation) on the Emergency Government Facilities aspects of the CoG. As a result of the fact that the ‘new’ act called for Continuity of Constitutional Government, we had to rethink the numbers aspects of our Central Emergency Government Headquarters protective accommodation arrangements. We consulted a government lawyer who was expert in constitutional law to try to determine what was the minimum we had to do to meet the requirements of the new legislation. The word ‘Constitutional’ meant that government by executive decree was out and that representatives from the legislative and judicial branches of government had to be included in our protected locations.

After much analysis it was concluded that we had to provide for a quorum of each of the House of Commons, the Senate, the Federal Court and the Supreme Court. A quorum of the House of Commons is 20 (including the Speaker), of the Senate is 15, of the Supreme and Federal Courts five each plus various minimum support staffs gave us a ‘doable’ number. As I recall it the total number of ‘new’ occupants that needed to be provided for was only about 55 or 60. We checked out the environmental systems in the bunker and found we were OK for the increased numbers of persons involved from that point of view. The main problem was sleeping spaces even with “hot bedding” being the norm for most occupants. That and to a lesser extent, the matter of finding suitable ‘office/working’ spaces). In room 457A (across from the EPC HF Emergency Radios Room) we experimented with converting the double bunks to triple bunks. We calculated that there were sufficient civilian double bunked rooms that if modified to triple bunks (similar to those already installed in the military sleeping quarters) we could accommodate the extra people involved. (Locker space would have been tight). We never got around to sorting out where the quorums of Parliament/Judicial bodies would have met (presumable they could have made use of the War Cabinet room and the 400 level conference room and a few other larger rooms such as the ‘lounge area’ in the senior officials sleeping area on the 200 level. Nor did the potentially thorny question of whether or not, or to what extent members of the opposition parties would have had to have been included.

The end of the Cold War and the shutting down of the then “new” Continuity of Constitutional Government Program in the early 90s followed eventually by the closing of the Emergency Government Facilities by 1994 put an end to this planning process. Despite trying hard to find other uses for the facilities that would properly make use of their capabilities, the Department of National Defence was in haste to wash their hands of the relatively minor maintenance costs of mothballing them (especially the main bunker in Carp – the Diefenbunker) and pressured EPC to abandon the program ASAP after the ‘end’ of the Cold War. (In my humble view as a senior emergency planning official we ‘threw the baby out with the bathwater’ when we closed and disposed of the EGFs and stopped related planning). In 2001 it became clear (to me anyway) that that doing so was a mistake. Who knows what current arrangements exist to serve the same purposes as did the CoG program (if any) and how effective they would be in a nuclear-type terrorist crisis compared to the extensive and expensive-to-build original EGFs along with their associated activation plans. One can only hope!

BLOG # 3 – 14 Feb 2020

Speach Given on the Occasion of the Official Dedication of the “Diefenbunker” as a National Historic Site – June 27th, 1998

Good Afternoon Ladies and Gentlemen

I’m Dave Peters. I’ve been asked to say a few words about the war emergency purposes of the Diefenbunker, and to give you an idea of the activities took place there on a day to day basis. From 1982 to l997 I was a federal public servant with Emergency Preparedness Canada. EPC was the successor to the Canada Emergency Measures Organization, and the old Civil Defence Program. One of my duties was the management of the Continuity of Government Program. This place – Canadian Forces Station Carp or the Central Emergency Government Headquarters or the Diefenbunker as it was variously referred to, was an integral part of that program until about 1992.

The purpose of the Continuity of Government Program and the various bunkers that were part of the program was, and probably still is, widely misunderstood. One perception was that it would have provided a refuge for politicians and their families in a nuclear war. Another had it being some sort of Arc, a source of breeding stock for restoring the human species after a nuclear holocaust! The reality was of course quite different. It was to provide a fallout proof and in the case of this particular structure, blast resistant temporary safe location for a small number of federal and in the regions, provincial elected officials and their support staff. It was for those who had direct survival-of-the-nation responsibilities- and by the way without their families.

The aim was to ensure that there would be at least a thin thread of continuity of legally constituted Canadian government from before, to after a nuclear attack on North America. It was in places such as this that the situation would have been assessed and life and death decisions made affecting the survival of Canadians. The Diefenbunker was the flagship of the hierarchy of protected facilities and would have been the place from which central leadership would have been provided to the nation.

During its over three decades of existence this structure housed, on an ongoing, day-to-day basis, very important strategic telecommunications systems vital to the operational capability of the Canadian Forces. Over a hundred Canadian Forces women and men worked at CFS Carp. Their job was to operate the highly sophisticated equipment needed to provide this communications backbone. A small group of civilians supported that work, many of them local residents, and some of whom spent their entire career in the operation and maintenance of this facility.

Meanwhile some of us in Emergency Preparedness Canada and its predecessor, Canada EMO did our best to maintain the operational readiness of the various underground bunkers across the country. I say “did our best” because as the intensity of the Cold War ebbed and flowed over the years and the possibility of a nuclear attack on North America rose and fell with it, the resources to do the job varied as well. Nevertheless between the Department of National Defence, EPC and a few other departments and agencies, most of these protected facilities were kept at a reasonably good degree of preparedness for possible activation during the greater part of the program’s 30 years. As the location of the Central Emergency Government Headquarters, the Diefenbunker was maintained at a higher state of readiness than the rest.

As the federal government’s temporary war headquarters the Diefenbunker was part of a wide spectrum of government plans and programs designed to help as many Canadians as possible survive a nuclear attack. Included were evacuation plans, home and community fallout shelter programs, a system of emergency hospitals, medical stores and treatment centres, a comprehensive system of warning and informing mechanisms including the network of alerting sirens and emergency broadcasting stations, as well as an array of public information publications and pre-recorded announcements that were kept ready for use – just in case. Policy and implementation concerning these and other response and recovery actions, plus a wide range of other related civil departmental and military decisions would have been coordinated from the Diefenbunker.

By virtue of its day to day operational role and the special telecommunications equipment in the bunker, the military personal of CFS Carp stood ready to support the government by providing a network of highly survivable communications within Canada and to our allies in North America and in Europe.

From time to time emergency preparedness officials and staff of many federal government departments and agencies held exercises where we practiced getting ready and responding to what we all knew was the unthinkable and hoped was the impossible. But it was one of our jobs and we tried to do it well.

While in my own mind I have always been convinced that, short of a nuclear winter situation occurring, many people would have survived and human kind would have continued. Millions would have died immediately and later untold millions would have suffered death and illness. Civilization would have staggered and reeled from the blows of nuclear attack and the deadly radioactive fallout that would have at least temporarily contaminated large parts of the land. Nothing would have ever have been the same again! But the instinct for survival would have carried us through – if and it is a very big if – that nuclear winter scenario did not take place.

Having some form of continuous government to plan and coordinate alerting, take cover, evacuation, rescue and recovery operations and to provide for at least minimal continuity of essential services would have surely enhanced the ongoing survival chances of those Canadians alive after the attack. That was the hope! That was the expectation!

But fortunately for us all, all of these preparations never had to be tested. A miracle occurred— the Cold War ended….and not with a bang! Very few foresaw it taking place the way it did but it actually happened.

We will never really know how close we came to Armageddon. But we should ensure that this period in Canada’s and the World’s history is not forgotten and thus repeated at some time in the future. This then is the purpose of the Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum.

Thank you for joining us and I hope that you will encourage your families, friends and neighbours to come and visit and with us learn about this precarious era in our national and the world’s history.

(Dave Peters, was formerly an official with Emergency Preparedness Canada and for many years the senior official responsible for the civil readiness of Canada’s Emergency Government HQs )

BLOG #2 – 22 Jan 2020

Bed Spaces, Hot Bedding & Much More in the Central Emergency Government HQ (the ‘Diefenbunker’)

Over the years since the creation of the Museum in 1997 there have been discussions, usually between volunteers about the subject of ‘hot bedding’ in the bunker. As often happens when such a seemingly simple question is posed, a simple answer given without context is not appropriate (besides having only thin educational value!).

First let me say that definitive procedures for activating, occupying and operating the Central Emergency Government HQ (the ‘bunker’) were sadly lacking when I took over the Emergency Government Facilities readiness responsibility in 1983. My predecessor in the Director, Emergency Operations Coordination (DEOC) position (the late Armand Wigglesworth) had done his best to be properly ‘ready’,given the complete absence of governmental/senior management support in the late 60s through the 70s. Many of the ‘Acco-fastener bound’ documents that we have in our archives were originally created by him, although I had more up-to-date versions and additional procedures written later on in the 80s. I was ‘lucky’ to have a boss who was interested and of course events resulting from the rising Soviet nuclear threat and its invasion of Afghanistan along with US President Regan’s rearmament/’Star Wars’ programs meant that I got significant support in rejuvenating the Continuity of Government Program during my tenure in EPC.

Thus in 1984 an interdepartmental committee was formed (under my chairmanship) to ensure that at least the central facility could be made operational quickly if need be. This CEGHQ Activation Committee met every six to eight weeks and made significant progress in such preparations over the next six years until the Cold War ended and eliminated (at least for now) the need for such a program. We updated procedures, removed the military from the civilian areas of the facility, got some departments to seriously prepare their rooms, reactivated the Essential Record Program, renovated the EmGovSitCen, renewed our contacts with the equivalent US facility (Mt. Weather, VA), modernised the furniture and some of the equipment in the civilian areas of the facility, created an officials CoG briefing video (Just In Case), got the military to relocate the FWC back to Carp, and held two-day overnight exercises every December to practice operating procedures.

All of the above to say that from the outset in 1962 or so there was not a great deal written down in a doctrinal sense (at least that I could find). The best that we can do is refer to those of us that were around for different parts of the three decades of the bunker’s operational existence, complimented by research into what documentation we have in our archives and what we may be able to dig up from other sources such as DND’s Directorate of Heritage and History and the National Archives. I know we kept detailed minutes of the Activation Committee’s meetings. They are probably archived in government files somewhere where they will never see the light of day!

So here is what I recall about the usage of the bunker’s bed spaces:

I don’t know how many females would have been assigned to the bunker in the 60s but at that time there was an area – including washrooms – set aside (back part of the 300 level) for their use. Later, in the 1980s we did not bother to try to keep track of or make any particular bed spaces allowance for the gender of those assigned to bunker duties. Such issues would have been sorted out after lock-down as needed.

While the total number of bunker-assigned staff was initialyl (1960s) probably in the 400s, during my time the bunks in the anti-rooms of the bed rooms were counted on for use in the total numbers of bed spaces needed to accommodate about 535 souls that then (80s)would have been assigned to duties in the bunker. Remember that most of the non-senior officer military positions at the bunker were to be accommodated on a hot-bed basis. This would have included female members of the forces as well. None (or very few anyway) of the male or female civilian occupants of the bunker were expected to hot-bed. With the passage of the Emergency Preparedness Act in the late 80s this would have had to eventually change. That was because the 1988 Act called for protection of ‘constitutional’ government.

Prior to that time protective arrangements referred to government, not ‘constitutional’ government. The former can be dealt with by the ‘executive’ (War Cabinet working with the Governor General). The latter requires having a quorum of both the H of C and the Senate and the Supreme and Federal Courts. After consulting with constitutional legal experts it was decided that having 60 to 100 more (than the 535) bed spaces would do it. We were in the process of triple bunking many of the double-bunked bedrooms to meet these increased needs when the Cold War suddenly ended.

The number of Cabinet Ministers that would have been at the bunker varied but we counted on between 13 and 18, to cover the following: Agriculture; Finance; Public Works; Communications; Employment and Immigration; Energy, Mines & Resources; Environment; External Affairs; Fisheries & Oceans; Industry, Trade & Commerce; Labour; Health & Welfare; Post Office; Solicitor General; Transport Canada; Supply & Services; Justice; National Defence; Emergency Preparedness; CMHC.

The absolute minimum we needed was four. Those, in addition to the GG, were sufficient to form the Governor-in-Council , and executive body and to pass regulations by decree – prior to the ‘constitutional issue that I mentioned above changing things. They would have had priority use of the individual bed rooms on the 200 level, but there would have very likely been sufficient single rooms for the ED of the CBC/Radio Canada, the Commissioners of the RCMP and the Coast Guard and like positions.

In my time (1980s and early 90s) the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) appeared to be the driving force/largest user of the OSAX. There was a close relationship between the bunker staff and CSE. There was a metal plaque that they donated to the museum in the late 1990s. It should be in the museum’s collection somewhere. I don’t know whether or not the CO was permitted entry to OSAX. I somehow think he was since it was his personnel that operated it. I was not allowed entry as I had no ‘need to know’, a key component in all security clearance procedures.

BLOG # 1 – 20 Jan 2020

The Bikini and the First Bomb Tests

Garments similar to the bikini have been worn for ages. Paintings from ancient Italy prove that women were wearing revealing two-piece outfits at least four thousand years ago. But the modern bikini was born in 1946, and was called the ‘bikini” for a specific reason.

In July 1946, the U.S. government announced that they would soon be testing an atom bomb at the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in the North Pacific. This was the first time the U.S. government announced the testing of an atom bomb, and people around the world were worried about the military exploding the most powerful bomb in history,

End-of-the-world fears were running high. Only the ‘any-excuse-for-a party” French took the whole thing in stride: They held “Bikini” parties, determined that if the world was about to be blown up, they were going to go out – quite literally – having a blast.

At the same time, Paris was hosting a fashion show that was scheduled to take place four days after the explosion. Designer Louis Reard had already planned on introducing something explosive himself- He was putting model Micheline Bernardini in a skimpy, two piece bathing suit. He decided that if he called it a “bikini,” he’d attract even more attention.

The organizers loved it. They figured that if the world ended, no one would be around to complain about how much skin the model had revealed, and if the world didn’t end, they might just have introduced something new in beachwear.

The world survived. And so did the bikini. Bikini Atol and its former occupants are however a bit worse-for-wear!

(From “I Wish I’d Thought of That” Globe Communications Group, Boca Raton -FL 1998)